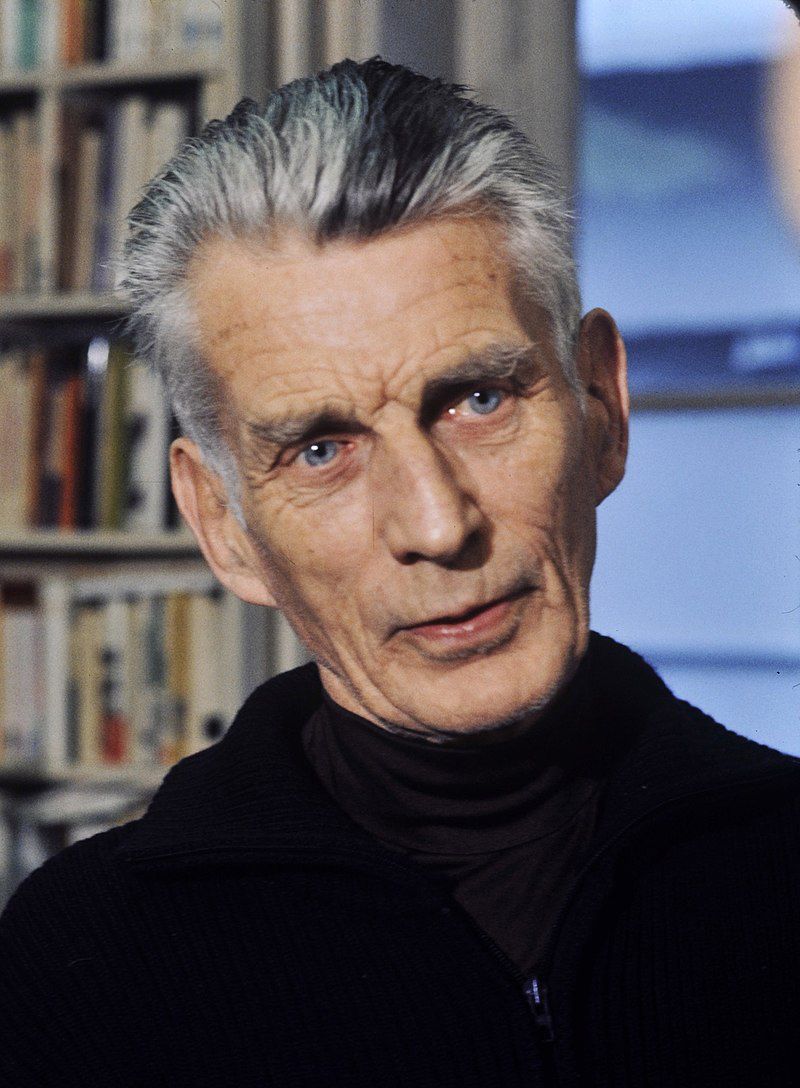

For Samuel Beckett, death is far from the end.

In the final months of 2025, Beckett has burst onto the New York stage and has had a higher profile than nearly any playwright active since the postmodernist’s death in 1989.

With productions of Waiting for Godot at the Hudson Theatre, Krapp’s Last Tape at NYU Skirball Center, and Endgame at the Irish Arts Center, audiences have come to appreciate the longevity of his idiosyncratic genius, though the playwright revels in posing questions that will not help anyone sleep soundly and certain of his characters dismiss the universe and everything in it the way one might toss out a moth-eaten hat.

There are many reasons to go see Beckett productions, and ideally the ideas and writing would be paramount in people’s minds.

But the world is what it is, and the luring of A-list talent to take on leads in two of the plays has not hurt. Keanu Reeves appears as Estragon in Waiting for Godot. Legendary Irish actor Stephen Rea takes center stage as the solo in Krapp’s Last Tape.

The Irish Arts Center production of Endgame brings fresh talent to a play that has intrigued and baffled audiences since its first run at London’s Royal Court Theatre on April 3, 1957.

That initial production was in French and featured Roger Blin as Hamm, Jean Martin as Clov, Georges Adet as Nagg, and Christine Tsingos as Nell.

In the new version, the actors in those four roles are Rory Nolan, Aaron Monaghan, Bosco Hogan, and Marie Mullen, respectively. Running from October 22 to November 23, the production provides a coda to this latest Beckett season and, for the curious, a portal to the heart of his oeuvre.

