“What a life! What a character!”

These were Harry Martin’s thoughts as he listened to Cormac O’Malley speak one evening about his father.

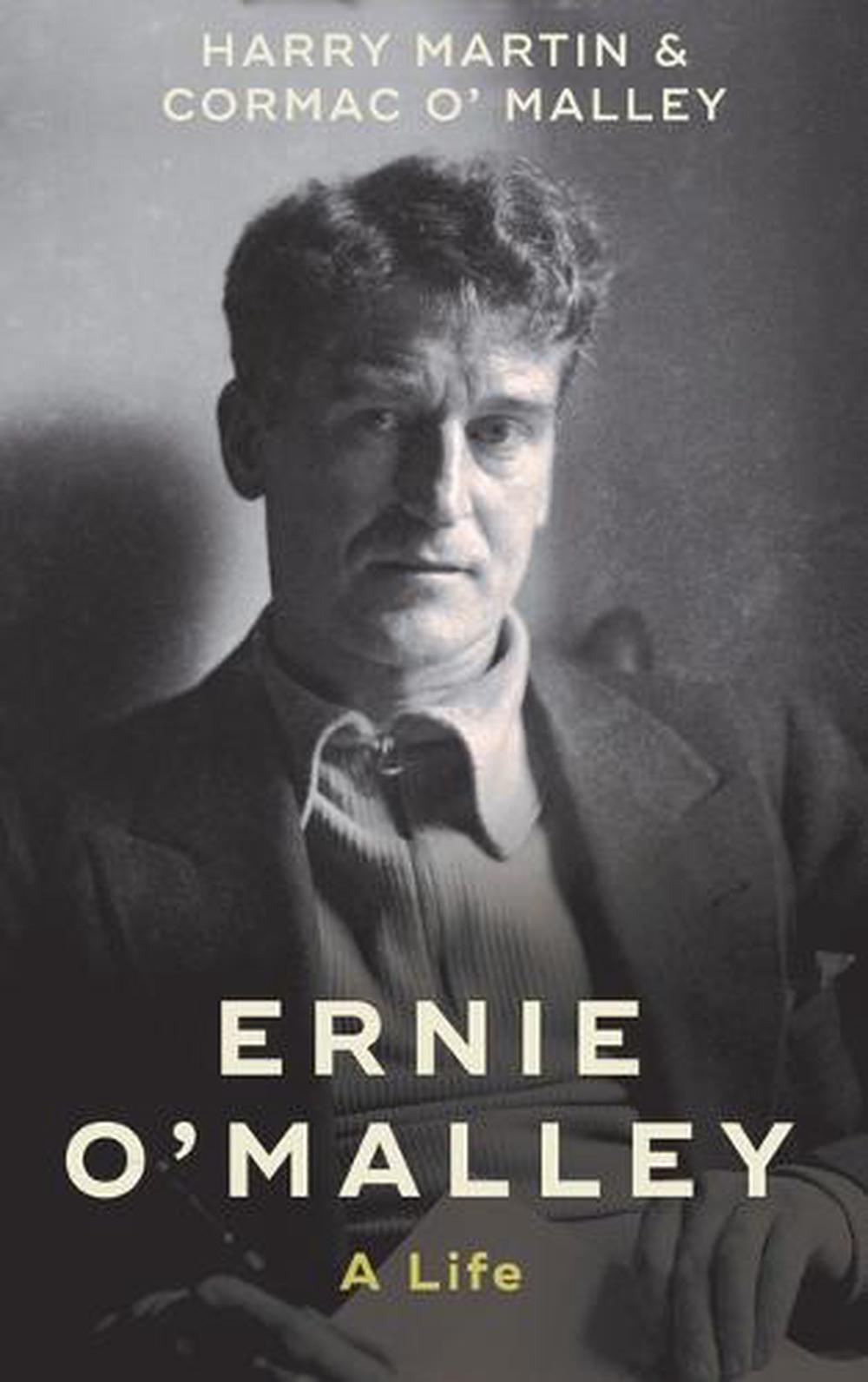

That night was conceived the idea of a new biography of Ernie O’Malley, who became a full-time IRA organizer at the outset of the Irish War of Independence and was a leading fighter against the first Irish government during the Civil War and member of the Dáil.

O’Malley was an international traveler, a patron of the arts, and writer of memoirs of the two conflicts he participated in, both acclaimed for their literary merit.

Martin fell in love with this “Hemingway-type” character.

“Excellent as Richard English’s is, it’s more than 20 years old,” said Martin’s collaborator on the book Cormac O’Malley, about “Ernie O’Malley, IRA Intellectual.”

