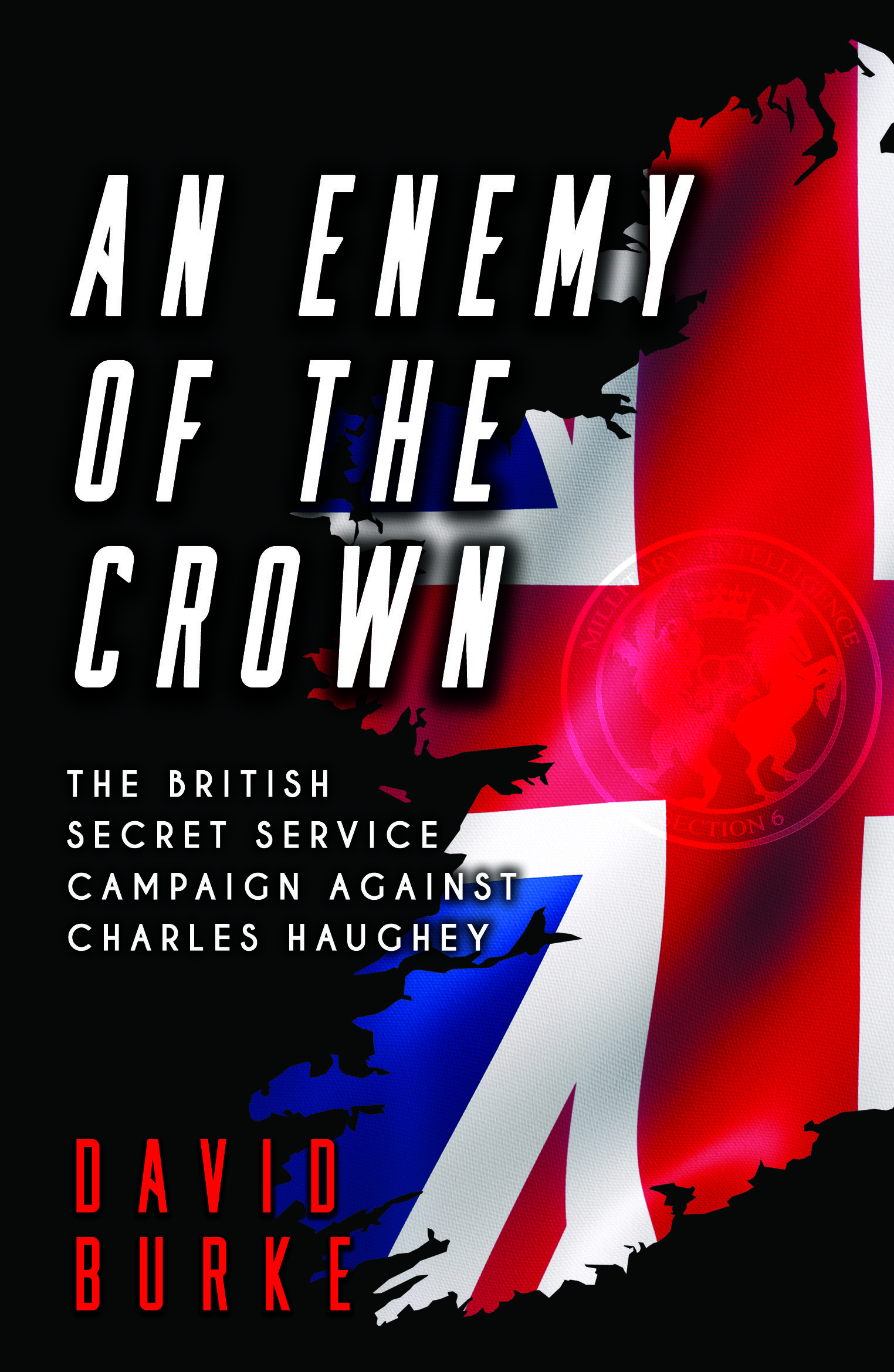

Top British spy Maurice Oldfield’s obsession with one of the most prominent Irish politicians of the 20th century “can be aptly compared to that of Ahab’s fixation with the whale in ‘Moby Dick.’”

So says David Burke in his latest book “An Enemy of the Crown,” which focuses on “a series of plots by the British secret service against Charles Haughey during the 1970s.”

Burke told the Echo, “In 1970, MI6, and others, fed information to the Irish police which led to the infamous Arms Crisis which resulted in Haughey’s expulsion from the Irish Cabinet. Thereafter, the British secret service engaged in an assortment of dirty tricks, including the circulation of smears about Haughey in Ireland, Britain and the U.S. “

The author said, “The aim was to impede Haughey’s bid to secure a position on his party’s front bench and a return to respectability. The operation was a failure for a variety of reasons, not the least of which was MI6’s inability to appreciate the Irish psyche. Haughey became Taoiseach in 1979 and was in and out of office until he retired in 1992.”

Oldfield believed Haughey was a Provisional IRA godfather and set out to deal what he saw as a threat to Britain.

In reality, the future Taoiseach never backed any paramilitary movement, took a hostile stance on the IRA during his rise to prominence and had a complex relationship with militant nationalism generally.

When he made his first bid to be Fianna Fáil party leader and Taoiseach in 1966, a colleague rebuffed his plea for support with the response, “No Charlie, you haven’t got the [republican] background.”

He had the wrong pedigree, in essence: his father, Seán Haughey, had been active in the IRA in Counties Donegal and Derry on behalf of Michael Collins during the War of Independence and Civil War, and following the leader’s death he went south to join the National Army, in which he rose to rank of commandant.

