A hundred years ago, combatants began reckoning with the damage done by the Battle of the Four Courts in Dublin, identified as the beginning of the Irish Civil War.

With a century of distance, the violence that tore families and friends apart is less painful – almost forgotten – even with Sinn Féin’s dream of a united country coming back.

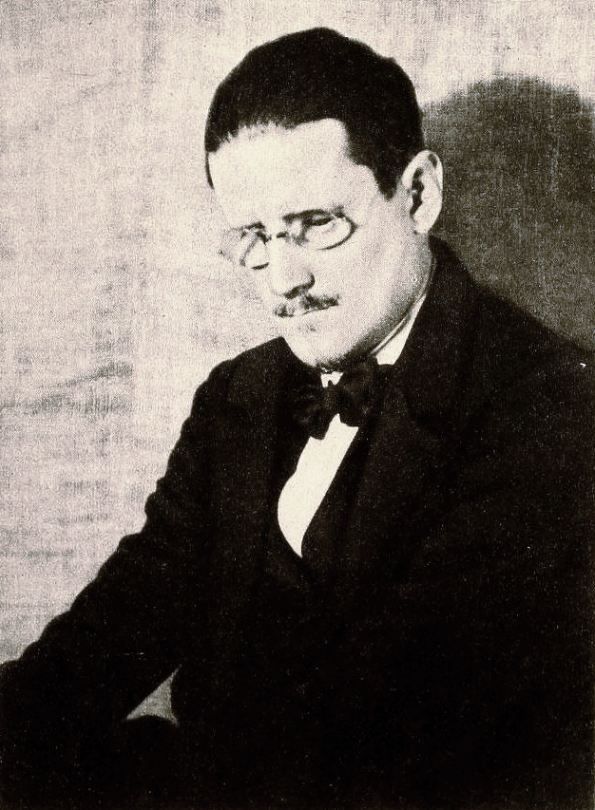

Some weeks ago, the literary world remembered writer James Joyce and his pioneering novel. A more pleasurable affair, for sure, and easier to sell.

All manner of fans, actors, and scholars were out in force on Dublin streets – and in the United States -- celebrating the “Ulysses” centenary.

James Joyce. Photo by Man Ray.

These two landmark events from 1922, political and literary, had largely been disassociated for many years.

They’re being considered together now, more and more. And I can’t do otherwise. A deep examination of the life of my grandfather, C.P. Curran – a friend and contemporary of Joyce in Dublin a century ago -- opened my eyes to the inextricable links, for him, between the Civil War and the campaign to recognize Joyce.

When I first surveyed my family papers, it looked like the jumble of a book lover. Yet, as I made my way through folder after folder, I sensed a purpose. More than holding onto what he cherished, my grandfather was placing papers in safe keeping as a public service; his own, and just as importantly, those of many others.

He aimed to contribute to a historical record, protecting what had been devalued, and defending what was yet to be acknowledged as significant. The 700-year run of documents in the Irish Public Record Office jeopardized by the Civil War was one of his major commitments; Joyce’s writing another. These were two sides of Irish culture he was intent on securing in their hometown.

Curran had entered what had been the British Crown legal service to become the first Registrar of the courts of the fledgling Irish Free State.

In the spring of 1922 he was confronted there with an intense stand-off, pitting those who supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty establishing an independent Ireland, against those who deemed the treaty a betrayal of their Republican ideal.

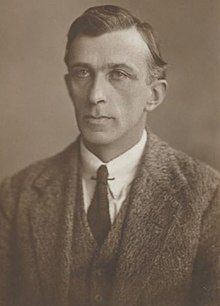

Rory O’Connor.

Curran knew men on both sides: Michael Collins, a friend from the War of Independence days, and chair of the provisional Irish government, and Rory O’Connor, a school chum, member of the Anti-Treaty army executive who occupied and mined the Four Courts, turning them into the first explosive battlefield of the war.

Curran was one rare insider from the courts who sounded the alarm over the fate of the Public Record Office housed there. He wrote to the warring parties, including Éamon de Valera, leader of the Anti-Treaty side, warning them not to endanger this longest record of Irish history.

He made a final plea in person to O’Connor. When the Public Records Office was blown up, his warning disregarded, he took it personally.

In my grandfather’s papers, I discovered how and why he was affected by this destruction. Tucked away, still folded up in its envelope, was the Provisional Government pass authorizing him to go into the bombed site on July 11 to assess the damage.

Of all his personal effects, he held onto this dirty page. A bittersweet memento. His various attempts to convince O’Connor and others not to fight in the PRO had failed. In the end, Collins called on him to inspect the masses of obliterated documents – one of the first to witness and draw attention to the cultural loss. Losing friends on both sides was devastating; losing an outstanding record of history was, for him, incalculable.

Curran was also keenly aware of the importance of letters that his college friend Joyce sent him: the desperate and hilarious note from the summer of 1904; the bulletins reporting on progress on “Ulysses,” from Zurich and Paris during the subsequent war-ridden years.

My grandfather had organized them with care, concerned that they be kept. His affection for Joyce’s writing came right off the musty, faded pages for me. I remember how insistent he was that something of Joyce’s early work stay in Ireland and not go into exile in a private institution abroad, far away from his and Joyce’s Dublin.

Even today, with our sense of place so mobile in our digital world, his view of the significance of keeping Joyce papers in Dublin for the public continues to make good sense. What he never talked about with me, the teenager, was his life-long dedication to organizing this literary record with others.

As Ireland goes through its final, challenging phase of centenaries, remembering the consequences of civil war with Joyce is an ongoing debate.

The launch of the Virtual Record Treasury, reassembling what was lost in the PRO, adds to this debate yet does not resolve it once and for all.

That’s why I’ll keep in mind the quiet, indefatigable work of my grandfather and his advocating for culture.

After all the talk and the fighting, placing all manner of record in safe keeping for the public is the way to ensure that we can better understand the choices people make and their destructive actions alongside their remarkably creative ones.

Helen Solterer is professor of French and Francophone Studies at Duke University. She is the co-editor with Alice Ryan of “James Joyce Remembered,” edition 2022. A Guggenheim fellow, she also edited with Vincent Joos, “Migrants Shaping Europe, Past and Present,” out this fall.