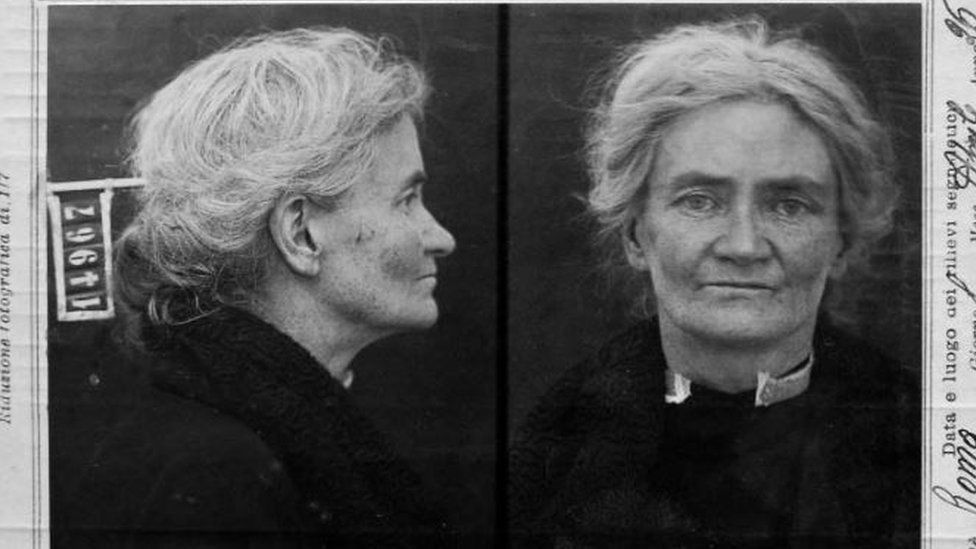

It seems like the entire American nation is focused on the tragic assassination of Charlie Kirk and whether it signals a return to the political violence of the 1960s and ‘70s. People fear that in today’s overheated political climate fanatics are ready to murder those whose politics threaten them. The Kirk saga reminds me of an assassination attempt that might have changed the world, and which today is being re-evaluated. The target of the assassination attempt was Benito Mussolini, the founder of fascism and leader of Italy from 1922 to 1943. Amazingly, the assassin was not an Italian; she was an Anglo-Irish woman from Dublin, Violeta Gibson. Her story and the controversy surrounding its interpretation today are worth reflecting on.

Nothing in Gibson’s background would ever suggest that she would become an assassin. Born in posh Dalkey and raised in aristocratic splendor on Merrion Square, Gibson’s upbringing was one of great privilege. Her father, a lawyer and ally of Edward Carson, became Baron Ashbourne and went on to serve as Lord High Chancellor of Ireland from 1885 to 1905. She grew up dividing her time between Dublin and London, and at the age of 18 became a debutante in the court of Queen Victoria.

Though she was born and raised as part of the elite, she was not immune to suffering. She was a sickly child who suffered with scarlet fever and pleurisy. She also suffered from anxiety and was prone to fits of rage. She grew into a "tiny" woman, one who was mentally and physically frail. A few years later, she contracted Paget's disease (an abnormal breakdown of bone tissue) and had a mastectomy that left her with a nine-inch scar. She then returned to England where surgery for appendicitis left her with chronic abdominal pain.

Perhaps because of her physical suffering, Gibson grew interested in religion and at the age of 26 in 1902, she took the unusual step for someone in her social class by converting to Catholicism. Over the next few years, her interest in religion bordered on fanaticism. She went on retreats, followed the Jesuit scholar John O'Fallon Pope and became obsessed with the ideas of martyrdom and "mortification. “

Benito Mussolini during the early years of his dictatorship.

