Even from a distance of some miles the Fastnet Rock looks stark, haunting.

As you get closer it projects a power and strength that can resist an ocean. But you wouldn’t want to be part of that resistance.

Leave that to the rock and the lighthouse that reaches into the sky from its craggy base. The Fastnet Rock is the most southerly tip of Irish terrestrial territory. In the days when passenger liners ferried immigrants to the New World it was known as “Ireland’s Teardrop.”

It would be the last piece of Ireland that countless hopeful souls would see from the decks of their ships as they turned westward into the wide Atlantic. The Titanic would have sailed close by “The Fastnet.”

Closing in. Irish Echo photo

On a day in August last year that would have passed for benign for these waters a group of us, family and friends, set out from the West Cork village of Baltimore for a close up look at the fabled rock and its iconic lighthouse. This would be a two stage journey.

Stage one was a ferry ride out of Baltimore, past Sherkin Island and on to Clear Island and its welcoming harbor.

Stage two would be from Clear to the Fastnet, but now on a larger ferry that had arrived in Clear from Schull.

This boat had made the journey across a stretch of water with the names “Long Island Bay” and "Roaring Water Bay.”

These watery tracts are exposed to the Atlantic and, on certain days, the term “bay” hardly seems to apply. And, on more than a few days in any given year, it most certainly does not apply to the waters around Fastnet Rock.

On this day, however, the sea, though lively enough, is just that. And so we cross the miles from Clear Island to Fastnet Rock with a fresh breeze and a little spray in our faces. This was not the cast in the middle of August, 1979.

The Fastnet Race takes place every two years. The 2025 race, completed just a few days ago, marked one hundred years of a contest that now attracts over 400 assorted sailing vessels that take on a course of over 600 nautical miles.

Up close but close enough. Irish Echo photo

The race starts on the south coast of England with competitors sailing west for the Fastnet.

Once the Fastnet is rounded the boats sail back eastward for the finish which, in most recent years, is in Cherbourg, France. Sounds simple enough.

