“Soldiers should not be ordered to carry out police duties. The military and police are

two separate animals."

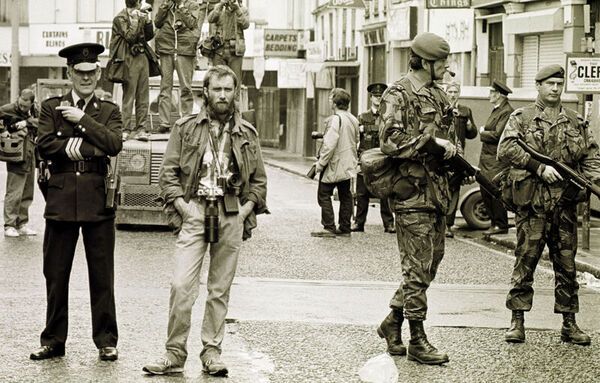

Those words were delivered to me in the summer of 1984 by a British soldier who had

just rescued me from police attack in West Belfast.

I was new to the territory, a veteran reporter for Newsday sent to Ireland on a year long fellowship from St. John’s University.

I had been stopped at a police checkpoint, fully compliant to orders barked in an Ulster brogue, a type of English in which I was not yet fully fluent. As ordered, I hit a button that popped open the trunk (“boot”) and exited the car.

Ordered to place my “filthy hands on the bonnet,” I paused for a confused couple of seconds before placing my palms on my head. A police officer - a member of the Royal Ulster Constabulary - lashed out with a baton collapsing my knees and toppling me onto the pavement. Next, a kick to the rib cage, the next landing an inch above my right ear, a third in the solar plexus.

The incident was spotted by a passing patrol of the Queen's Own, a British Army regiment. A soldier barked an order: Stand down. He picked me up and after a short conversation with the police ordered them “to be on their way.”

The sergeant asked about my health and patiently waited while I translated his accent, probably Yorkshire.

I replied, panting, a “Painful but not serious.”

I told him I was a reporter, leaving the scholar part out.

“I know exactly who you are,” the sergeant said. “We’ve already run the number plate on your car, learned everything I need to know. Another yank, dispatched to Belfast to cover the Troubles. I believe you live around the corner. This was your first dust up with the Peelers.”

It was true and, while not yet fluent I knew “peelers” was British slang for police.

“I believe this is your first lesson,” he said.

“The Peeler said you were taunting him, told you to put your hands on the bonnet and you put them on your head. He thought you were being cheeky. My guess is that you didn’t know the ‘bonnet’ is our term for the front of the car. I believe you call it ‘the hood.’”

Right again.

He was in a talkative mood, which in retrospect was probably cover for a bit of medical diagnosis to see if I had been more seriously hurt ty the peeler’s boots.

“This is the worst place to work I’ve every encountered,” he said.

“I’ve been a solider for more than a decade. This is the worst. Too many rules, too many consequences. When I was in the Falklands, if I discharged my weapon accidentally killing some Argie it was

no big deal, I’d get some stick from an officer about wasting valuable ammunition.

"I do the same thing here, chances are the victim would turn out to have a cousin who is a policeman in Chicago and I’m the cause of an international incident. Here in Belfast I’m not allowed a mistake.”

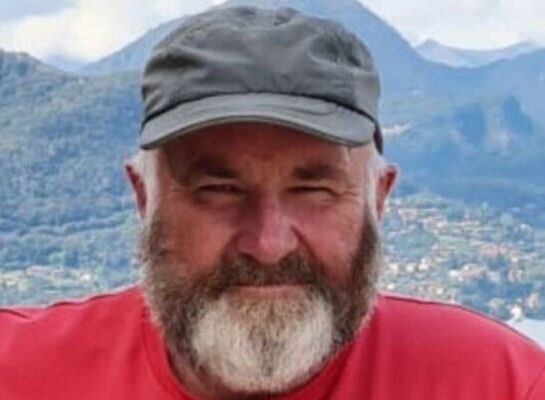

Against the backdrop of the deployment of the National Guard and U.S. Marines in Los Angeles, veteran journalist Jim Mulvaney reflects in the above article on a time when British soldiers were all too often deployed in Northern Ireland in situations that they were not specifically trained or suited for. Mulvaney was one of the first, and ultimately one of the few, American reporters to be based in Belfast during the height of the Troubles. Today he lectures at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan.