Don’t call it a retrospective.

Yes, the title of the exhibition that will run at the Noble Maritime Collection through Jan. 18 is “Bill Murphy: Waterfront Tales, 1975-2025.”

But the artist who grew up the son of an NYPD officer on Staten Island’s South Shore, has done lots of other types of work.

The water lends itself to all sorts of possibilities, Bill Murphy believes, but the waterfront is only about 20 percent of what he does.

“I could have a show of portraits, landscapes that aren’t waterfront-related, figure studies, things that can’t be labeled,” the artist said. “I’ve been free to move around, different mediums, all kinds of drawing mediums, prints, etchings, lithography, painting, different subjects. Maybe I’ve a restless attention span, and I need to shake it up from time to time.” (See his website here.)

And don’t call Murphy a preservationist or a documentarian. It’s true that some of the exhibition’s 45 waterfront images are of places that have radically changed or of views that have disappeared. Over the years, too, he drew or painted exotic scenes that were holdovers from another time and now are no more.

It’s mostly accidental, though, in contrast to his early mentor, an artist who ran off to sea as a 15-year-old, and for whom the museum is named, John A. Noble.

Said the outgoing Executive Director Ciro Galeno Jr. (and the exhibition’s co-curator with Megan Beck. his successor), “Noble was using his art intentionally as a form of historic preservation.

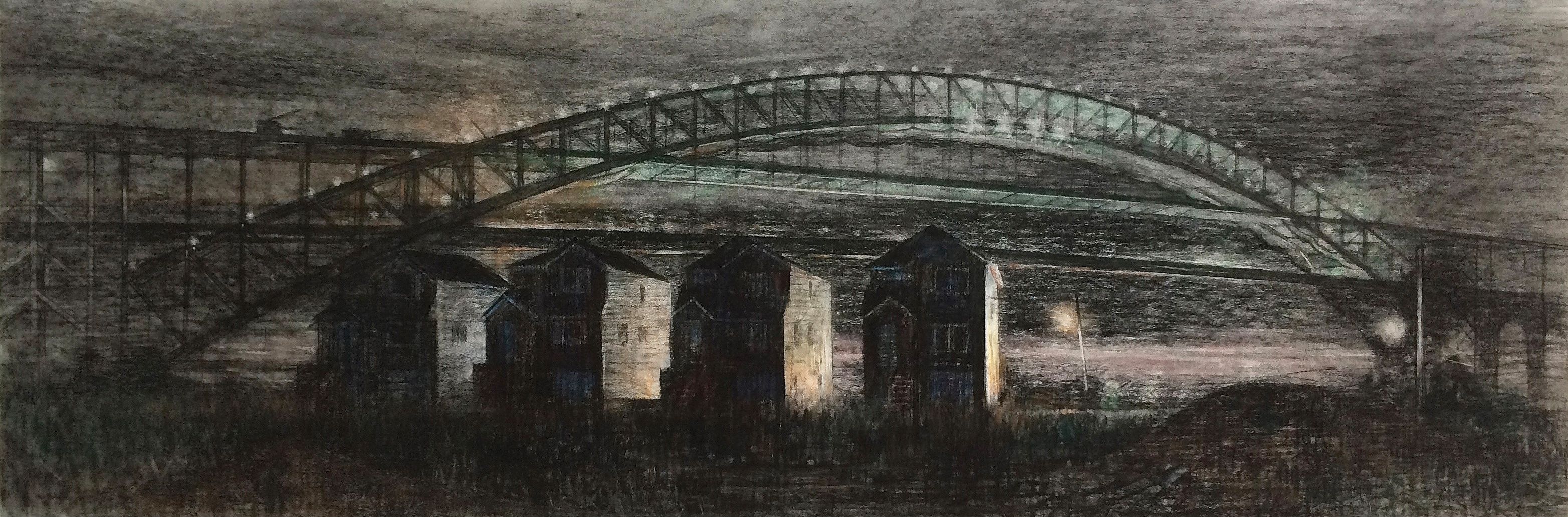

“New Construction,” by Bill Murphy. Charcoal and pastel, 2017.

“He wanted us to recognize we’re a maritime city,” Galeno said.

“John did very few pictures that were not maritime-themed,” Murphy said during a recent conversation at the museum.

The Noble Maritime Collection’s most ambitious project arguably was the restoration of its spacious building, which was derelict when it took it over in 1992. The Sailors’ Snug Harbor was one of the first retirement homes in the nation and from the 1830s onwards provided for those who’d left for sea as boys and were “aged, decrepit, and worn out seamen” at the end of their working lives. In a posthumous tribute, volunteers called the “Noble Crew” donated $1 million in labor and materials.

