Two court cases from 1890 remind us that the current heated opposition to public health mandates has a long history in the United States, as does the fight to eradicate highly infectious diseases.

Today it is Covid-19, then it was smallpox when a young Irish woman alleged that the British steamship giant, Cunard, vaccinated her against her will.

Mary E. O’Brien sailed with her widowed father, Charles, and five-year-old brother Alfonsis from Cobh (then Queenstown) for Boston on the Catalonia in the summer of 1889.

She travelled in third class with up to four hundred others. Shortly before disembarking on July 15th, two hundred women received the smallpox vaccine from the ship’s doctor.

In an April 1890 court filing, O’Brien claimed that she suffered from “blood poisoning, sores, and humors” as a result. “The virus was vile,” she alleged, meaning that it was contaminated.

She also declared that the vaccine had been administered without her permission or that of her father. The Catalonia manifest lists her age as eleven, although the trial record states she was seventeen at the time she was inoculated.

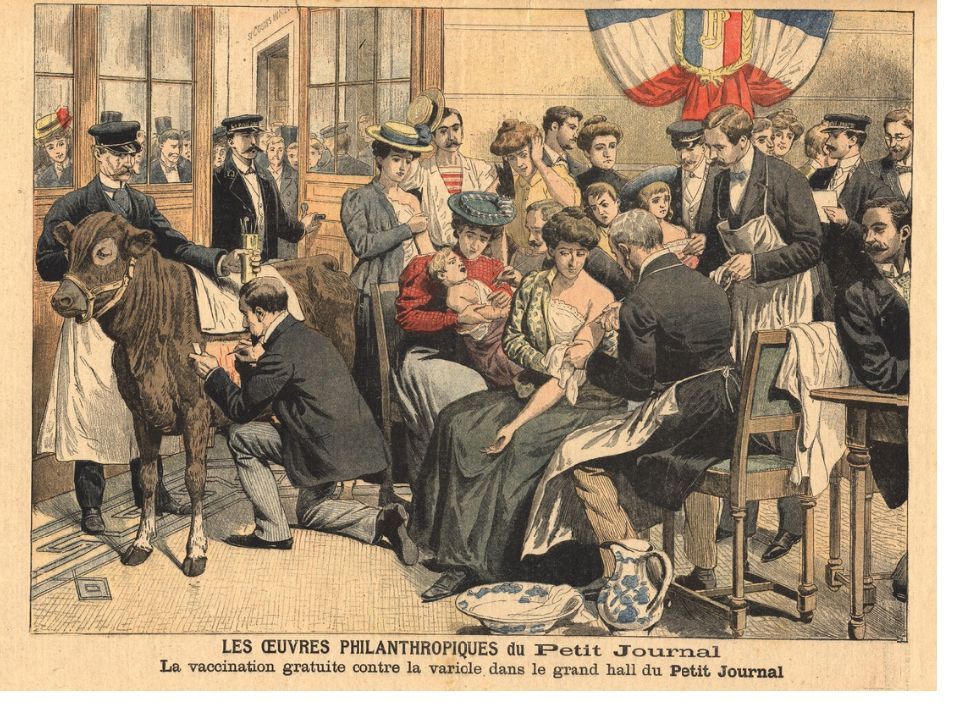

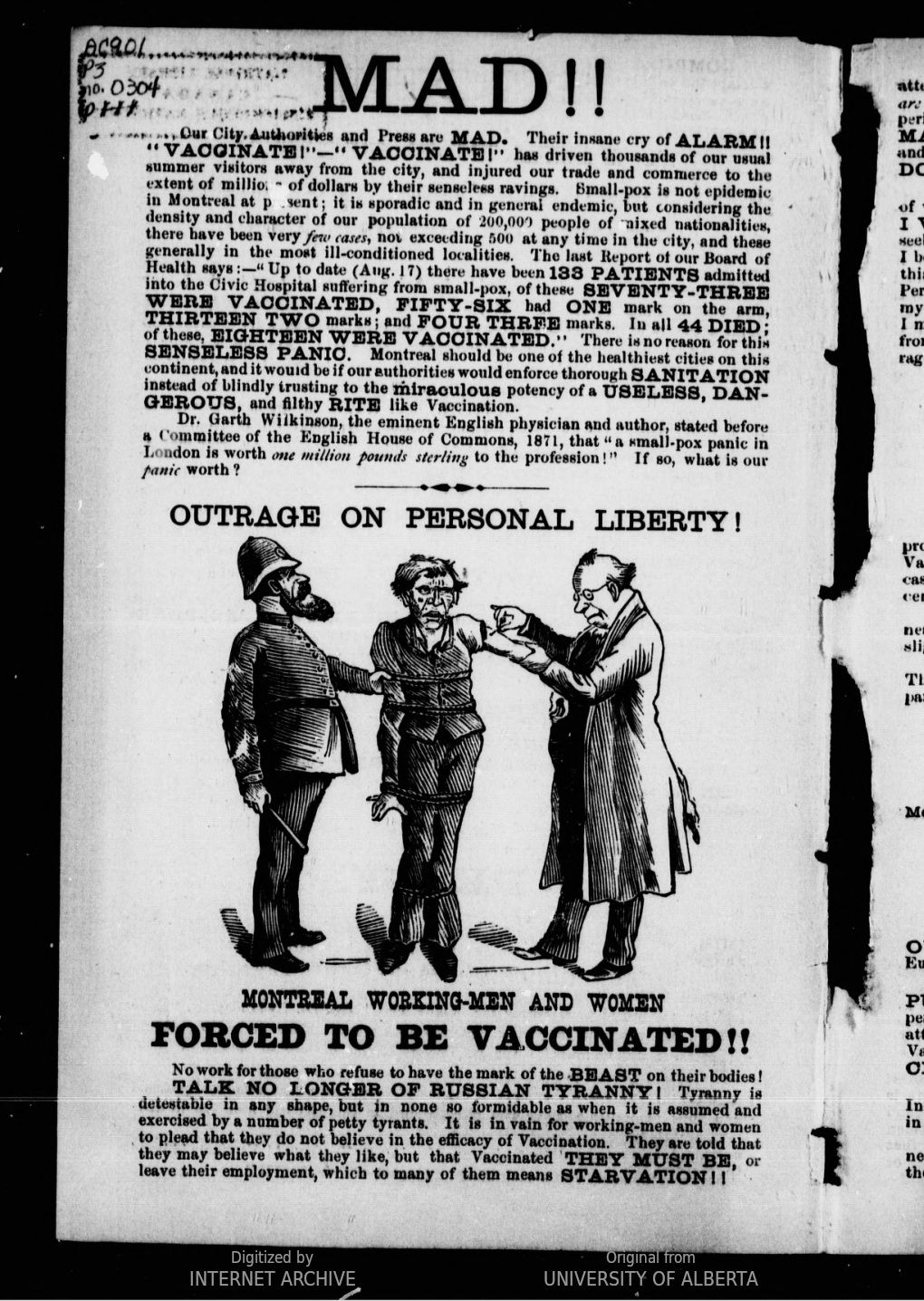

A page from a Canadian pamphlet published circa 1885.

Massachusetts had required vaccinations since 1855 but that decision was not without controversy. Anti-vaccine advocates argued that compulsory inoculation infringed on personal civil liberties, or that the science behind it was faulty, at a time when there was no quality control for the calf lymph used to make the smallpox vaccine.

Boston emerged as the epicenter of the American anti-vaccine movement. In "The Anti-Vaccine Heresy," Karen Walloch calls its supporters “not antigovernment libertarians, but instead thoughtful people who posed legitimate questions about state interference in individual health matters.” They were not, she writes, “cranks, crazy, or the lunatic fringe.”

Perhaps Mary O’Brien’s attorney, Frederic Cunningham, a native of Cohasset who specialized in admiralty (maritime) law, was among these concerned citizens.

