“It started first as an investigation into one Irish Jewish writer’s life and interests, and then became transformed into a fervent quest for a lost literary world,” says Katrina Goldstone in the introduction to her book “Irish Writers and the Thirties: Art, Exile and War.”

She recalls finding in the many files of the archive in the National Library of Ireland devoted to “Out She Goes: Dublin Street Rhymes" author Leslie Daiken (1912-1964) “two huge bottle-green leather scrapbooks of the kind a Dickensian book-keeper might enter outgoings in copperplate handwriting.”

The first Goldstone inspected was filled with materials relating to the field for which the poet, journalist, publicist, scholar, activist and writer became best known, though he was involved with many throughout his life -- "cuttings on children’s rhymes, articles on lullabies, reviews of books on the significance of play, reflections on the myriad customs and rituals of childhood through the ages.”

The second began with tourist features about Ireland, profiles of people in the Irish community in London and other work presumably done for payment. Then one-third of the way through that volume, Goldstone began to note older material that marked a shift in tone — “articles on ‘poet as social rebel,’ extracts from ‘mosquito’ left-wing literary magazines, trade union journals, these literary fragments interleaved with faded educational posters, promotional flyers for forgotten books, stark black-and-white woodcut illustrations of the unemployed.”

She adds in the introduction, “It soon became clear that Daiken’s significance was more in the collective than individual.”

Indeed, when his brother spoke with Goldstone in the 1990s, she was struck by how, even more than 30 years after Leslie’s death, the “lack of appreciation of his many cultural efforts on behalf of Irish writers still distressed Aubrey Yodaiken.”

But Goldstone’s immediate focus is a Daiken “circle” of exiles, comprising himself, Charles Donnelly (1914-1937), Ewart Milne (1903-1987) and Michael Sayers (1911-1910).

All made an immediate impact upon arriving in London, finding niches writing for leftist and mainstream literary publications, and three of them collaborated on their own mimeographed magazine, Irish Front.

However, while these four poets were anthologized up through the 1950s, their work went largely forgotten in subsequent decades. They never became part of the Irish canon; in the words of Milne in a letter in the 1970s, they never quite managed “to set the Liffey alight.”

They were, nonetheless, very much young men of their time as part of the Popular Front, the international left’s response in the mid to late 1930s to the rise of far-right militarism in Europe.

“They were thinking globally, interested in internationalism, supporting Republican Spain, opposing fascism and they linked in with amazingly diverse groups — English socialists, Irish republicans, artists, American radicals, Hollywood writers,” Goldstone told the Echo.

“They supported so many causes now forgotten such as the Free Tom Mooney campaign, for instance, the Irish American wrongly imprisoned for over 20 years. It is an academic cultural history but written accessibly, revealing how there were Irish writers trying to expose injustice and also find new ways to express ideas of solidarity at a time of great crisis with the rise of Hitler,” said the Dublin resident who combines historical research with communications consultancy for arts groups.

“Two of the four writers are Jewish and all four were outsiders to an extent in the Irish society of the day being leftwing at a time when that brought opprobrium, so it was also fascinating as to how they navigated the politics and their hybrid identities,” she said.

Added Goldstone, who was born in Belfast and raised there in the era of the Troubles, “I also have a chapter on how difficult it was for women to be heard or even published and yet they were endlessly inventive, and also very supportive of one another, writers and activists like Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, Rosamond Jacob and journalist Mairin Mitchell, who wrote about Spain on the eve of Civil War."

Of the four writers at the center of this “hidden cultural history,” Milne had the easiest time settling in as an exile in London. Born in Dublin to an Irish-Welsh mother and an English father, he was sometimes dismissed at home as an “Englishman.” A decade older than the others, he worked for years on boats and in factories before concentrating on his writing career.

Milne initially traveled across the Irish Sea to work with the Spanish Medical Aid Committee and eventually volunteered as a medical courier and ambulance driver during the Civil War in Spain.

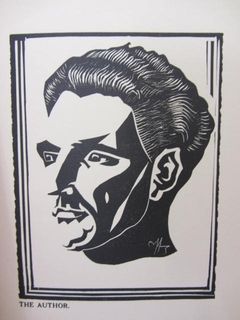

A portrait of Ewart Milne by Cecil F. Salkkeld, as it appears in Milne's book "Forty North Fifty West."

