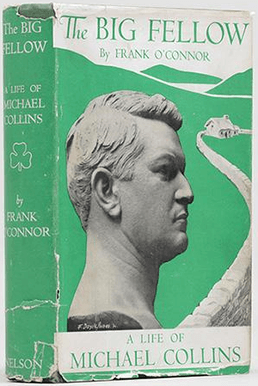

"This book has been a labor of love. To some extent it has been an act of reparation,” wrote Frank O’Connor in the foreword of a book of his in 1937. “Since the fever of the Civil War has died down, I have found myself becoming more and more attracted by Collins as a character.”

We’ve been featuring here articles about that conflict of 100 years ago, sometimes with special emphasis on the big personalities – such as Cathal Brugha, a couple of weeks back via Daithi O Corrain and Gerard Hanley’s excellent study. Upcoming are pieces on Eamonn Duggan, Erskine Childers, Joe McKelvey and Ernie O’Malley.

Michael Collins, the subject of “The Big Fellow” is, of course, one the biggest personalities of them all, with really only Eamon de Valera challenging him for equal consideration. But O’Connor himself was an unknown soldier in 1922-23 under his real name Michael O’Donovan – one of 13,000 people imprisoned by the Irish government during the Civil War. International literary stardom lay ahead of him.

His 1931 short story “Guests of the Nation” drew on his late teenage years in the War of Independence, but he, like his friend the fellow Cork writer and ex-anti-Treaty militant Sean O’Faolain, got established also by writing biographical studies; the latter produced books on Daniel O’Connell, Countess Markievicz and Wolfe Tone.

O’Faolain had started on a serialized project on Collins, but keeper of the flame and author of a 900-page two-volume biography Piaras Beaslai blocked it with a suit for plagiarism.

With regard to “The Big Fellow,” author of “Mick: The Real Michael Collins” (2006) the late Peter Hart said, “Beaslai approved, although a franker revised edition issued in 1965 angered some old comrades.”

Wrote Hart of the O’Connor biography, “Based on interviews with former comrades of Collins, it is a masterpiece of efficient and evocative writing—the finest portrait that had appeared so far.”

The 1937 book’s “Acknowledgements” was quite the who’s who of the revolution, particularly on the pro-Treaty side, but included his friend and fellow combatant Ernie O’Malley and others who were anti-Treaty. Among the works consulted, according to the foreword, were Dorothy Macardle’s anti-Treaty and pro-de Valera “The Irish Republic” (he thanked her for allowing him see the proofs before publication) and “Peace by Ordeal,” a study of the Treaty negotiations by Frank Pakenham (later Lord Longford and a sympathetic biographer of de Valera).

He added only two works to the list for the 1965 edition: Rex Taylor’s 1958 biography “Michael Collins,” the only one to appear in the years since, and O’Malley’s “On Another Man’s Wound”; “but I’ve preferred not to rewrite,” he said.

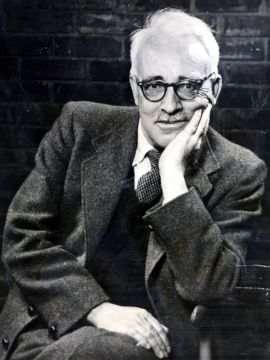

Frank O'Connor in the 1960s.

In the 2016 collection of essays “Modern Ireland and Revolution: Ernie O’Malley in Context” (edited by Cormac O’Malley), contributor Nathan Wallace writes that O’Connor “came to recognize Collins’s principled leadership of the Free State as the political corollary of his own mature literary principles.”

O’Connor has a report of Collins in London after the Treaty had been signed asking one of the young officers of the Southern Divisions, “What do you think of it?”

“It won’t do for Cork,” came the reply.

O’Connor described the reaction, “Collins growled, the smile withering from this face. At such a time Cork must have loomed very great in his mind.”

He continued, “The objectors were still few, but they were vociferous – lads of 19 and 20 [he himself turned 19 in September 1922], grown men with inward-looking eyes of a Terence MacSwiney, women whose sons or brothers had been killed.”