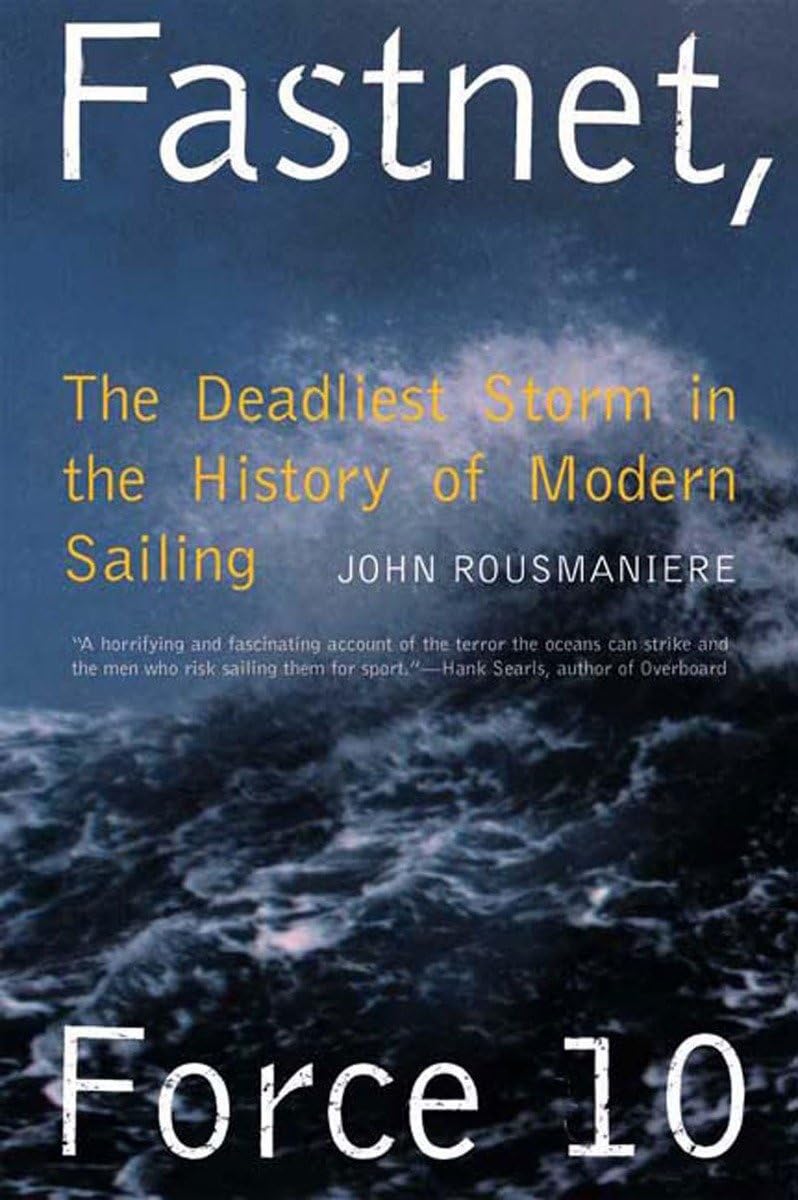

In 1979 the simple was overwhelmed by the complexity of a storm that, in terms of its unexpected intensity, pretty much came out of nowhere.

The race that year began on August 11 with 303 yachts competing in what was the climax of the five-race Admiral’s Cup series.

By August 13-14 the racing fleet, its skippers and crews, were facing into a rapidly intensifying storm in the Celtic Sea.

Expected rough weather morphed into hurricane force winds and waves as high as fifty feet.

To make matters worse, those waves were running in cross directions. It was a chaotic maelstrom.

Seventy five boats capsized, five sank outright.

There were 21 fatalities. As the calls for help crammed the radio waves the biggest peacetime rescue operation in that part of the world got underway.

Three navies, British, Irish and Dutch, would take part. Aircraft and lifeboats from England, Wales and Ireland would take to the air and water.

Among the lifeboats would be those from Baltimore and Courtmacsherry in County Cork. There was heroism in those frightening hours to match the fearful weather.

On our voyage to the Fastnet heroism, thankfully, was not required. Just reasonably adapted sea legs. The Fastnet Rock and its lighthouse is not a living thing.

But it radiates a presence that feels as if it is much more than rock, stone and concrete.

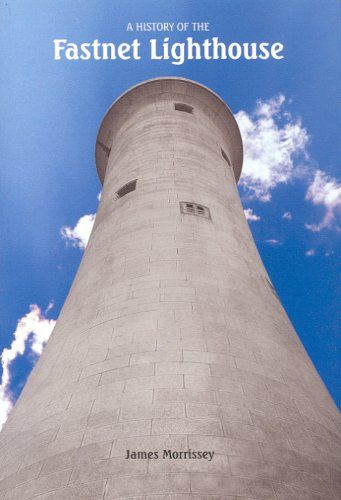

These days the lighthouse is automatic.

Farewell. Irish Echo photo

The onetime four member crew is no more.

The present day lighthouse is the second one to stand on the rock, the first, dating back to the 1850s, having been judged not up to its task in weather that, in one instance, unleashed a wave that smashed the glass in the light housing.

Construction of the current lighthouse began in 1897 and was completed in 1904.

The earlier lighthouse was a brick and iron construction. The current one is of Cornish granite.

It stands 177 feet high with a light that can be seen from as far away as 27 miles. In 1985 it was struck by a rogue wave measured at an astonishing 157 feet.

Thankfully, there were no such waves as our ferry rolled up to within yards of the rock. That said, the waves striking the base of the rock were big enough. It’s not a good idea to get too close.

All on board were treated to a history talk as the ferry rounded the rock at a pace allowing for plenty of photos and videos, and a lot of oohs and wows.

This is one scary, spectacular dot of terra firma on the edge of an ocean that can be merciful and merciless. We tarry for a while before turning around and heading back for safe harbor, the Fastnet Rock and its famed lighthouse in our wake and now, too, in our collective memory.

About the authors John Rousmaniere is an American author of numerous books on sailing. His “Fastnet, Force 10” is a definitive account of the 1979 Fastnet disaster. James Morrissey’s “A History of the Fastnet Lighthouse” is a critically acclaimed telling of the story behind this iconic oceanic beacon. Both books are available on Amazon.