In any case, that was an academic study by a prominent historian, who himself has praised the new book.

This would be the first conventional biography, telling the story of O’Malley from his birth on May 26, 1897, until his death in Dublin, the city he’d been raised, in 1957. But there have been plenty of other books, with his younger son, Cormac, to the forefront of the effort to the get them into print.

English was among the contributors, too, to the 2018 collection of essays published by Glucksman Ireland House. There have been several thematic works, a collection of radio talks and a biography of a comrade, Sean Connolly.

Ernie O’Malley’s “On Another Man’s Wound” appeared in 1936 in Dublin and London, after being rejected by a dozen publishers during some years spent in the United States.

O’Malley had joined the Irish Volunteers, which would eventually become known as the Irish Republican Army, and was sent out from headquarters to the countryside by Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy.

Eighteen years later, he was sued by Donegal republican politician Joseph O’Doherty about his version of an incident during the War of Independence, and lost. It likely hampered the possibility of getting other books published, and ultimately damaged his marriage, as his spouse, the American sculptor Helen Hooker, would’ve preferred a pragmatic approach to the legal challenge.

Then in 1972, 15 years after his father’s death, Cormac O’Malley received the second volume of memoirs, his account of his struggle in the Civil War, “The Singing Flame.”

It came from New Mexico, where Ernie had been the tutor to the children of a deceased Irish actor; it was sent from one member of that family to another in New York, who in turn knew the writer’s younger son.

“Thank God the U.S. Postal Service works,” Cormac O’Malley said in an interview.

Irish publishers initially balked at the text in its disorganized form and so O’Malley turned to Frances-Mary Blake, an Englishwoman who wasn’t a scholar but was an admirer of his father’s life and work.

“She was able to fill in a lot of the holes,” he said.

Eventually, Dan Nolan owner of the Kerryman, the weekly newspaper based in Tralee, agreed to reissue “On Another Man’s Wound” and publish “The Singing Flame.” It became a trio of books with the publication of “Raids and Rallies.”

O’Malley, said his collaborator Martin was also bringing the perspective of an Irish American to the project and an overview generally of a non-family member.

“We filled in more than Father was writing in his own memoirs. What was happening in the rest of the country at the same time; we had to fill this out and we did that,” O’Malley said, “Other materials were new and not seen by Richard English. All of that added up to having a new look at him.”

In the category of not previously seen is an interview Cormac O’Malley did in 1970 with Seán Lemass, the former Taoiseach, and a comrade of O’Malley’s who escaped capture with him when the Four Courts garrison fell at the outset of the Civil War in the early summer of 1922.

“I asked him the question, ‘Why did they continue?

“We knew we had lost the cause in 1922, but people like your father just kept on,” Lemass told him.

“So you know,” the author continued, “it’s not a great explanation because they could’ve just stopped, but they were loyal to their leaders.”

O’Malley reframed and generalized the question a half-century after the interview on the basis of what’s he’s read in documents: “Surely the leaders should’ve known that they were descending into chaos and why didn’t they stop earlier?”

“It’s not a blame game; well, it’s partially a blame game,” he added.

“Harry’s view is that if Michael Collins had asked Lynch and O’Malley to come to Dublin to have a discussion about a truce, by incorporating them in the decision-making process, they possibly would have possibly gone along with it.

“Now, I disagree with Harry’s conclusion because they were two hotheads that did not have the overview that Collins and Mulcahy had,” he said. “They would not have believed their reports about how few guns there were in Ireland, how little ammunition. They were of the opinion ‘It’s up to us to get the guns’ And ‘no crybabies in my war – you go and steal the guns.’”

Ernest Bernard Malley was the second of 11 children born to Luke and Marion Malley, who were both from Castlebar. His father, a civil servant, transferred the family from Mayo to Dublin when Ernie was a child. The parents stressed the values of education and religious faith. Marion hoped that her second child might become a priest; and despite the hierarchy’s hostility towards the republican side during the Civil War, he remained actively Catholic throughout his life and sent his children to Catholic schools in Ireland and England.

Luke and Marion had pro-establishment and presumably moderately nationalist, pro-Home Rule views, although they were friends with Major John MacBride, a fellow Mayo native who was a visitor to their home in Glasnevin just weeks before his May 1916 execution by firing squad.

Ernie was a first-year medical student at University College Dublin at the time of the Rising, and became drawn into the week’s events.

The biography details a series of episodes before that – for example, in 1911, spelling King George V’s title with a lower case “k” -- that show his turn toward radical nationalism, which was aided by the education at the Christian Brothers school at North Richmond Street.