She suffered emotional trauma in addition to the physical pain she dealt with. She married an artist, but soon after her marriage she was widowed. By 1922, she had suffered a nervous breakdown after the death of her brother and was committed to a mental asylum, having been declared insane. Two years later, along with a nurse named Mary McGrath, she traveled to Rome where she lived in a convent. A pacifist, Gibson also followed current events closely and grew appalled by Mussolini’s violent rhetoric. In February 1925, she somehow managed to get a pistol and shoot herself in the chest but miraculously survived.

By this point, she was convinced that God wanted her to kill someone as a sacrifice. In March 1926, Gibson’s mother passed away traumatizing her even more and pushing her to extreme action. The following month she had decided to kill Mussolini. On April 7, 1926, Gibson went to Palazzo del Littorio with a pistol wrapped in a black veil, and a rock she planned to use to break Il Duce’s car windshield as Mussolini was driven through Rome's Piazza del Campidoglio, where he was supposed to make a speech.

Mussolini instead emerged on foot just a few feet from Gibson. She stepped out from the crowd and fired a shot at point blank range that grazed his nose. Gibson tried to fire another bullet, but her pistol jammed and did not fire. Mussolini had been very lucky. He had just turned his head to look at a group of nearby students who were singing a song in his honor, which caused the bullet to graze his nose rather than hit him square in the face. A mob grabbed Gibson and threw her to the ground, ready to lynch her on the spot. Police escorted her away before the furious crowd could exact their revenge. Hours after the attempt on his life, Mussolini reemerged in public, with only a bandage on his nose, but no other wounds. Later he said that while he was ready for “a beautiful death” he did not want to die at the hands of an “old, ugly, repulsive" woman. The assassination attempt triggered a wave of popular support for Mussolini, leading to the passage of pro-Fascist legislation which helped Mussolini consolidate his dictatorship.

Gibson told police detectives she had shot the Italian leader “to glorify God,” who had sent an angel to keep her steady. The Gibson family wrote to the Italian government to apologize for her actions.

She suffered various cruelties and indignities within the fascist prison system. Because she was a unionist who refused Irish citizenship, she was then deported to England, sparing Mussolini the embarrassment of a public trial. Her family had secretly arranged to have her committed to an asylum - St. Andrews Hospital in Northampton, where Lucia Joyce, James Joyce's daughter, would later be committed.

When Gibson passed away in 1956 there were no mourners at her funeral. For years, no one showed any interest in the Gibson saga, but that is now changing. In 2010, British historian Frances Stonor Saunders published “The Woman Who Shot Mussolini,” a biography of Gibson. In 2014, Siobhán Lynam produced a radio documentary for RTE about Gibson based on Stonor Saunders book. Barrie Dowdall and Siobhán Lynam also produced a film drama-documentary based on the radio documentary, “Violet Gibson, The Irish Woman Who Shot Mussolini. “

Cavan singer Lisa O’Neil wrote a 2018 song recounting the assassination attempt from Gibson’s point of view. Her story is also the subject of Noggin Theatre Company's play “Violet Gibson: The Woman Who Shot Mussolini,” written and performed by Irish playwright and actor Alice Barry. Gibson is also the subject of Shane Tivenan's short story, “Flower Wild,” which won the RTÉ Short Story Competition. In March 2021, Dublin City Council approved the placement of a plaque on her childhood home at 12 Merrion Square. to commemorate Gibson as "a committed anti-fascist.” Dublin councilor Mannix Flynn who made the motion for the Merrion Square plaque said at its unveiling, “It is now time to bring Violet Gibson into the public’s eye and give her a rightful place in the history of Irish women and in the history of the Irish nation and its people.”

Anti-fascist or mad woman? Obviously, a debate about how to interpret Gibson has ensued. Director Barrie Dowdall remarked, “It suited both the British authorities and her family to have her seen as ‘insane’ rather than as political. "Establishment outrage was all the greater because she was seen as not only betraying her class, but also her gender," said Dowdall. "If a man had done this, there'd probably be a statue of him."

In a country like the United States where procuring a firearm is so easy Gibson’s actions are easy to repeat. Let’s pray that cooler heads prevail.