The great Shakespearean drama "Macbeth" issues a clear warning to power-hungry and unscrupulous leaders about the consequences of their actions. “Things bad begun,” the bard warns “make strong themselves by ill.”

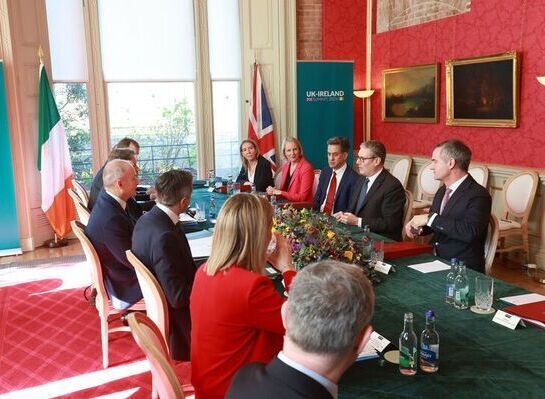

The partition of Ireland got off to a very poor start because not even one nationalist leader was consulted at any stage about truncating the island.

The other community, unionists, led by James Craig and Edward Carson, had veto power over the negotiations in Westminster, but the minority Catholic population in Ulster had no say in the deliberations about the future governing of their country.

Protestants outside of Ulster wondered how their rights would be protected in the promised nationalist parliament in Dublin where they would be a minority, cut off from their northern co-religionists. Originally, the Loyalists demanded a statelet that would include all nine counties of Ulster.

This would leave them vulnerable with only a small voting advantage in the whole province, and Catholics all over Europe had bigger families than Protestants so, looking ahead, Craig feared that they might lose their majority. Thus, the reduction to a statelet with six counties.

English leaders would have far preferred one parliament in Dublin along the lines of the 1914 Home Rule Bill which passed all stages in the House of Commons.

Viewed from their colonial perspective, it would be awkward for Westminster to oversee two governments on a small island. It would also invite calls from Welsh and, especially, Scottish nationalists that would involve radical changes in their territories.

Edward Carson believed that the British leaders were being far too generous in their negotiations with the Sinn Fein leaders during the Treaty deliberations in London. He also resented some of the British negotiators’ persistent prompting that the autonomous Belfast parliament should consider switching its allegiance from Westminster to Dublin. That would have been a real coup for nationalists, but Carson’s vehement veto ensured that the idea never caught on.

The leaders in Westminster saw Edward Carson as someone with steadfast loyalty to the Crown who was certainly preferable to nationalist leaders, driven by achieving some kind of independence for Ireland. Among his own loyalist people, he was hailed as King Carson, the patriarch of Northern Ireland, and an imposing statue of him still greets visitors to the Stormont Buildings.

Edward Carson.

He ranted against “the invasion of Sinn Fein” and his many tribal speeches inflamed his own community. The sectarian violence was stoked by leaders like Carson; almost 500 people, mostly law-abiding Catholics, were killed during the first two years of partition.

In the Treaty negotiations in the fall of 1921 the Irish delegates placed a great deal of emphasis on the Boundary Commission which would decide where the lines would be drawn between the two jurisdictions. It is important to note that the full Sinn Fein cabinet in Dublin grudgingly approved the idea of redrawing the map of Ireland. Michael Collins believed that the counties of Tyrone and Fermanagh, which had nationalist majorities, would be transferred in the negotiations to southern control.

The Boundary Commission turned out to be a damp squib. Emotions ran high when areas with Catholic or Protestant majorities were considered for movement to the other’s jurisdiction. The mood in unionist Belfast could be summed up succinctly as “not an inch. What we have we hold.”

Eoin MacNeill.

Towards the finish of the deliberations, Eoin MacNeill, the Dublin representative on the Commission, resigned in frustration and by December of 1925 the Commission ended its work without geographical changes but with the Irish prime minister, William Cosgrave, having managed to get liberated from burdensome public debt and war pensions payments agreed to in the 1921 Treaty.

Historians speculate about how the Boundary negotiations would have developed if Michael Collins had lived. Unquestionably, he was very concerned about the pogroms in Catholic areas in the North, and he continued sending men and money to Belfast when he headed the new Irish government in 1922. Would he somehow have succeeded in prizing Tyrone and Fermanagh away from the northern statelet? Even if he had succeeded that would leave the nationalists in the remaining four counties even more vulnerable.

Partition recently passed the 100-year marker, and even unionists concede that it has led to all kinds of instability.

The minority nationalist community faced blatant prejudice in employment, housing and policing. As the late unionist leader David Trimble put it when accepting the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo with John Hume in December, 1998: “Ulster unionists, fearful of being isolated on the island, built a solid house, but it was a cold house for Catholics.”

The core issue separating the two communities remains the division of the country. The vast majority of nationalists want the British out while an equivalent percentage of loyalists desire the maintenance of the Westminster connection. A recent opinion poll, the LucidTalk survey for the Sunday Times, reveals that 48% of those questioned favor maintaining the status quo with Britain continuing to call the shots. A united Ireland was approved by 41% with the remaining 11% unsure.

Interestingly, 57% of 18 to 24-year-olds would vote for Irish unity today with just 35% favoring the current arrangement. It is fair to conclude that we are very likely in the closing years of a partitioned country.

William "W.T." Cosgrave.

Republicans and nationalists show no desire to follow the example of unionists in 1920. The late Seamus Mallon, considered the hardline nationalist voice in the Social Democratic and Labor Party, proposed that no new arrangements should be attempted on the constitutional issue until two-thirds of the northern population wants it. A number of thinkers on the nationalist side stress that 50.1% voting for unity should not be seen as a mandate for change.

They certainly have a point about the limits of simple majoritarianism as a springboard for change. However, if any number over 50% opts for unity in a referendum, the game will be seen as over by both sides.

A spirit of magnanimity was evident in a speech a few months ago by the Sinn Fein leader, Mary Lou McDonald, who said that she would like to see a public holiday on the 12th of July when Protestants celebrate in jubilant and often sectarian fashion the victory of William over James in the Battle of the Boyne.

Involving broad swathes of nationalist and unionist opinion in a wide-ranging discussion about the principles that should undergird a new government for the whole island, and where all traditions would be respected, seems to be a sensible way forward.