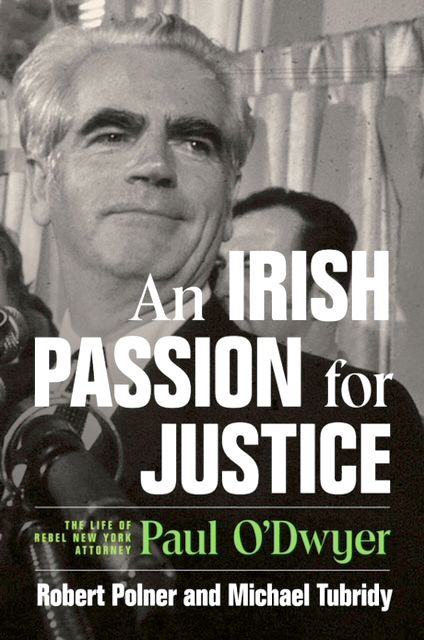

Fifty years ago this week, Paul O’Dwyer led New York’s St. Patrick’s Day parade as Grand Marshal. By this time, O'Dwyer had long been a presence in the news: a forceful progressive with a white pompadour, bushy eyebrows, and County Mayo cadences. Families throughout New York and well beyond recognized him as a politician, a lawyer, and an activist who stood up for outcasts and underdogs, defended the targets of federal and state prosecutors, and espoused freedom from British rule in Northern Ireland.

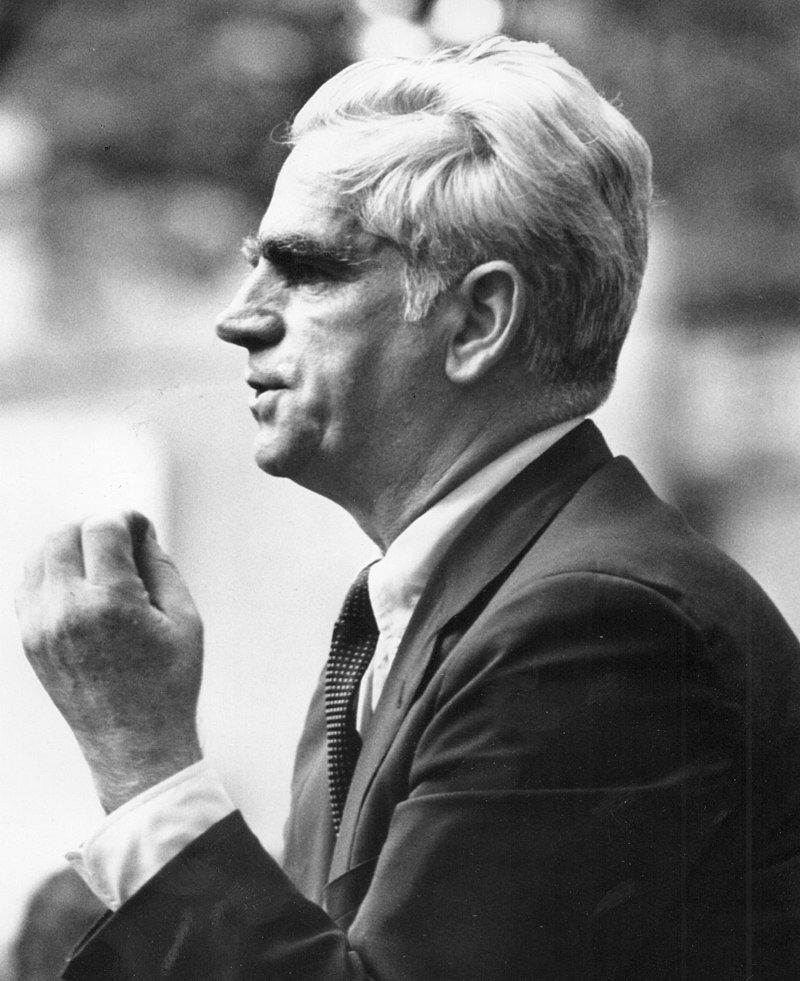

Paul O'Dwyer in 1968.

The youngest brother of the last Irish-born New York mayor (Bill O’Dwyer won two terms following WWII), he lost more races for public office than he won, starting with a close contest for Congress against Jacob Javits in 1948. The most-remembered of his Democratic campaigns was a maverick 1968 bid for the U.S. Senate in opposition to an “immoral war” in Southeast Asia advanced by the leader of his party, Lyndon Johnson.

Michael Tubridy. Photo by Shihan Zheng.

But when he wore the top hat in the 1974 celebration on Fifth Avenue (an honor earned by his brother, Bill, and later by his youngest son, Brian), O’Dwyer was also regarded as something of an anachronism. His battles in New York courthouses and on the campaign trail dated to the Great Depression and the era of rock-solid Irish-American membership in Tammany Hall and the New Deal coalition.

