When the members of Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly gathered on July 1, 1998, it wasn’t the DUP or Sinn Féin that challenged the new system first.

Instead, it was Monica McWilliams, elected for South Belfast on the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition ticket, who did, by signing her designation as “nationalist, unionist and other.” Her party colleague Jane Morrice, of North Down, did the same.

They were supposed to choose just one. Their problem, however, was “other” on its own failed to capture that their party had won second-, third- and lower-preference votes across the board – not least in working-class loyalist and republican neighborhoods – in addition to their first-preference votes.

After an adjournment it was agreed that they could use the term “Inclusive Others.”

McWilliams, a Catholic academic originally from Kilrea, Co. Derry, and Pearl Sagar, a Protestant community activist from East Belfast, founded the party after approaches to other parties about women’s participation had fallen short of what they felt was required at a minimum.

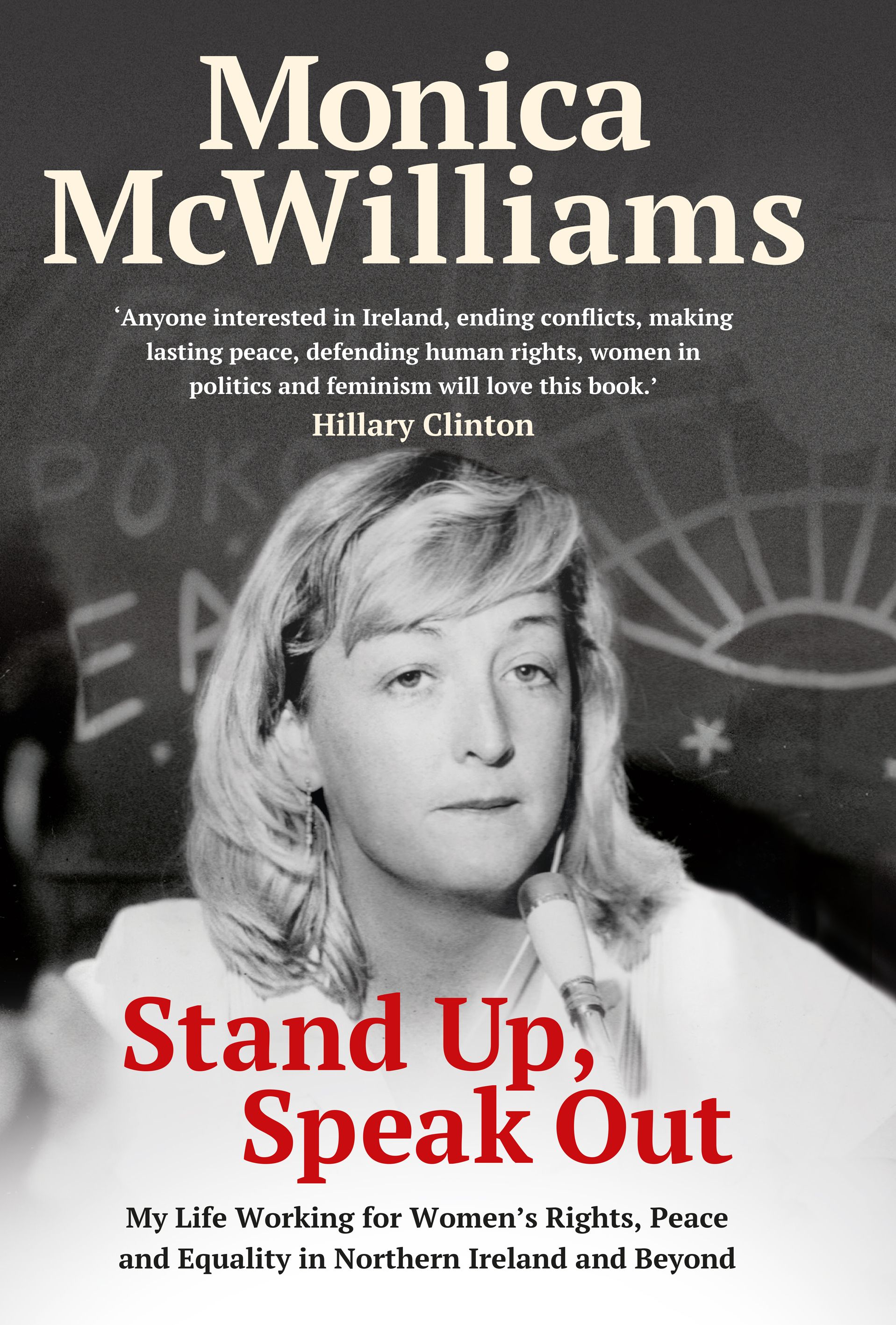

While the Women’s Coalition challenge to the “macho politics of Northern Ireland” ruffled quite a few feathers and attracted a sexist backlash, McWilliams’s autobiography “Stand Up, Speak Out” reveals that she forged close working relationships with individuals in other parties. One such was Sinn Féin’s Pat Doherty, whose wife Mary had been a student of hers; another was the late Ulster Unionist politician James Leslie, whom she describes as “one of life’s gentlemen.”

And, in dealing with crisis after crisis, a particularly close bond was formed with David Ervine of the Progressive Unionist Party, which was aligned with the UVF. She and her husband, Brian, a native of West Belfast, became firm friends with Ervine and his wife, Jeanette. The couples became aware of a rumor that the two politicians were having an affair, and they felt the best way to deal with it was to ignore it. The rumor, she says, was “intended to damage me, as invariably it’s the woman’s reputation that’s on the line when these kind of stories circulate.”