Charles Haughey’s first known political act, at age 19, became part of his legend. It was his leadership role in an incident - after the Allies’ defeat of Germany was announced in May 1945 - that involved the burning of the Irish tricolor and the union jack by respective groups of students from Trinity College and nearby University College Dublin, where he was enrolled. An attempt to breach the walls of Trinity, the breaking of windows in the offices of the Irish Times and a Garda baton charge were also part of the story.

Not long afterwards, a college friend invited him to join the IRA. He declined and told senior government minister Seán Lemass, the father of his girlfriend and future wife Maureen, about the approach.

His own father, of course, would’ve opposed paramilitary activity in opposition to the state; but he would hardly have approved, either, of the perfectly legal path he chose.

The author writes that Seán Haughey “had remained an ardent supporter of Michael Collins throughout his life, while maintaining an aversion to de Valera and Fianna Fáil. Whether coincidence or not, Charles Haughey did not become active in Fianna Fail until after his father’s death [in January 1947].”

The author argues that Haughey’s view on such matters is probably best seen in a Dáil speech in 1958 in which he suggested that the Irish army’s reserve force, the FCA, offered “young men from the ages of 17 to 20…an opportunity of being inculcated with patriotism, proper national ideals, a sense of patriotism and all the other advantages that go with military training at the early age.”

Said Haughey, who himself had youthful training in the army’s World War II-era Local Defence Force, “A lot of young men who find themselves caught up in movements without realizing fully what is involved in the ultimate would never get into these difficulties if the career of a member of the FCA were made more attractive and interesting.”

He had been elected to the Dáil for the first time the previous year in a general election campaign in which Fianna Fáil was returned to power promising to take a firm hand with the IRA, then conducting the Border Campaign.

It introduced internment, but changed course when an IRA member took a human rights action, and it instead enacted new special powers, involving special courts that imposed long custodial sentences. Haughey was centrally involved from 1960 as a junior minister and soon afterwards as Minister for Justice, in a government now led by Lemass, his father-in-law, who'd taken over the reins of leadership from de Valera.

The defeat of the Border Campaign – the IRA quit in February 1962 – was in the words of a leading civil servant “a great personal triumph” for Haughey.

The Taoiseach entrusted his son-in-law with bridge-building trips to Belfast ahead of his own historic meeting with Prime Minister Terence O’Neill in 1965. The author says that Lemass was able to rely on as a conversational icebreaker the personal ties between Haughey and senior unionist minister Brian Faulkner, a fellow equestrian enthusiast.

When Lemass resigned in 1966, Haughey discovered that being married in didn’t count as pedigree. It was the equally ambitious Neil Blaney, whose father was on the opposite side in the Civil War in Donegal to Seán Haughey, who delivered the bad news.

But circumstances in Northern Ireland would make the man who got the job, Jack Lynch, be seen as a moderate, opposed by Blaney and Haughey, and a third senior minister Kevin Boland.

In 1969, the British diplomatic and intelligence communities viewed Haughey as “more passionate” about the ideal of Irish unity than many of his Cabinet colleagues; the Arms Crisis of the following year, however, had him re-labelled an “extremist,” along with Blaney, who’d been fired with him, and Boland, who’d resigned in protest.

If Fianna Fáil experienced a degree of turmoil during at the onset of the Troubles, the effect on the republican movement was far more profound: it split between the Officials, a Marxist faction whose leaders were mostly committed to winding down the IRA, and the more traditionalist and militant Provisionals.

The Officials argued that the Provisionals had been created by elements in Fianna Fáil. Some in the media and in the Dublin and London governments believed this story, too, or some version of it.

Blaney was eventually expelled, and confined to his own bailiwick in Donegal, while Boland formed a new party that flopped. That left Haughey – for Oldfield, at least, who didn’t understand the intricacies of Irish politics – as the last extremist standing within Fianna Fáil.

Burke, who wrote an essay about “Enemy of the Crown” in the March 15-21 issue of the Irish Echo, is a contributor to the Village Magazine and other Dublin-based periodicals. He is also the proprietor of the just-launched online Covert History Ireland magazine.

David Burke

Date of birth: June 8, 1964

Place of birth: Dublin

Spouse: Catherine Neville

Children: Robert and Alison

Residence: Dublin

Published works: “Deception and Lies, the Hidden History of the Arms Crisis 1970” (2020); “Kitson’s Irish War: Mastermind of the Dirty War in Ireland” (2021); “An Enemy of the Crown, the British Secret Service campaign against Charles Haughey” (2022).

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

Late at night when the phones stop ringing.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

I write about events which straddle the border between current affairs and modern history. In this field, it is essential to talk to the people who lived through the events you describe. Records are all very fine, but you can’t converse with paper. You can guess at what is written between the lines of a document, but with a living soul, you can dig deeper to get to the heart of an issue. When a witness opens up, you can sometimes extract the truth from the jaws of oblivion.

Being able to relate to people can be as important as writing skills.

You should inquire into issues that interest you.

There will be a few Eureka moments along the way to render the effort worthwhile.

Get to the point – quickly, or at least as early as possible in your work.

No matter how good you are, you will start out as an unknown. So, hang onto the day job if you have one.

Oh, and if you are writing a book ……. finish a full draft before you tell anyone about it!

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

“The Day of the Jackal” by Freddie Forsyth; “The Unforgiven: The Story of Don “Revie’s Leeds United” by Rob Bagchi; “Life” by Keith Richards.

What book are you currently reading?

“Mary Lou McDonald: A Republican Riddle” by Shane Ross.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

“The Honorable Schoolboy” by John le Carre.

Name a book that you were pleasantly surprised by.

"The Magus” by John Fowles.

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

John le Carre.

What book changed your life?

“War and an Irish Town” by Eamonn McCann.

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

Dalkey Bay, Dublin.

You're Irish if...

You can make friends with strangers if they interest you.