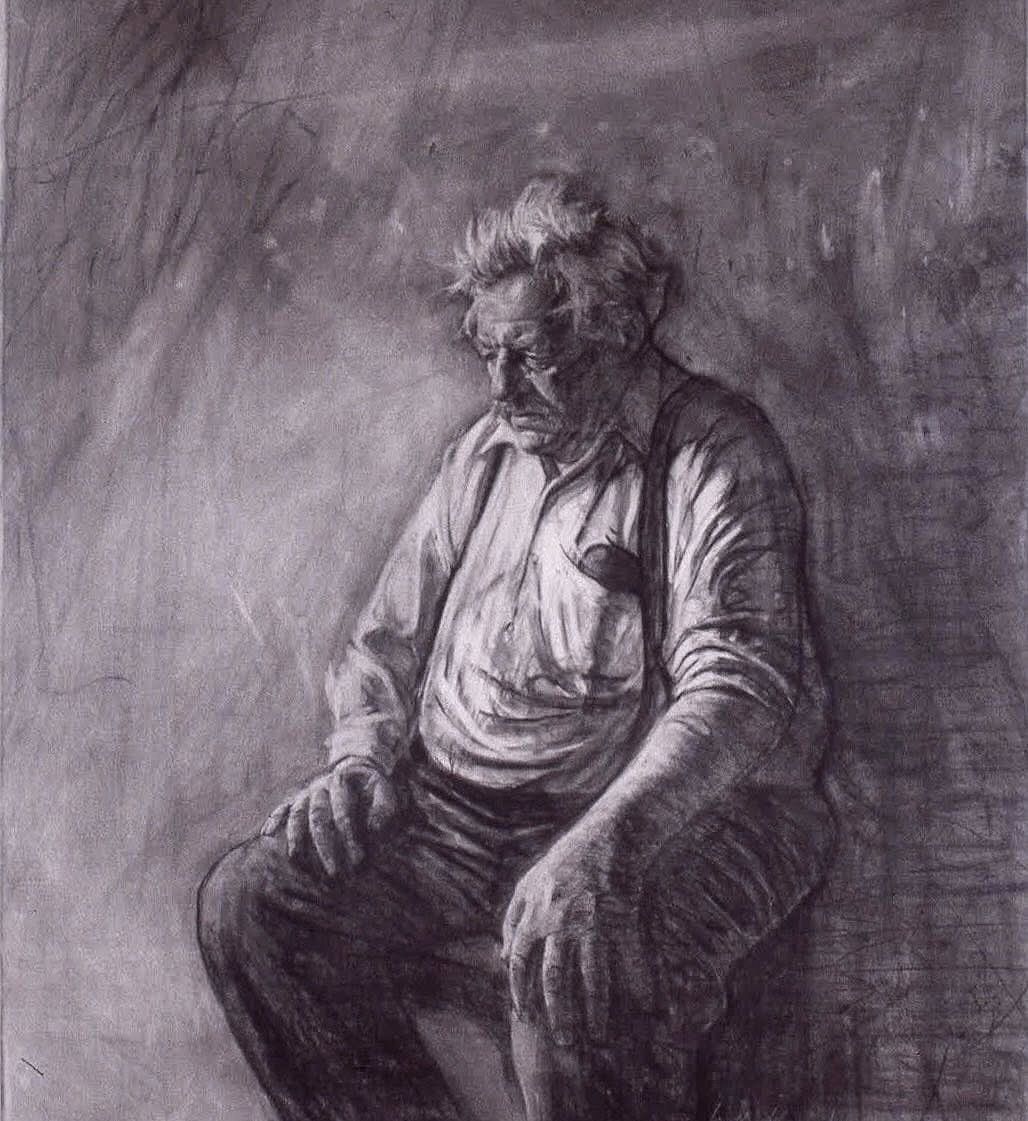

The Noble Maritime Collection displays the artist’s floating studio, and, as part of the current exhibition, on loan from the Collection of the Staten Island Museum, Murphy’s portrait of him done in 1982, the year before his death at age 70.

One departure from Murphy’s generally accidental role in documenting and preserving the past is what he has named the “Kreischerville Experience.” He recalls in one of the essays that accompany individual pieces in the show, “I worked with a real frenzy, believing that at any moment the wrecker’s ball might come down and wipe my subjects from the face of the earth.

“The pressure of knowing no one else would do that particular work made me impassioned in a way I never knew, before or since.”It began with a question in the middle of the first decade of the 21st century: “Have you ever drawn those old barges over by the Outerbridge?” When Murphy looked, he couldn’t find them. Then a student of his at Wagner College told him there was something out on Arthur Kill Road he might like to draw.

Murphy remembers, “He explained that in place of the old Kreischer Brick Factory a multi-acre housing development was in the process of going up, revealing, for the first time in years, a long row of decaying barges, ferries, schooners and other wooden sailing vessels.”