“He writes very poignantly about his parents’ view of his brothers joining the British army, and he’s quite aware of the guffaw that occurs around the family table about those silly people wearing a green uniform and pretending to be marching [the Irish Volunteers],” his son said. “So, he does not disclose nor does he enter into discussion with the parents in terms of his real attitude.

“[Older brother] Frank is back on sick leave from Romania, and he questions him in a very detailed manner about military maneuvers and it clearly dawns on Frank that he’s dealing with a rebel in 1917 [when he was still at home]. And yet he continues the discussion. He doesn’t turn him in, unlike his father, who turned in a rifle when he discovered it,” Cormac O’Malley said. “If there had been a raid on the house, he would’ve been fired.”

O’Malley spoke of his father’s approach to guerrilla war, and its ethical dimensions, which are shown in the book. “He didn’t shoot every person who’s in uniform, as Dan Breen might have. He was selective about the circumstances in which he would have a fair fight – and sometimes not even shooting at them, letting them go.

“When he does execute three officers, he does that for a very specific reason: several IRA guys had been caught and they were up for execution,” he said.

“If they were executed, he would execute; if they were not, he would not.”

Meantime, his brothers Frank and Albert, the family’s third son, had rejoined regiments of the British forces in the years after the First World War had ended. Albert had been a member of the Connaught Rangers, which was disbanded after members mutinied in India in 1920.

His mother encouraged him to sign up with the British West African Rifles across the Irish Sea in Liverpool, rather than be a target at home in Ireland as a former soldier. He died in Africa in 1921, of blackwater fever, and Frank died there in 1925, of the same disease.

“Cecil, Paddy, Kevin, and Charlie joined the [anti-Treaty] IRA under Father’s influence,” their nephew said.

Charlie O’Malley was killed in the Civil War, on July 4, 1922, the day before he was due to finish his first-year veterinary exams.

Cecil had broken both legs when he jumped from the burning Customs House during the last weeks of the War of Independence.

Paddy, who later became a banker, was on hunger strike for 41 days at age 17. Kevin, at 15, used his wooden leg stump (the bottom of his leg had been amputated in early childhood) to carry messages for the anti-Treaty IRA in 1922.

The youngest son, Dessie O’Malley (he added the “O” as had Charlie, Ernie and their sisters), was a child during these events, and wasn’t fooled when family members addressed a guest as “Jackie.” He took his older brother aside to say: “I know you’re Ernie.”

O’Malley was eventually captured following a shootout in Dublin in which a government soldier was killed. The prisoner was badly wounded. His son has been telling his revolutionary father’s story in “Ernie O’Malley’s Journey,” a month-by-month account available on YouTube, and the relevant episodes reveal, as does the book, how O’Malley attempted to put off a military trial as long as he could, as he believed it would inevitably end in his execution. [For all 54 episodes, go to the YouTube playlist here.]

His mother, who didn’t agree with his views, did everything she could to help. “She was never a republican, but she was there for her son,” Cormac O’Malley said. “She wrote letters to Dick Mulcahy and [minister] Desmond FitzGerald saying they got him involved [in their position as leaders of the independence movement in the post-1916 period].”

He paraphrased her stance, “You got him into this position, not treat him fairly. Get him a doctor, get him restored, do what you’re going to do, but don’t let him die.

“Put him on trial for murdering a soldier, but don’t let him languish in a jail in the manner than you’re doing.”

In one letter to the minister, Marion Malley cited her son’s affection for FitzGerald from their time as comrades. As it happened, Ernie corresponded from prison with his wife, the former Mabel McConnell, who sympathized with the resistance to the Treaty. Her youngest son, future Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald decades later confirmed that his parents disagreed on the issue.

Cormac O’Malley said that Garret, the fourth son, was born in 1926 after a gap of six years since the birth of the third. “You can draw your own conclusions,” he said.

O’Malley was released in 1924, and spent some time traveling in Europe. At the behest of the leader of the political opposition Éamon de Valera, he went to the U.S. in 1928 with Frank Aiken, the IRA chief-of-staff at the end of the Civil War, to help raise funds for a proposed daily newspaper, the Irish Press, which would adhere closely to the line of the Fianna Fáil party.

He continued on his travels after that mission was completed, and traveled widely in the United States and Mexico. During those years, he became friendly with many artists and writers, and along the way he met Helen Hooker, an heiress from Connecticut, who was something of a rebel herself among her sisters, having chosen art college over Vassar.