Born in the Irish hamlet of Bohola in 1907, buoying up in the big city in 1925, he was three decades older than the new crop of Democrats who in the 1960s challenged, with his support, the influence of “boss rule” over city government and helped seed opposition within the party to the Vietnam War.

Robert Polner. Photo by Molly McIntyre-Polner.

O’Dwyer endured both the doubts of the Young Turks that an Irishman could be liberal, and more broadly the slings of some members of his ethnic group who mistook him for a Communist (“Pink Paul”). But his participation in New York’s trade union movement and liberalism resonated with others.

And today, more than a quarter-century since he died in 1998, O'Dwyer's journey reflects how an individual, even an immigrant who entered America’s “golden door” with $25 to his name, can create effective coalitions, stand up to the American far right, and compel a nation born of a revolution against the British Crown to remember its founding democratic ideals.

Peter Quinn told us that one of Paul O’Dwyer’s most striking traits was his remarkable consistency as an advocate for scapegoats and the oppressed. It stemmed, the historical novelist said, from a “refusal to stray from ideals acquired in the revolutionary Ireland of his youth.”

We would add that it also arose from his attraction to what was then and still is, apparently, a radical idea: that all people should have a say in their government and enjoy equal rights under the law. It was from his father, an organizer of the Irish National Teachers’ Organization, that O’Dwyer inherited the view that unions are essential for curbing perilous working conditions, exploitation, and economic inequality. He remained faithful to the labor movement, along with his union card stemming from his stint as a Brooklyn longshoreman in the 1920s and later representation of the fiery Irish-born Transport Workers Union leader, Michael Quill.

As president of the New York chapter of the National Lawyers Guild, an important left-wing alternative to the American Bar Association, O’Dwyer, in the wake of WWII, submitted briefs opposing prosecutions under the Alien Registration Act (or Smith Act). He defended labor leaders and fellow attorneys facing congressional interrogation and deportation during the “Red Scare” of the 1950s, supported challenges to anti-union laws in Florida and Alabama, and won redress for New York City teachers dismissed for supposedly treasonous leanings.

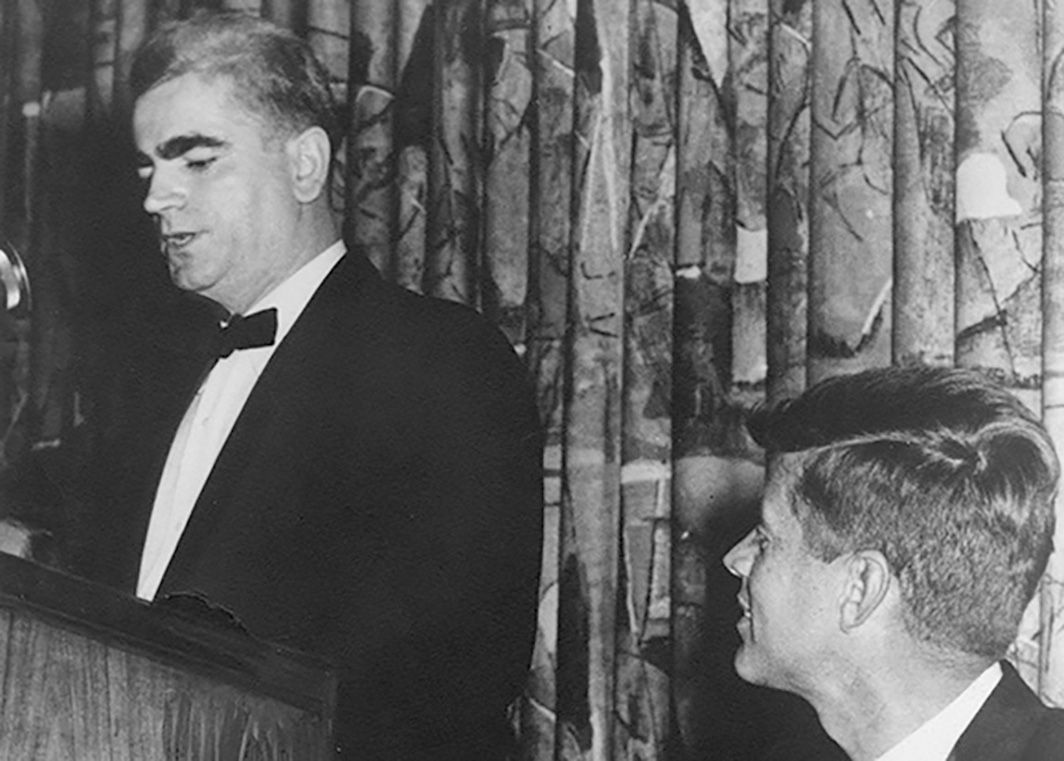

Paul O'Dwyer speaks, President Kennedy listens.