Leslie Herbert Yodaiken’s immigrant father made a living according to the 1911 Census as a “rubber merchant,” which suggests his scrap business specialized in bicycle tires. There was nothing in the family’s background that hinted at a history of Jewish radicalism, but the young renamed Daiken became active in the leftist Republican Congress (he used the pseudonym Ned, or N.E. Kiernan for pieces in the paper of the same name). He died suddenly in London after returning from a spell lecturing at the University of Ghana. He was 52.

Donnelly, who came from a middle-class Catholic family in Tyrone, was also a member of the Republican Congress. His widower father brought his large family of children south of the border in the late 1920s, and in Dublin the young poet was shocked by the poverty he saw in the city’s slums.

In London, Donnelly joined the International Brigades and was killed in the fighting in Spain at age 22. Although he had the shortest life of the four, he’s had the most written about him, says Goldstone, with novelist Joseph O’Connor’s 1992 biographical study, “Even the Olives are Bleeding,” being particularly notable in that regard.

Sayers, who lived 98 years, proved uncooperative when a potential biographer approached him. The son of a Lithuanian-born businessman, he grew up Jewish in Dublin, though in more comfortable circumstances than his childhood friend Daiken. His father was a committed Irish republican, who, family stories said, was an associate of and provided a safe house to Michael Collins during the War of Independence.

In London, the young writer counted George Orwell as a friend and T.S. Elliot a mentor. Sayers moved to the United States in 1936 where he wrote investigative articles about fifth columnists for a liberal newspaper and later a series for another about anti-Semitism in Ireland.

Sayers’s screenwriting career was hampered by his leftism, even though it was of a less than doctrinaire kind. Ultimately, he joined the merry band of blacklisted writers who worked on television’s “The Adventures of Robin Hood” — at least five episodes while using the name Michael Connor (an allusion perhaps to the underground leader his father was supposed to have hidden).

Writer and emeritus professor of English at Georgetown University George O’Brien said in the Dublin Review of Books that “Goldstone’s ‘Irish witnesses to global events’ are illuminating and instructive not only for their principles and actions but also for the more vivid light in which they show the country, or at least Dublin, in the Thirties.”

And “Irish Writers and the Thirties,” O’Brien continued, is, “thanks in large part to its untiring research, its copious bibliography and its commitment to opening and broadening awareness of the diverse world of Irish letters, a valuable study.”

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

A warm room! – When I was finishing the book I was very disciplined, and started at 8 a.m., and worked through the day. I am now a morning person and try and get writing done early, before other tasks or work. It’s easy to be distracted but sometimes just gritting the teeth and staying at the computer is what it takes.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Stick at it. I first thought of writing a book on Irish Jewish writer Leslie Daiken, over 10 years ago, and I had first come across Daiken’s story in the 1990s. Sometimes the seeds of ideas and inspiration percolate for decades!

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

“The Vanishing Half,” by Brit Bennett; “Family Lexicon,” by Natalia Ginzburg; “The Search Warrant” by Patrick Modiano.

What book are you currently reading?

“Square Haunting Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars,” by Francesca Wade.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

Too many – but Cary Nelson’s “Revolutionary Memory “and Jan Montefiore’s “Men and Women Writers of the 1930s: The Dangerous Flood of History” are books I was inspired by and come back to.

Name a book that you were pleasantly surprised by.

“Vauxhall,” by my friend Gabriel Gbadamosi, a story of growing up in an Irish Nigerian household in London in the 1970s, its lyrical, sad, wise and funny, in some sections reads more like poetry. The stories of Irish Nigerian families in England and in Ireland are quite neglected in Irish diaspora histories or fiction

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

Toni Morrison.

What book changed your life?

Angela’s Davis’s “My Autobiography,” in the 1980s. I stumbled into a tiny bookshop called L’Harmattan in Paris which specialized in the literature of Francophone Africa, and it was like entering a new world, they also had a section on African-American fiction and non-fiction where Those books and others by writers such as Ousmane Sembene, Aime Cesaire, Frantz Fanon, all of which I found browsing the shelves of L’Harmattan. In their own ways sowed the seeds for my curiosity about art, protest and literature and how writers respond to crisis.

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

Westport, the feeling of looking out over Clew Bay, browsing in the bookshops and eating fish and chips outside in bracing sea air is bliss. And if the sun shines, a little bit heavenly.

You're Irish if…

you talk about the weather constantly, in particular, rain!

For details of Thursday's Glucksman Ireland House event, click here.