In an interview for the Seattle Daily Times in 1929, O’Malley left no doubt that he’d transitioned from a military career. “My soul lies with the arts,” he said. “In them lies happiness. I hope to be able to restore Ireland’s interest in them.”

Knowing that he would have a source of income in a military and disability pension at home, he proposed to Helen.

After their marriage in a Catholic church in London in 1935, the couple settled in Ireland, where they would divide their time between a farm in Burrishoole, Co. Mayo, and Dublin.

Ernie rebuilt his relationships with family members. The authors write: “The children supported each other throughout their lives. Their parents had sent deeply motivated, hard-working young people out into the world. Several were blessed with outstanding success, and several survived serious wounds from the wars that consumed Ireland and Britain from 1914 and 1945.”

Three brothers, Cecil, Kevin and Brendan, became distinguished doctors (each was first in his class at University College Dublin Medical School, which Ernie had dropped out of twice). Brendan joined the British Medical Corps as a captain during World War II. He was severely wounded in a Japanese attack near Sri Lanka and spent five years recovering in a British military hospital in Australia. Cecil became the first Catholic to be a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in London; while Kevin did postgraduate work at John Hopkins in Baltimore before becoming a leading heart specialist in Ireland. He cared for Ernie, who had a frail heart from childhood, in his last years.

The authors write: “Ernie’s two sisters, Marion and Kaye, had interesting careers as nurses in London and Dublin. Marion later died, in 1948, when her Irish-born husband crashed their small plane on the French coast after going over the English Channel. He had previously lost an arm flying for the Royal Air Force against Germany.”

Kaye was a captain in the Irish Nursing Corps during World War II and was later a leading member of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association. She lived with her husband in Howth, Co. Dublin, and nursed her ailing brother Ernie there in his final months.

Their mother, Marion, also went to live in that suburb with her son Kevin, “a surgeon and a bachelor with an expense account,” in Cormac O’Malley’s words.

“She’d moved out of the house to the far more prestigious address. She was able to run that place for him,” he said.

She came to look down on Luke (“a stiff old character,” said his grandson).

“He never got to where he should’ve,” O’Malley added, summarizing her view.

Of course, having five sons in the anti-Treaty IRA didn’t help his career in the Free State civil service, which he’d transferred to after independence.

“She was a very independent person,” her grandson said. Marion Malley played bridge with the German ambassador’s wife, went alone on vacation to Biarritz and later befriended a socialist neighbor and his wife in Glasnevin, Peader O’Donnell, the novelist who’d been imprisoned with her son in 1922 and was his editor at the literary magazine the Bell.

Ernie O’Malley led a remarkably active career as intellectual, farmer, critic, folklorist and collector of oral histories of the War of Independence and Civil War (the basis of the series of books “The Men Will Talk to Me,” edited by his younger son).

Above all else, he was a close friend and mentor to leading artists, like Jack Yeats, Evie Hone and Louis la Brocquy, and became a commentator on Irish art in journals and in lectures on Radio Éireann and the BBC.

Film director John Ford, left, with Ernie O'Malley in 1956.

Helen gave birth to Cathal in 1936; a daughter, Etain, in 1940, and finally Cormac in 1942. “Ernie O’Malley: A Life” tells the story in detail of their tumultuous marriage, which disintegrated slowly in the mid- to later 1940s. Both were absent intermittently from the lives of their children during the breakup, but Ernie took care of the boys for two years in Mayo after they caught tuberculosis. Helen thought her children’s health would be improved in the U.S. and that was the pretext for her kidnapping Cathal and Etain at their Irish-language school in County Waterford in March 1950.

Helen obtained a divorce in America, and thereafter Ernie only saw his older son and daughter when they made trips back with her. Cormac, the youngest, would now be the focus and joy of his life.

Though he had no wish for one – the authors say he had no animus against his former opponents in the War of Independence and Civil War – Ernie O’Malley was given a state funeral with full military honors upon his death in March 1957. Taoiseach de Valera, just recently returned to power, and senior ministers Lemass and Aiken were in attendance. Another former anti-Treaty commander and minister, Seán Moylan, gave the graveside oration.

Taoiseach Eamon de Valera, center, with ministers Seán Lemass, left, and Frank Aiken, at Ernie O’Malley’s state funeral.

Cormac, then a 14-year-old student at Ampleforth College, a secondary school in England run by the Benedictine order, went to live with his mother in America.

In 1973, RTE journalist Cathal O’Shannon asked Helen why in 1955, on a trip to Ireland, she asked Ernie to remarry her, despite everything and despite the fact she was traveling with another man she would later marry. She replied, “There was no one like him. I would have done it all over again. To have those years with him was a great privilege to me.”