McWilliams writes, “David’s East Belfast constituency bordered mine, and we worked together to tackle sectarianism. He was right when he said, ‘I can smell sectarianism a mile off. It doesn’t grow wild in a field; it is tended in a window box.’”

She says later, “Despite numerous death threats, it wasn’t a gunshot that killed David – but it might as well have been. At the age of 53, he died from a heart attack [in January 2007] caused by the stress of trying to make the peace process work."

The title of McWilliams’s book is a slogan, but one formulated as a retort to her being told by an elected representative to sit down and shut up. But she’d long learned to stand up and speak out, before even she was “putting gender on the agenda” in her 20s, as discussed in Chapter 4.

At age 10, the future co-founder of the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition was book-keeping for her cattle-dealer father and dispensing pay-outs in her grandmother’s post office.

“The mantra in our house when I was growing up was that education was the way to better yourself – it was free and it was the ticket to wherever we wanted to go,” writes McWilliams, who was from a family of three girls and two boys (two more girls died at birth). “My parents were determined that we would make the most of the opportunities that were on offer for us that hadn’t been available to them.”

Her mother, Elizabeth, went as far as taking her older brother out of his Catholic school, because she was unhappy with the stream he’d been placed in by the priests, and enrolled him in the Protestant grammar school.

Of course, McWilliams was well aware early on she was growing up in a divided society. She came to know in time of the backdrop of the Troubles of the 1920s when the northern and southern states were formed. Her father Owen’s oldest sister Sadie, a member of Cumann na mBan, married a man who went south to join Michael Collins’s National Army, aka Free State army. His name was Johnny Haughey, and his son Charlie rose to prominence in politics in the Republic. McWilliams’s mother likewise had a cousin, Dan McKenna, who was an IRA commander forced to go south, where he, too, joined the Free State side in the Civil War, and indeed eventually became chief of staff of the army.

As it happens, Charlie Haughey’s father-in-law was Seán Lemass, who’d been imprisoned by the Free State as a young man, but in his 60s was head of government, or Taoiseach, of the Republic and in that capacity went to Belfast to meet the Northern Ireland Prime Minister Terence O’Neill in 1965.

When Haughey, later on Taoiseach himself, was acquitted at the Arms Trial in 1970, a bar belonging to cousins in Coleraine was painted with loyalist slogans, and later sprayed with gunfire. One perpetrator arrested by the police made it clear his motivation was the belief that Haughey had sent guns to the Provisional IRA.

McWilliams writes, “I came across this man many years later and heard him say, ‘It was a very cruel time when morality went out the window.’”

She adds, “It was a miracle that none of us were killed.”

The author says, “By 1970, we were witnessing the emergence of militant republicanism and loyalist paramilitarism. I saw how quickly ethnic and political identities became entrenched.”

She mentions the major points of escalation in the early years of the Troubles: the killing of three teenage soldiers from Scotland, lured to their deaths on a night out in March 1971; the introduction of internment in August 1971, and the revelations of brutal interrogation techniques used on internees; Bloody Sunday; Bloody Friday in Belfast and the Claudy bombing in her own home county.

But the tragedy that hit hardest involved a close friend, a fellow Queen’s University student named Mickey Mallon, who was abducted and killed by the UDA in 1974.

Inspired by the civil rights movement of her youth, McWilliams began to find her own political voice in her early 20s, in feminist groups, in the trade union movement and in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

At a 1978 presentation to an Irish-American group in Detroit about divisions in Belfast, she suggested that they reach across the racial divide and work with African-Americans. Some “looked aghast” at this advice and she wasn’t invited back, but she was asked to talk before the Ad Hoc Congressional Committee on Irish Affairs.

As part of her academic work, McWilliams has authored three books on domestic violence, as well as journal articles, essays and reports on family and sexual matters, and human rights in Northern Ireland.

After McWilliams’s career as an elected representative ended, she was appointed chief commissioner of the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission, which was established by the Good Friday agreement. In that capacity, she worked closely with her counterpart in the Republic, Maurice Manning, a fellow academic and former politician.

Now Emeritus Professor of the Transitional Justice Institute (Ulster University), she also chairs the Governing Board of the international NGO Interpeace and has worked with and for women in conflict societies including in South America and the Middle East.

Monica McWilliams.

Former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has said of “Stand Up, Speak Out,” “Anyone interested in Ireland, ending conflicts, making lasting peace, defending human rights, women in politics and feminism will love this book.”

Former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern praised the book as a “stunning read” and described McWilliams as one of “Ireland’s greatest women activists, who “undoubtedly played one of the most pivotal roles in the Northern Ireland peace process.”

Lyse Doucet, BBC chief international correspondent, has called it “an unmissable memoir of a soaring hope for justice and peace, and of shocking misogyny. Women are so often written out of the history they make; women like Monica McWilliams make their voices heard, with humor and grace.”

Monica McWilliams

Date of birth: April 28, 1954

Place of birth: Kilrea, Co. Derry

Spouse: Brian Smart

Children: Gavin and Rowen Smart

Residence: Belfast.

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

Losing all sense of time as I become totally focused on the story I am writing.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Pass on the stories that could be forgotten by letting the pen and laptop do their work.

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

Any memoirs written by historical figures.

What book are you currently reading?

Helena Kennedy’s “Eve Was Shamed: How British Justice is Failing Women.”

Is there a book you wish you had written?

Colum McCann's “TransAtlantic.”

Name a book that you were pleasantly surprised by.

Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall.”

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

Hilary Mantel.

What book changed your life?

Sheila Cassidy's “Audacity to Believe.”

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

Portstewart, Co. Derry.

You're Irish if...

You love talking politics and enjoy good craic.