Each year Mam reared about 80 turkeys for the Christmas market and to give as gifts. The birds she sold produced a little wave of money that would float our holiday extravagances, such as a bag of coal for the fireplace and a toy for each child. The parish priest and the nuns in Mountmellick, Granny, our aunt Teresa in Dublin, our aunt Kit in England, and several others received turkeys, while friends and men who had worked for Dad during the year got a pair of chickens or a duck.

Each December, Dad and his helpers gathered the birds not destined to be gifts, tied their legs together, loaded them into the horse’s cart, and brought them to the market in the town square. About 10 days before Christmas, Dad killed all the gift turkeys. First, he folded the wings and put the bird between his knees. One year when I was about 10, I was assigned to hold the bird’s legs projecting behind Dad to keep them still. Dad grasped the turkey’s head, bent up the neck, and cut across it with the broken kitchen knife he had sharpened on the wall of the sandstone trough. The pain and struggles of the bird went into its legs and then up my arms and into my chest. Later, when I asked Dad not to ask me do that job anymore, I was surprised when he said yes; I had been afraid he would tell me to be a man.

When the turkeys had experienced the one bad day in their otherwise happy lives, they were hung upside down on iron spikes high in the dairy walls. During the week they were there, it was only my fear of disobeying Dad that forced me into the dairy, my half-hooded eyes avoiding the slit throats and purple heads.

The turkeys were plucked at night in the pallid yellow light of the double-wicked paraffin-oil lamp hanging on the whitewashed kitchen wall. Dad and Mam and Uncle Jack plucked, each sitting on a straight-backed kitchen chair, each with a soft beet-pulp sack across their knees and a dead bird in their lap, the head hanging down and almost touching the floor, eyes closed. The sound of the feathers being ripped out was like the sound of a page of paper being torn from top to bottom. Sometimes one of the pluckers made a “tsk,” meaning they had scarred the bird’s skin.

The pluckers always left the wing feathers on because the person getting the turkey might dry the wings to use them to sweep crumbs of turf and ashes into the ash pit.

Once while plucking, shy Uncle Jack said out of the blue, ‘“Gussie McFlynn rod a hin from here to Ballyfin. When he came back, he made a crack and blew the feathers off her back.”

As the adults worked, movement in the kitchen was restricted because the breezy wakes of passing children swirled the plucked feathers up into the air, causing them to be breathed into nostrils and set off sneezing fits. And when a feather landed on the open fire, it hissed and made a foul smell like hair burning. Sometimes the flames of the oil lamp on the wall leaped up and devoured a feather that had floated across the top of its glass globe.

Dad was the one who pulled out the pinfeathers of all the birds with pliers. He was the one who tied the feet of the naked birds together and hung them upside down again on the nails in the walls in the dairy. He also kept Mam and Uncle Jack supplied with dead birds. Dad was a great organizer. Mam once said, “If the Irish army marched into our farmyard, Dad would assign a job to each soldier as he passed by.”

On the morning after the plucking, all the feathers were gone from the kitchen. Mam spent the day preparing the turkeys that would go to the Post Office. She did not cut off the feet, wings, or head, nor did she draw them. “They travel better with their guts in,” she said. Mam folded the wings, the neck, and the feet against the body and tied them with white twine. She weighed the bird on the spring scales hanging on the wall, said a number to herself, and wrote it on a label. Next, she wrapped the bird in butter paper and tied it in place with twine; she did the same with a sheet of brown paper; then, with needle and thread, she sewed the whole thing into a piece of an Odlum’s flour sack. The turkey looked like a lumpy football in a tight sock with its end sewed up. “That’s the way the Post Office says to do it,” Mam said. Then she wrote an address and the weight of the contents on the label.

When Mam had all the turkeys ready, Dad caught the black pony, yoked her to the trap, and carried out the parcels. Turkey season was over for Mam, except for preparing a bird for our Christmas dinner. On Christmas morning she spread live turf coals on the hearth, placed the lidded cast-iron baker holding the turkey on them, and then surrounded the baker with more glowing coals.

Our beautiful, brown Christmas turkey marked the high point of our culinary year.