The artist reverted to the area’s old name for his two-year project, Kreischerville, which had been changed to Charleston due to the anti-German sentiment sparked by America’s participation in World War I.

From the late-19th century to the middle of the 20th, it was a hub of commercial shipping as well as the home of the Kreischer Brick Factory.

“To me ‘The End Days’ is an elegiac picture which attempts to sum up my experience recording the Kreischerville area,” he writes of one work. “Although I never officially inquired about it, it did seem that the wall in the center is the last remaining part of the brick factory. It still stands still, to this day.”

Murphy had made it his task to record the wrecks before they disappeared, but in fact they’d become the water line, and “to remove them would severely alter the tide pattern as well as native species such as Canadian geese, muskrats, deer etc.”

Nonetheless, some of the wrecks Murphy painted during the Kreischerville Experience were blown away by Irene in 2011 and Sandy in 2012.

Bill Murphy was born in 1952 and came of age when the art world was expanding rapidly in New York and beyond. Neither of his parents was enthusiastic about his desire to be an artist. “They came out of the Depression. They were middle class,” he said. “My father didn’t know what to make of it. That’s not the world he came from, Brooklyn.

“My mother was a little more supportive in that she herself wanted to go to art school, but her parents were, ‘You’re not going to study art.’

“She got a job, [later] became a homemaker. That’s how it was then,” he said.

“My father was from the generation that fought in the Second World War, and never really talked about that huge aspect of life.

“They didn’t try to stop me,” he said, “They didn’t know how an artist would survive.”

His parents wanted him to be a teacher. “Which I ended up doing,” he said, with a laugh, “though I didn’t plan to.”

Murphy had a part-time teaching job at Wagner College that became a full-time one, professor of visual arts, after he got an MFA from Vermont College in 1984. He retired in 2019 and teaches now at the Art Students League in Manhattan.

Already at age 16, thanks to a courier job on Wall Street, Murphy learned that the regular 9-5 wouldn’t be for him. After his graduation from the School of Visual Arts he did illustration work for the rock magazine Crawdaddy, as well as other publications. He also got part-time work as a delivery man for a friend’s family seafood store. It allowed him to be out in the open and to get to know the North Shore.

Murphy remembers in one essay for the exhibition, “What would become one of my main delivery routes, Richmond Terrace, absolutely knocked me out; a street I would begin a lifelong love affair with. An avenue of abandoned vessels and rusted beams, deserted warehouses and cast-iron dreams.”

He recalls, “It took a few decades for the sense of exploring to become exhausted, and it eventually did. But in those days it was a great feeling to launch out for a day of looking and maybe drawing/painting.”

Freedom could have its less than romantic aspects, however. For example the plein air painting beloved by the Impressionists tended to attract in the 20th century, “pedestrian traffic with the unpredictable onlookers wanting to engage me in a conversation about how they have an uncle who paints or, by chance, would I be able to do a drawing of their dog, and they will even pay me.”

He moved to the North Shore in early adulthood, and while it was more liberal and more diverse, as well arts- and artist-friendly, it was still very much Staten Island.

“I was well into my 40s when the concept finally hit me that I was an island dweller,” Murphy writes, “and being such, I am inherently different than probably 99% of the rest of the world.”

Galeno, who is of three-quarters Italian heritage and one-quarter Irish, said, “As Staten Islanders we have a special relationship with the water.”

Murphy is almost second generation in that his mother arrived in the borough with her Italian-American family in the late 1920s at age 3. Even his father, who grew up in a Brooklyn Irish family, became a relative pioneer in Staten Island terms when he settled down upon his marriage in 1947. (Murphy said a DNA genealogy test showed his family to be 50 percent Irish, but the “mostly Italian” assumption on his mother’s side was undermined by the revelation of apparently French and Swedish roots.)

The elder Murphy didn’t get to see much of his son’s career. He had a serious heart attack at age 41 in 1960, which stalled his ascent in the police department. He retired at 50 and died at age 60 in 1979, when the artist was 27.

His mother kept newspaper and magazine articles and when she moved to Florida, he sent her on any new pieces in which he was featured or mentioned. “She had quite a scrapbook,” Murphy said of the would-be art student, who died seven years ago at the age of 92.

There was another important elder in the life of the artist during his younger adult years. Murphy suggested to his girlfriend, who worked for the newspaper at Wagner College, that she interview John Noble; his assistant was a friend and she would arrange it. Erin Urban did interview him during what was their only meeting. After his death she worked for his family and she is the founder of the Noble Maritime Collection. (Murphy and Urban later married and are now divorced; they have a son, Sam Murphy.)