If death is not the end of a creative mind’s presence in our culture, the imminence of our physical demise does bring ruminations and reflections. Endgame is a series of conversations, some playful and some heated, among the four leads, who are pitiable in their dependance yet, in the midst of their flailings, rise to comic eloquence.

At least their hearts are in the right place.

Clov keeps offering to attend to Hamm’s needs for pills, medicine, or food, yet Hamm’s aggressive lines of questioning late in the play suggest Clov may be the needy one. Nagg asks Nell for a scratch, then offers to give her the same. Nell tells Nagg that she has been crying or at least trying to do so, then they banter about where a scratch would help most, leading to a riff on “vein” and “vain.”

The random gab segues into metaphysical irony as Nagg tries to cheer up Nell with the story of a tailor who takes heat from a customer for taking three months to get a pair of trousers ready for use, when God made the world in just seven days.

The tailor asks the customer to compare the state of the world and the state of the trousers and to draw a conclusion.

The playful dalliance with philosophical and metaphysical questions draws on as Hamm and Clov have an exchange about the meaning of their lives or the lack thereof.

Clov has a laugh at Hamm’s expense after the latter dares to entertain the possibility that they have not wasted their time on earth in the pursuit of illusions.

That reaction prompts Hamm to ask what might happen if a “rational being” came back to the world and tried to make sense out of their doings.

The discussion shifts back to the mundane as Clov cries aloud that he has a flea on his body, but it might not be such a petty matter after all.

Hamm interjects: “But humanity might start from there all over again! Catch him!”

Viewers who take in Endgame, with its mélange of humor and despair, may come to take an interest in the explorations in other Beckett works of how men and women should fill their finite number of days on this mortal coil.

Besides advancing Beckett’s reputation as a playwright, one hopes that the new productions will drive more people to seek out his fictions, many of which languish in obscurity.

As the author’s experiences in the early years of the last century impressed on him, it is far easier to set off on the paths of oppression, dogma, violence, and retribution, and to become locked into vicious cycles, than to find answers that will lead to some form of satisfaction when people end up at that stage of life depicted in Endgame.

In stories such as “Fingal,” one of the pieces published in 1934 as the collection More Pricks Than Kicks, Beckett presents a vision of Ireland as a place whose natural beauty contrasts with a spiritual void that generations have tried and failed to fill.

Belacqua, the protagonist of “Fingal” and the other tales, goes with his girlfriend Winnie on an outing in the titular county, where they admire the coast, estuaries, dunes, hills, mountains, and woods. But what they really find to be of interest is the Portrane Lunatic Asylum, whose bounds are a little hard to determine for travelers on the outside.

The inclusion of that detail does not seem random at all. Beckett lures the reader into his vision of a society where judgments as to who belongs where, who is sane and who will be subject to the whims of those who claim to have the only legitimate viewpoint, are subjective, arbitrary, yet binding.

“Now the loonies poured out into the sun, the better behaved left to their own devices, the others in herds in charge of warders,” he writes.

Beckett goes on to give an account of a playground where the “milder patients” while others bask in the sun and still others form marauding gangs.

Anyone who, like the McCourt brothers, has survived the rigors of a sectarian education, or who has weathered the trauma of the Troubles and the brutality of a prison like Long Kesh, will find in “Fingal” a mosaic of unappealing choices.

It evokes a society where the pliant live in humble subjection, watching football games and getting drunk under the threat of coercive and punitive measures from the self-appointed enforcers of one or another order.

Late in the story, Belacqua renounces the charms of the countryside and backs out of his promise to meet up with Winnie and a director of the prison.

They ask others to try to help track him down but, we learn, their efforts are in vain because Belacqua has installed himself in a pub and taken to drinking in a manner that puts off the establishment’s owner, who has no doubt seen more than his share of binge drinkers.

In the vision Beckett presents in “Fingal,” there are no pat answers to the metaphysical questions that come across with even greater power and urgency in his plays.

As audiences watch his characters strut and fret on the New York stage, we should hope that they will enjoy the experience enough to turn to a more holistic engagement with Beckett’s vision of Ireland and the universe.