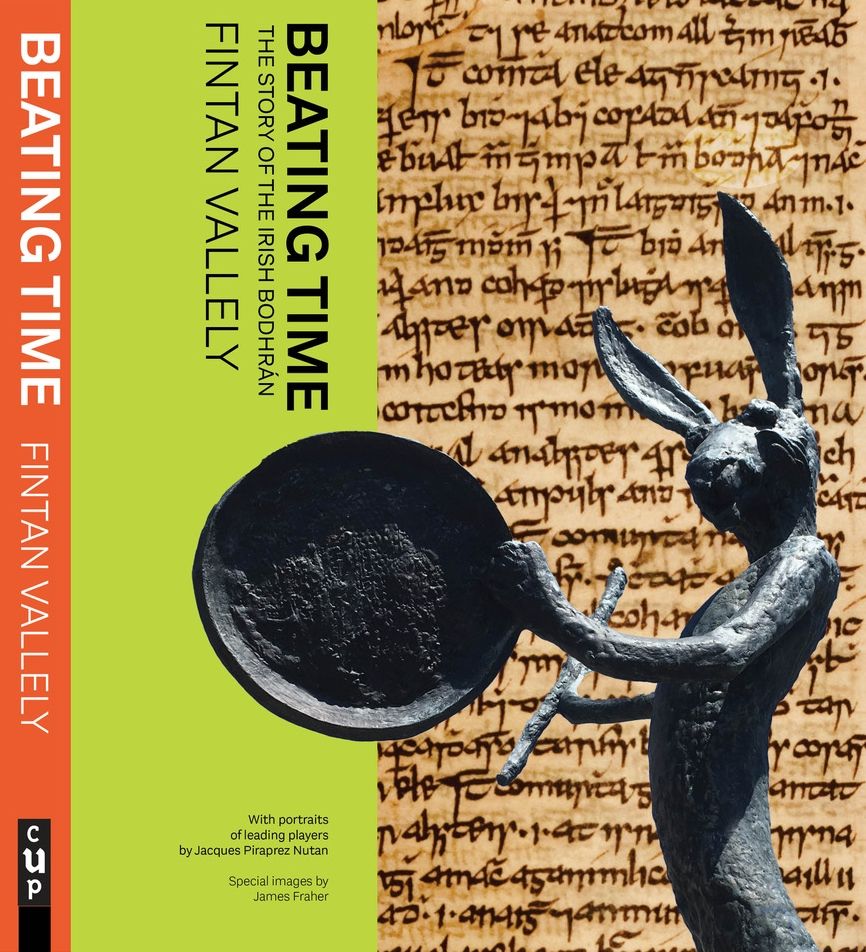

This week I’m off the sounds and into the pages! Coming off the book stack this installment is “Beating Time: The Story of the Irish Bodhrán” by Fintan Vallely. A lavishly illustrated tome that fits 17 chapters and 14 appendices into its 349 pages, it is a landmark study on one of the most maligned objects in Irish music. I feel confident in saying that you’ll not find a more comprehensive and persuasive examination of what began as, in essence, a utensil. It’s an excellent and important book about Irish music that trad fans will welcome.

The bodhrán has a complicated history. Although widely considered a musical instrument of antiquity and symbol of ancient Ireland, it really only traces its role in the Irish musical tradition back to middle of the 20th century. Before that, the story is more elusive and complex. Originally, the word “bodhrán” was used to describe a household container and winnowing tool – sometimes covered in skin, sometimes with a fiber weave – that had basic agricultural function. Eventually, the object found use as an improvised percussion instrument, in rituals like the Wren, but because of percussion’s near nonexistent role in Irish culture, its use was limited.

However, as Vallely argues, the instrument’s modern form has its roots in the tambourine, an instrument introduced to Ireland in a more refined form in the 18th century through minstrelsy and stage shows. This instrument that was copied and adopted as a percussive device for the Wren ritual, and if we flash forward to the 1950s, interest in the Wren led to the instrument’s use in traditional music. The eventual adoption of the word “bodhrán” was an intervention that didn’t occur until after 1960.

Vallely’s approach begins by looking at the object chronologically. He dips into a number of different subject areas, with early chapters providing important background that describes the lack of drumming traditions in Ireland as well as the associations drumming (particularly tambourines, which are crucial in the telling of this story) has had through history with religious cults, the military, and politics. In these chapters, Vallely works through misinformation associated with drumming traditions in Ireland, for example the claim that the “tiompan,” a first millennium string instrument, was actually a percussion device, attributing the misunderstanding to an early Anglo-Norman writer.

Valley’s examination of the etymology of the word “bodhrán” (and its variants) in chapter four is distinctly compelling and it feeds into chapter five’s exploration of how the word’s meaning has developed over time. Both are eye opening and provide really engaging analysis and as a side note, some will get a laugh out of “deaf person” as a once-accepted meaning for the word.

Another subject area Vallely looks at is the question of how Ireland came to have tambourines. He answers the question in detail, acknowledging the elements that suggest its early expression of the modern bodhrán, including its use in minstrelsy and stage shows. This leads to a larger analysis of local small-scale manufacture, the object’s role in the Wren tradition, and its ultimate resurgence in the 1950s and ‘60s through the efforts of John B. Keane, Bryan MacMahon and Seán Ó Riada’s group Ceoltóirí Chualann.

Chapter eight is particularly illuminating because it explores the representation of the object in art. The chapter includes many beautifully reproduced works that illustrate the presence of the instrument and in providing these, Vallely is really able to explore the interpretation of likely uses of the instrument.

Vallely looks at the representation of the bodhrán in literature in chapter ten, which provides the important context and the intellectual connective tissue to actually get readers to 1960s revivalists in chapter eleven. Later chapters, still, introduce us to renown bodhrán makers, players, regional traditions, and construction styles. The book ends with a look at a survey of the bodhrán in the 20th century and a comprehensive analysis of prior scholarship.

The amount of research that has gone into this work is breathtaking. As a musicologist, I recognize Vallely’s investigative methods and am thrilled by his no-nonsense approach. He’s done a very deep dive, taking a comprehensive and extremely rigorous look not only at how earlier scholarship has handled well known sources, but marries this analysis to novel sources. The methodological tools he’s brought to bear allow him to parse the peculiarities of early manuscripts (especially those in the Irish language) for non-initiates which brings better definition to a complex of materials that have sometimes been examined uncritically.

“Beating Time” will be considered the definitive statement on bodhráns. It contains valuable, voluminous and well-presented research that puts the bodhrán in fresh, compelling light. Beyond being an important contribution to traditional music in general, it’s an outstanding work of organology, the branch of musicology that concerns itself with the study of musical instruments. Will this book will make bodhráns more welcome at every session out there? Perhaps not. But will the history Vallely has written elevate the object’s status into a more respectable place? Most certainly. This book is an important study and comes with my highest recommendation. “Beating Time” is published by Cork University Press. See more here.