California has long been home to the eccentric and free spirits, so naturally the highly eccentric Irish mystic, poet and Celtic mythologist Ella Young was drawn there. The first woman to hold an endowed lectureship in the English Department at the University of California at Berkeley, Young left several enduring legacies on the Golden State’s literature, counterculture, and environmental movement.

Young lived the first 58 years of her life in her native land, but even before leaving for America, she’d traveled far from her conservative Ulster roots. Born in December 1867, in Fenagh, a townland near Ballymena, Co. Antrim. Ella was eldest of five daughters of a Reformed Presbyterian minister. The family moved to Dublin during her childhood and Young graduated with a BA in history, political economy, and law from the Royal University of Ireland. Abandoning Christianity, Ella’s interest in the spirit world led her to join the Hermetic Society, the Dublin branch of the Theosophical Society, which sought to awaken the power and presence of Ireland’s ancient spirits. Young was greatly influenced by fellow Ulster mystical poet George William Russell, aka AE, and she soon became one of his select group of protégés known as the "singing birds.”

She found her muse and published her first volume of verse in 1906, and her first work of Irish folklore, “The Coming of Lugh,” appeared in 1909. Young mixed with luminaries of the Celtic revival including J.M. Synge, W.B. Yeats, and Maud Gonne, with whom she might have had a romantic relationship. Like other writers of her day, Ella found great spiritual riches in the West of Ireland, where Irish was still the spoken language of the locals and where she was also able to hear what she called the Music of the Faerie, the ceol sídhe.

Ella completed a master’s degree at Trinity, but she would be drawn into the revolutionary fervor then sweeping Ireland. Young’s immersion in Celtic mythology and theosophy led her to promote a spiritually inflected Irish nationalism. A friend of Patrick Pearse, Ella became a member of Sinn Fein in 1912 and a founding member of Cumann na mBan in 1914. Ella witnessed the 1916 Rising in Dublin and is alleged to have hidden ammunition under the floorboards of her home and helped two escaped republican prisoners to leave Dublin. She strongly opposed the Treaty signed on Dec. 6, 1921. Her mentor Æ backed it and the pair never spoke again. Young was interned by the Free State in Mountjoy prison and in the North Dublin Union during the subsequent Civil War.

An ardent cultural nationalist, Young believed the revitalization of Irish culture should be realized through a reconnection with its Celtic mythological roots. Young taught in Dublin, but her gender, politics and Protestant background severely limited her career opportunities and so she left Ireland for the U.S. in the mid-1920s, where she was to spend the rest of her life. Her emigration, she claimed, had been foretold in 1914 by a Romani fortune teller.

Fortunately for Young, Celtic studies scholar William Whittingham Lyman Jr. left his Berkley lectureship in 1922 and she was hired to fill the vacancy in 1924. Ella, however, was almost forbidden entry into the United States. During an interview at Ellis Island, Young was detained as a probable mental case when the authorities learned that she believed in the existence of fairies, elves, and pixies. However, outrage by her American readers at the ban helped her finally gain entry.