O’Dwyer took risks in reactionary periods. Whether challenging rampant housing and job discrimination in New York, working with Black political activists contesting Mississippi’s white-supremacist slate of delegates to the 1964 Democratic Convention, or volunteering as an attorney and a poll watcher in the Deep South, his commitments rested on principles of fairness.

He viewed interracial protests against segregation, voter suppression, and inequality as the primary catalysts for a more democratic and fair society.

“The ideals should always come first” and the compromises later, he advised younger activists. He approached civil rights and the antiwar movement that way. When his friends in the Irish American community asked why he cared so much about mistreatment of Blacks in the Jim Crow South, his answer characteristically traced back to his upbringing amid the Irish War of Independence and the British military recruits known for their improvised uniforms and violent impunity.

“Peter Quinn told us that one of Paul O’Dwyer’s most striking traits was his remarkable consistency as an advocate for scapegoats and the oppressed. It stemmed, the historical novelist said, from a “refusal to stray from ideals acquired in the revolutionary Ireland of his youth.” “The ‘Black and Tans,’” O’Dwyer explained, “used to drive through the town, shooting it up. It was not too different from Mississippi.”

The issue closest to his heart, Irish unification, also stemmed from his Mayo upbringing, specifically his family’s opposition to the 1921 Anglo-Irish Peace Treaty establishing the semi-independent Irish Free State and leading to the partition of Ireland.

Epithets and brickbats flew from the sidewalk when then-Mayor David Dinkins, a longtime O’Dwyer ally, joined up with the small contingent. Though physically vulnerable, Paul was still a politician beyond his years. Within two decades, the U.S. Supreme Court would legalize same-sex marriage, as would the Republic of Ireland.

Decades later, O’Dwyer sparked varying degrees of consternation and complaint for refusing to denounce IRA violence in The Troubles in Northern Ireland, and - as we learned researching our soon-to-be-published biography of O’Dwyer, 'An Irish Passion for Justice' - after circulating the diplomatic proposal of a Protestant paramilitary leader in Belfast.

He was never written off by fellow Irish Catholics, however, because he depicted violence in the North as causative, the result not only of the British government’s “legalized lawlessness” (in the recent description of historian Caroline Elkins), but of the economic and political imbalances pitting Irishman against Irishman. In the end his efforts helped persuade Bill Clinton to grant Gerry Adams a visa to travel to the U.S. and name an envoy to mediate The Troubles.

The actions blazed a path toward the Good Friday Agreement. On St. Patrick’s Day fifty years ago, O’Dwyer had just been elected City Council president and championed the Fort Worth Five, a quintet of middle-class Irish New Yorkers jailed after refusing to answer a Texas judge’s questions about alleged IRA gun-running.

When coupled with his small law firm’s frequent defense of locally intercepted IRA volunteers facing extradition to British justice, he probably was never more popular. But his press for justice in America and the United Kingdom took an even more dramatic turn in 1991 when he marched in the St. Patrick’ Day procession with the aid of a cane and his spouse Patricia Hanrahan alongside members of the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization, or ILGO.

Epithets and brickbats flew from the sidewalk when then-Mayor David Dinkins, a longtime O’Dwyer ally, joined up with the small contingent. Though physically vulnerable, Paul was still a politician beyond his years. Within two decades, the U.S. Supreme Court would legalize same-sex marriage, as would the Republic of Ireland.

American politics today is conducted as if under a curse, with deep polarization, election denialism and insurrection, attraction to authoritarians, and opportunistic exploitation of fear and prejudice.

But the late Paul O’Dwyer would not likely have been deterred by the current climate. He arose, according to Quinn, from “a tradition of democratic resistance that went back to the United Irishmen of the 1790s. At a time when many Irish Americans moved right, he was - and remains - an embodiment of the Irish traditions of anti-imperialism and social reform. He never gave up, never despaired, never abandoned his commitments or surrendered his ideals.”

As former Long Island congressman Peter King, a conservative Republican, said: “Paul was Paul. He really had his moral compass, and whether you agreed or not, you knew where he was coming from.” It was a quintessentially Irish place, where defiance of - and negotiation with - the status quo went hand in hand with seeking greater dignity for oneself, for one’s people, and for all. Robert Polner and Michael Tubridy are the authors of "An Irish Passion for Justice" (Cornell University Press, May 15, 2024), a biography of the rebel New York attorney Paul O'Dwyer, who fought for civil rights and justice throughout the 20th century.

Polner reported extensively for Newsday, the New York Daily News, and other newspapers. Now a public affairs officer with NYU, he has co-written or edited four other books, including "The Man Who Saved New York," a 2010 chronicle of New York Gov. Hugh Carey and the 1975 NYC fiscal crisis (winner of the Empire State History Book Award).

Tubridy is a researcher, editor, and freelance writer whose work has appeared in Irish America, The Recorder, and Kirkus Reviews, among other publications. With Irish roots on both sides of his family, he writes and lectures on Irish and Irish American literature, film, and history. His blog is called "A Boat Against the Current."