People around the world know the searing images Monaghan-born Daniel McGovern captured with his camera in the wake of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, but few know the story of the photographer who saved them for posterity.

The son of a Royal Irish Constabulary sergeant, McGovern was born in Monaghan town in 1909, but raised in Carrickmacross, where he saw the bloody fighting in the Irish War of Independence up close. He also witnessed bloodshed resulting from the partition of Ireland before his family emigrated to the United States in 1922. Growing up to be a six-foot five-inch giant, he was nicknamed Big Mack. McGovern joined the air force and ended up in serving in the First Motion Picture Unit. A photographer for President Roosevelt before setting up an air force camera training school in Hollywood, where McGovern got to know Ronald Reagan, Clark Gable and other Hollywood stars.

McGovern flew bombing missions over Germany – surviving two crashes – and filmed footage used in a 1944 documentary, “The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress.” In 1998, when Steven Spielberg's World War II-set film "Saving Private Ryan" was released, the 88-year-old McGovern told the Los Angeles Times: "Combat men don't like to talk about what they did. Airplanes crashing, headless bodies with helmets still on. Limbs here, limbs there. You say, 'There but for the grace of God,' but you don't talk about it. You relive it in your sleep. You go through recollections of pulling bodies out of airplanes -- an experience you never forget."

McGovern and several of his colleagues founded the International Combat Camera Association to give credit to the cameramen who risk their lives to shoot combat footage.

His greatest legacy would come in Japan at the end of the war, when he took the now famous still photographs of the devastation caused by the atomic bomb, filming it with 35mm in black and white and Technicolor. The fields around Nagasaki were bleached white and the city looked as if a “massive anvil” had flattened it, he later recalled. At a ruined school McGovern photographed the bodies of children amid piles of skulls. “Hundreds of kids had been sucked out through the windows. We were always finding bones, “ he said. He photographed the ghastly scenes at the city’s hospitals, including the agony of a 16-year-old boy named Sumiteru Taniguchi. “His whole back just looked like a bowl of bubbling tomatoes.”

Other patients had rashes, hair loss and bleeding from the nose and mouth – a mysterious malady later identified as radiation sickness. McGovern also photographed the phenomenon of people who had been atomized, yet still left shadows on walls from the bomb’s radiation. The two atomic bombs are estimated to have killed more than 200,000 people.

McGovern’s photographers also filmed 100,000 feet of color film and enlisted the help of a Japanese newsreel service, Nippon Eigasha, which had 26,000 ft of black-and-white footage, much shot before the Americans had arrived. McGovern edited the Japanese footage into a documentary called “Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” and planned to turn the color film into another one.

Washington, though, had other ideas and classified his images as secret in 1946. “They didn’t want the American public seeing the horrors,” McGovern said. He discreetly made copies at the Pentagon. Back in the U.S., he saved the footage from suppression by making secret copies, storing one set at an air force motion picture depository in Dayton, Ohio, and keeping another set himself. After World War II, Col. McGovern wrote, directed, and produced classified films on nuclear weapons testing and development at Lookout Mountain, a secret government film lab and studio built underground in the Hollywood hills of Los Angeles.

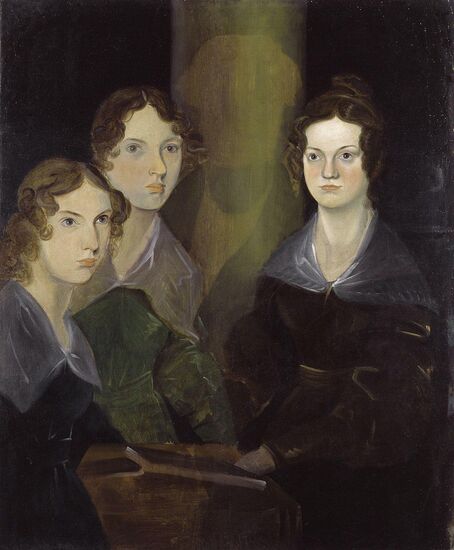

Lt. Daniel McGovern at ground zero in Nagasaki on Sept. 9, 1945. U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES

For 20 years no one saw McGovern’s dramatic footage. Then in 1967 a U.S. Congressional committee that included Robert Kennedy asked to see the atomic bomb footage. The material had been declassified but the originals couldn't be located. Lt. Col. McGovern showed the committee his copies. Finally, In 1970, Americans got their first glimpses of some of the footage, when it was incorporated into a film called Hiroshima “Nagasaki – August 1945” that premiered at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The auditorium was packed. At the end, no one made a sound.

This year, Monaghan journalist Joe McCabe published a biography of McGovern "Rebels to Reels," which includes interviews with McGovern before his death 17 years ago.

“He was the most interesting person I ever met,” McCabe said. "The footage was suppressed for decades and we owe a great debt of gratitude to Dan McGovern that he helped to save it.”

A plaque in McGovern’s honor was recently unveiled next to the former RIC station, now a Garda station, where the family lived during their time in Carrickmacross.

McGovern, whose images of the horror of war remain some of the most powerful photographs ever taken, died on Dec. 20, 2005 at age 96. His wife of 62 years predeceased him in March of that year. His survivors included his four children, a sister, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.