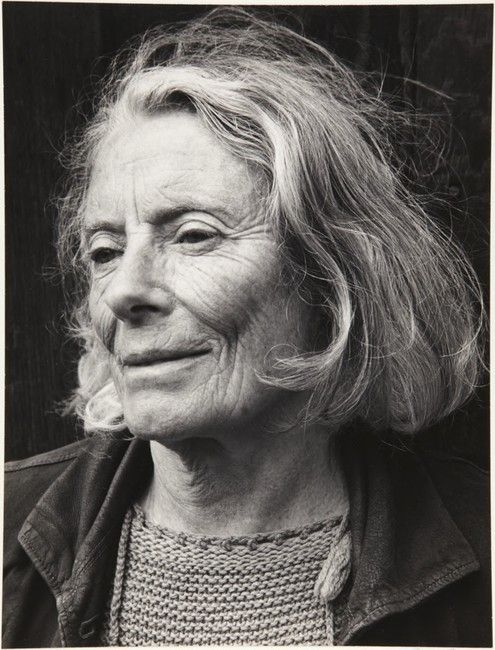

Young fell in love with Berkeley and Berkeley loved her back. She adored the college town, especially its exotic flora, breathtaking views, and its student culture. Ella quickly inspired a cult-like following in California. A striking woman, she cut a dramatic figure with a noble forehead and face that seemed to shine with an inner light. She lectured in what she considered the traditional purple robes of a Druid bard, which she called her “reciting robes,” to visually portray an authentic Irish identity. She let her shoulder-length silver hair hang free and instead of shaking hands when introduced, she raised her hands high in the ancient druid greeting. Poet Padraic Colum compared her to the ancient “women who knew the sacred places and their traditions, who knew the incantations and the cycles of stories about the Divine Powers, and who could relate them with authority and interpret them wisely. . . She speaks of Celtic times as if she were recalling them.” A gifted speaker, Ella held her listeners spellbound with the heroic myths and sagas told in her lilting Irish voice – the voice of the bard, a keeper of the ancient teachings of her ancestors.

Young was, above all, a gifted storyteller and children’s author. She published “The wonder-smith and his son” (1925), “The tangle-coated horse” (1929), and “The unicorn with silver shoes” (1932); stories for children, inspired by themes from Celtic myth, with beautiful illustrations and written in her delicate, carefully cadenced prose. “The unicorn with silver shoes” was nominated for the American Newbery prize for children's literature in 1932; all her children's stories were repeatedly reprinted until the 1990s.

Young was a frequent guest at the home of the celebrated California poet Robinson Jeffers, who was also deeply influenced by the Celtic revival. Jeffers and Young both identified the physical and spiritual similarities between California’s Big Sur and the West of Ireland. Ella considered dramatic Point Lobos in Marin County, where she communed with the dryads of the pine trees, the sea spirits, and the great guardian Deva who hovered over the sea with shining wings, to be the center of psychic power for the entire Pacific Coast. Young also became a close friend of Virginia and Ansel Adams, the latter the renowned photographer of California’s wilderness, who made Yosemite Valley a symbol of the state. Adams took several dramatic portraits of Young in her “reciting robes.”

Young lectured that an awareness of the supernatural world in Celtic folklore and literature could bring her listeners into a closer relationship with the natural world around them. Her love for the beauty of California made her an environmentalist long before it became fashionable, and also she saw the earth as a great living being. She forged a close friendship with Dorothy Erskine, an early California environmentalist and advocate for limiting growth. Young also founded The Fellowship of Shasta, which became involved in environmental activism, working successfully to prevent developers from building on Point Lobos and also with the Save the Redwoods League, which preserved the remaining old-growth forests of California.

An enemy of materialism and egotism, Young espoused “the natural world and our relationship to it” as an alternative to consumerism. Ella moved to a Theosophic commune in Oceano, near San Luis Obispo in the early 1930s, and became part of a community of artists and writers living on the sand dunes, known as the Dunites. Thanks to her friendship with Ansel Adams, Ella stayed with the community of artists in Taos, New Mexico, where she met Georgia O'Keeffe and Frieda Lawrence, and studied Native American and Mexican myths.

Back in California, Young assembled around herself a fascinating circle of artists, writers and free thinkers. She became close friends with the Irish-born landscape painter John O’Shea and other West Coast painters. Young also became intimate with composer Harry Partch, who set several of her poems to music. Perhaps a lesbian herself, Young befriended California pioneers of sexual liberation, such as Elsa Gidlow, the British-born lesbian poet, and Gavin Arthur, a bisexual astrologer and sexologist whom Young first met in 1920s Dublin.

In the last year of her life, she claimed that she had been in communication with the occupants of a thimble-sized spaceship which came and hovered in her garden. Ella died of cancer in her cottage on July 23, 1956, at the age of 88. She was cremated, and her ashes were scattered in a redwood grove. She left the royalties from her books to a society that protected those redwoods.

[The photograph of Ella Young was taken by Ansel Adams in Oceano, Calif.

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust / Princeton University Art Museum]