There is much to be grateful for, so I continue to muster fortitude in navigating through this maze called “life.” I now think it's in my blood! How fortunate am I, musing at will, the luxury and privilege of having been born when and where I was. I think of my ancestors, who they were; what they loved; what their time on earth brought them, how they suffered and knew joy; and am reminded of a powerful scene from the movie, “Amistad.” A harried and aging John Quincy Adams played by Anthony Hopkins, troubled by current events and in doubt of his power to persuade, argues a monumental case regarding the slave trade before the Supreme Court. Gazing at a bust of his father, John Adams, he remembers what his African friend, Dembe, told him. “In troubled times – reach back to one’s ancestors for strength and courage.”

Adams feels it, the connection, the power, and he whispers, “We've come to understand that who we are is who we were.” I've come to believe that a life can be robbed in all sorts of ways that leave one alive yet not truly living; and that it can also recreate itself. Complications are inevitable, to overcome or give into. I am because “she” was.

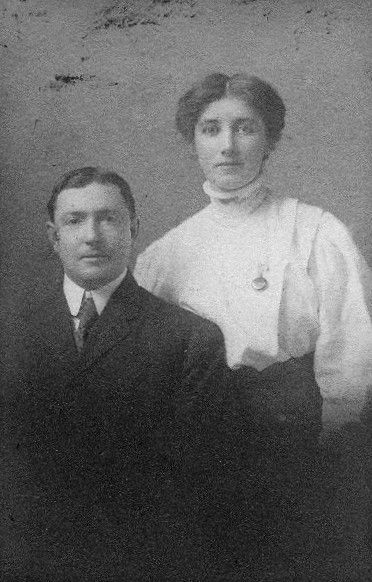

“She” is my grandmother. One of eight children, Margaret Lyons Callahan was born in the village of Kanturk, Co. Cork, Ireland, on Aug. 6, 1883. John Lyons, her father, owned 1,000 acres of farm and grazing land and bought and sold horses. Through family storytelling and photographs, I see my grandmother's depiction – dignified, beautiful, a chiseled face, strong yet graceful. She was known as “Beauty Lyons.” With six daughters, John was used to “gentlemen callers,” and could often be heard blustering, “Now, who's this blaguard coming up the road after one of me girls?” This started early in the life of my grandmother, for when she was just an infant, lying in her cradle, it wasn’t a “blaguard,” but a third cousin to her father, one strapping 18-year-old Daniel Francis Callahan, came visiting one day. The story is told that Daniel took one look at little Maggie and exclaimed, “John, she's the most beautiful creature I've ever seen. Save her for me!” In today's modern world with more enlightened thinking, this sounds quite dreadful. But in those times arranged marriages were not uncommon. The baby’s daughter, my mother, would be born in 1916, still years away from women having the right to vote and to start taking their lives into their own keeping.

Maggie would go on to become an accomplished equestrian, focusing her energy and passion on horses, perhaps in some denial that her fate was sealed. Wrestling through her teen years with an uncertain and unchosen future must surely have been excruciatingly painful. Yet even through all her internal conflict she couldn't help but live and feel her heart, falling in love with a school teacher from her village. How struck with an unbearable grief she must have been, knowing she was destined for another life. In a moment of anguish, she must have thought she could hide from it all, for it is told that she left home for a period of time, living in Dublin and playing her mandolin on the street corner for coins. Her rebellion against the norms of the times, her courage and strength to break away, if only temporarily, speaks of a bravery and warrior-like determination to be heard, to “not go quietly”! Alas, she could not escape the reality that she was “promised” to a man 17 years her senior; who came and went and came and went again to America to make his way, a bit of a dandy, waiting across the ocean with assurance that she would join him, one day soon.

It came to pass that at the age of 18, Maggie boarded a steamship, alone, bound for Boston to marry a man she hardly knew, a man she did not love. In my wildest storytelling, words fail me to accurately describe the emotions she must have struggled with the gripping fear, fear of the inevitable and of the unknown. Maggie and Daniel were married in 1905 and rented a house in Beachmont, a part of Revere, just outside Boston. All but two of their eight children were born there; they lost a boy to childhood illness. In the 1920s they purchased a house on Shermer Road in West Roxbury. By the time I knew of them, and I knew them only a little, they had lived most of their lives in this house, Gramma in her 80s and Papa in his 90s. Gramma was terribly arthritic, her thickly stockinged legs, bowled out under her aproned skirt. I can see her slowly walking the length of her long backyard, resplendent with flowers, roses her favorite. Mumma and I'd visit, sitting under the apple tree, sipping tea, seated around an old metal table. I'd be encouraged to go around front and visit with Papa, finding him seated in a rocking chair on the stoop, his legs blanketed, rocking, back and forth, back and forth, a smile on his face, no words. A hand full to times, was I in his presence, maybe two hands' full in Gramma's. Papa was deaf and a bit feeble and needed constant care, so they did little visiting away from home. Gramma was always so serious, quiet, aloof; perhaps she was sad and just so tired. She often held her chin in her hand, as if pondering, her little finger at her lips. Sometimes I would long to hug her, and be hugged, yet there was a reservedness about her that prevented it. In later years, my mother would also write of this in her own memories.

Most every memory I hear of Gramma, is, at least in part, “in shadow.” My sister Pat recalls that shortly after her wedding day, Gramma, on a rare visit to Pat's home, would suggest that she remember “there's only one thing men want.” It unnerved my sister and painted a jaded picture of love and marriage that Gramma perhaps could not let go of. Another time, Gramma uncharacteristically handed me a few dollar bills, pulled out from her sweater sleeve. I felt so awkward and sad, not really understanding why. All I could think to do was to give them back, saying she needed them more than I did. I think now of how it must have hurt her pride, for she was a proud woman. At Papa's wake she was heard asking aloud, more to herself, “Was I mean to him?” Oh my! I'm thankful for what little I know about her life and continue in my aging to return to the thought that in general we don't ask enough questions of our elders, or certainly not in a timely fashion. Was their story only a tainted one? I hope not. I wonder, was there affection, shared true passion in their days together? Had they found a little bit of happiness, a touch of the sacred which sustained them, perhaps in the faces of their children? I hope so.

Gramma died Dec. 23, 1965, having thoroughly cleaned her house, every doilie and linen ironed, folded and put away, absolutely everything in order. My Aunt Elizabeth (Gramma's youngest child) came home to find her lying on the living room couch with a copy of Samuel Butler's Victorian era novel, “The Way of All Flesh,” opened across her chest. In looking up a description of this book's message, I found, “The ability of humanity to overcome both external and internal threats to the realization of its highest personal and social identities.” In my sentimentality, in my love for love, I like to think of Gramma, Maggie, striking in appearance, young and agile, riding into the sun, her hair loose, wind at her back, her favorite horse beneath her, forgetting for just one moment that she was not in charge of her future, and that in that moment, she could feel her highest personal and social identity, immune to any threats, a free woman, totally free, all love, at one with the gallop.