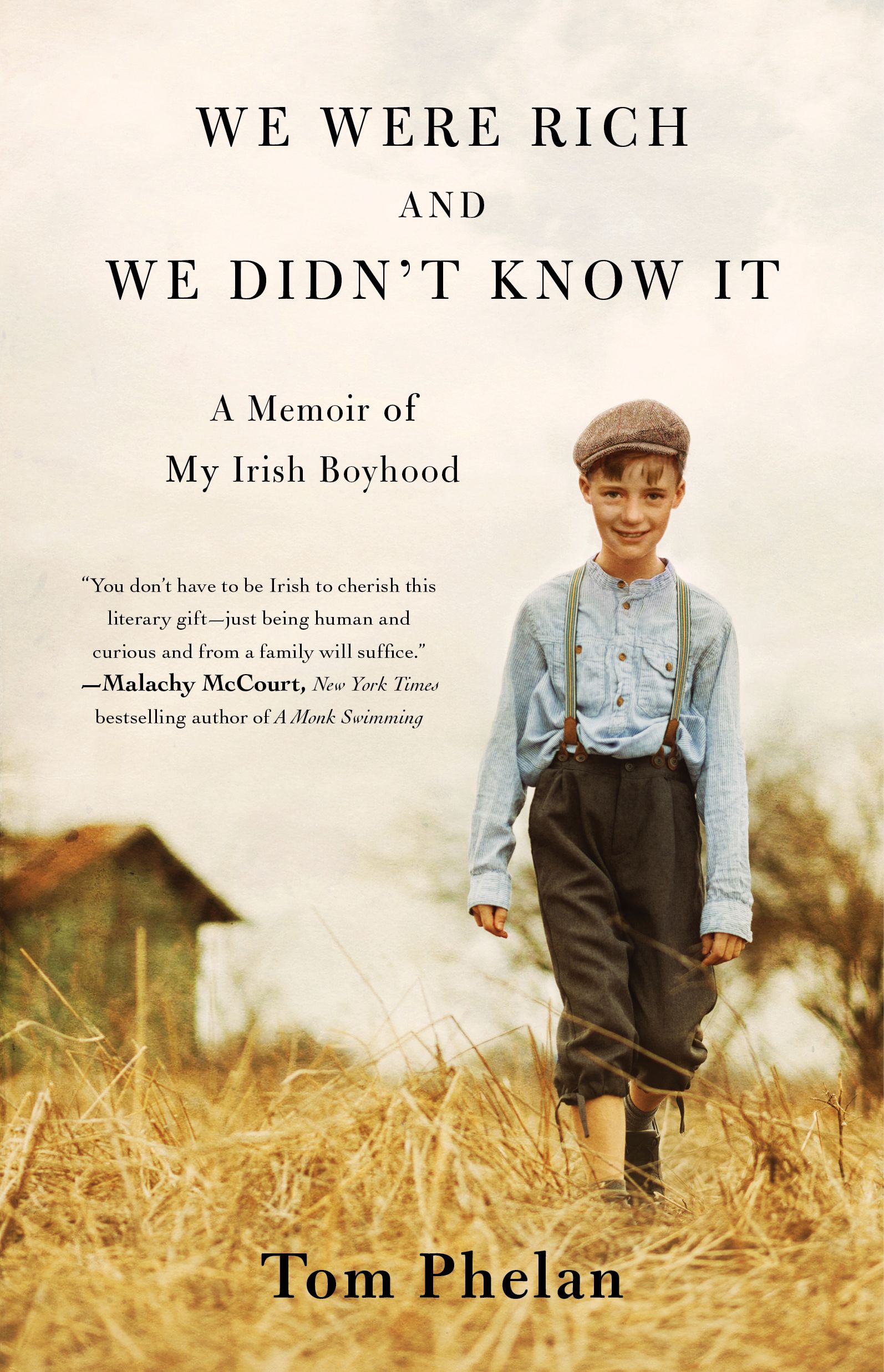

Excerpted from “We Were Rich and We Didn’t Know It: A Memoir of My Irish Boyhood” by Tom Phelan. © 2018 by Glanvil Enterprises, Ltd. Published by Gallery Books, a division of Simon and Schuster. You can read more about the author at at his website here.