Before too long, De Valera’s “rejection had given new justification to the objectors; the Treaty was no longer a matter of disagreement, it was a test of orthodoxy.”

The transformation of O'Connor's position over the previous decade can be seen most dramatically in “The Great Talk,” his chapter on the Treaty debates in the Dáil.

He objected to the leading opponent of the Treaty quoting the lost leader of the previous generation: “It is a pity that de Valera did not take the context because in fact Parnell said neither.”

Anti-Treaty hardliner Austin Stack was: “Collins’s one-time friend and now among his bitterest enemies. Dull, pompous, unutterably futile, the threadbare sentiments string themselves out.”

Collins’s own was a “good and manly speech” but no match for some of his allies’ contributions. He commended Arthur Griffith’s, for example, as “the crowning achievement of his life.”

Of another opponent, he said, “Childers, still worried—more deeply worried than ever, for it is not only that poor boy Collins who is going wrong but a whole country—delivers a prophetic speech which is remarkable because all of its prophecies have proven false.”

O’Connor added a few lines on, “It was followed by another prophetic speech, remarkable because all of its prophecies have come true; the first great speech of [Kevin] O’Higgins, still only an untried young politician.” (O’Connor wrote in the next chapter that Collins “had no power of abstract thought; perhaps O’Higgins was the only man among the revolutionary leaders who had.”)

In 1938, seven members of the Second Dáil, which had debated the Treaty, gave over “authority” of the Irish Republic to the IRA’s Army Council, which before too long was collaborating with the Nazis.

O’Connor set his sights on three of those TDs in his 1937 account: William Stockley, J.J. O’Kelly and, several times, Mary MacSwiney: “Professor Stockley’s speech shows a style like a sieve: the ideas he seeks to sustain sink gently down like fine sand through the hole in the syntax”; O’Kelly “takes occasion to point out that much of the disunion has been caused by speaking English and, breaking into English, proceeds to create more of it”; “Miss MacSwiney whose three hours’ flight of oratory, Mr. O’Kelly thought, put her ‘in the highest ranks of the greatest orators of our race’—interprets the situation far better. She makes it plain at least that the issue is rejection or civil war.”

O’Connor continued, “Then in a noble speech, Beaslai hit it off magnificently. He quoted Colum’s ‘the poor Irish nation striving to be born.’ He saw in the Dail ‘a body of small people, dry formalists and politicians, without imagination. We cannot rise to a great occasion. We haven’t the vision.’”

The reception for the book in America, where it was published as “Death in Dublin,” was generally mixed, according to Robert C. Evans in a survey in “Frank O’Connor,” a 2007 collection of essays edited by Hilary Lennon.

The magazine that would help make him famous, the New Yorker, was negative, but there were some glowing reviews. “Frank O’Connor is one of the small band of significant young Irish writers who are attempting to define the new Ireland to this generation,” said the New York Times’ Horace Reynolds, by “fighting to free the Irish intellect.”

Evans reports that Reynolds “praised O’Connor’s strong and sensitive fiction and asserted that O’Connor had now ‘written brilliantly’ of Collins.”

Irish émigré Michael Sayers (one of Katrina Goldstone’s quartet -- see here) wrote in the New Republic that O’Connor’s biography “sharpens the drama of a novel with the fidelity of a history…and the personality of Collins emerges starkly.”

In that 2007 collection of essays, Terence Brown writes that O’Connor, whose short story “Guests of the Nation” had already shown a “subversive indifference” to ideology, “registered his alienation from the Free State predominantly in socio-cultural terms. His voice was raised in protest against the narrow provincialism of the new order. As a former irregular of civil war days, his choosing to write a celebratory, fierce biography of Michael Collins was like a personal declaration of intellectual independence.”

Brown cites a 1983 biographer on this aspect of his career, James Matthews, who argues he’d become “Ireland’s most abrasive voice of conscience. He believed he was standing alone, fighting a sort of guerrilla war against the forces of stupidity and vested interest. To clarify the image of Collins, to support the novels of his friends, to decry the pillorying of a public figure on the stage of the national theatre, to defend an old storyteller and his wife against hoodlum priests, were all simply moral obligations of the artist in a provincial country.”