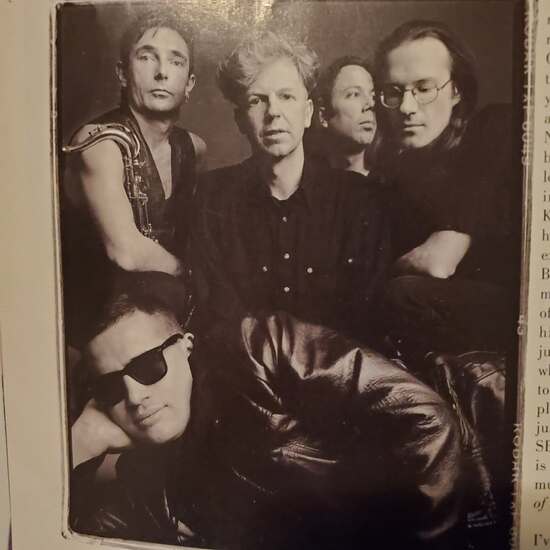

Artist Bill Murphy s showing at Staten Island’s Noble Maritime Collection through Jan. 18. [Photo by Peter McDermott]

John A. Noble was born in Paris in 1913, the son of the American painter John "Wichita Bill" Noble. His family came to America when he was 6, and on a return trip to the land of his birth he studied for a year at the University of Grenoble, where he met his wife and lifetime companion, Susan Ames. Back in New York, he resumed working as a seaman on schooners and in marine salvage, which he’d begun doing in 1928. In that year, the Noble Maritime Collection’s website says, “while on a schooner that was towing out down the Kill van Kull, the waterway that separates Staten Island from New Jersey, he saw the old Port Johnston coal docks for the first time. It was a sight, he later asserted, which affected him for life. Port Johnston was ‘the largest graveyard of wooden sailing vessels in the world.’”

Noble started his full-time career as an artist in his floating studio in 1946, but continued to feel connected to those he’d worked with. "I'm with factory people,” he said, “industrial people, the immigrants, the sons of immigrants.”

He once took Murphy to task for his work “Three Bridges,” remarking “You can’t tell Brooklyn from Manhattan!” (The latter had failed to reverse the original drawing, creating a print showing a mirror image). “It doesn’t matter, John, it’s just a lithograph,” Murphy said. That enraged Noble, who replied, “The hell it doesn’t matter! Men died to build that bridge!”

It was to a more upbeat Noble he confessed his desire to go on a drawing tour of France and England. “Don’t go to Europe, Murphy,” the older artist responded. “Go to the Gowanus Canal [in Brooklyn].”

“And he was right,” comments Murphy, who has been collected in the British Museum and published in Paris. “It was and still is a visual treat for an artist who likes the old, industrial world.”

In his reflections on his Kreischerville Experience of two decades ago, Murphy writes, “To me it was a secret place, a museum in the wild, and it was my job to somehow get it under glass – and keep doing so until the developers turned it into ash.

“I think this interest is aligned with my interest in eastern philosophies. One of the core beliefs of Buddhism is the impermanence of everything in our world. Our suffering comes from trying to grasp, to hold, and slow down the natural movement of transformation which unceasingly animates all objects and beings.”

“John A. Noble,” By Bill Murphy. Charcoal on grey toned paper, 1982, Collection of Staten Island Museum.

“It’s been pointed out to me that my fascination with these decaying forms is really a statement about the passing of time, my time, my life. I can’t deny that in middle age one becomes well aware of what in eastern religions is known so well - the transient nature of life.”

Murphy continues, “In 2007 I had an exhibit of these works, and I called it ‘Undead.’

“The dictionary defines dead as ‘showing little indication of feeling or vitality.’ With this title, I tried to sum up my feelings about the abandoned and forsaken things I had seen and drawn; nothing could be truer than to say they are as alive today – and as full of feeling - as when men worked on them; when they carried or received sailors; when they were full of ‘life’ in the obvious sense.”

Murphy writes, “The inner soul of the thing grows proportionately as the outer shell decays.”

“Bill Murphy: Waterfront Tales, 1975-2025” is showing through Jan. 18, 2026, at the Noble Maritime Collection, on the grounds of Snug Harbor Cultural Center, 1000 Richmond Terrace, Staten Island, N.Y. 10301.

It’s open Wednesday-Sunday, 12 to 5 p.m. It has a pay-what-you-wish admission policy. Members, children under 10 and care partners are free. The museum participates in Museums for All, a program of the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Through Museums for All, those receiving food assistance (SNAP benefits) will not be asked to make a donation for admission to the museum.

Sailors’ Snug Harbor, a 28,500-sq.-ft. building, is accessible by all throughout.

The museum will be closed on Christmas Day and New Year's Day.