Why he took her case is unknown, but it certainly was a novel opportunity to bring together contemporary legal issues – mandatory vaccination and medical restrictions for immigrants – under the guise of corporate overreach. According to the Boston Herald, O’Brien’s case was one of a number that had recently been brought against steamship companies in other cities and that “several anti-vaccinationists” were in court to hear the judge’s ruling.

Mary O’Brien testified that she told the Catalonia’s doctor that she had already been vaccinated for smallpox and “did not care to have it done again.” Indeed, every child born in Ireland after January 1, 1864 was required to be vaccinated against smallpox, a communicable disease that, on average, caused the deaths of three out of every ten infected and horribly disfigured many survivors.

Although there was a high degree of compliance with that law, it appears that many of the Catalonia’s passengers were still unvaccinated as they sailed into Boston harbor.

When the ship’s doctor, James Thomas Moore Giffen, examined O’Brien’s arm to look for the tell-tale pox mark left by the vaccine, he couldn’t be sure of her status.

Without enquiring further about her medical history, Giffen did not offer O’Brien any alternatives if she wanted a landing certificate.

“She, being a modest, retiring girl, did not continue her protest. She was frightened into remaining silent and was vaccinated before she had recovered sufficiently to renew her refusal: she submitted, but did not consent,” Cunningham told reporters.

His client alleged that she had been assaulted as well as injected with “impure virus,” hence her lawsuit for $10,000, the modern equivalent of $1.7 million.

Cunard defended itself by pointing to the qualifications of all the surgeons it hired and assuring the court that it purchased medical supplies from reputable sources.

The company agent in Boston, Alexander Martin, also gave a statement to the Herald.

“The quarantine authorities require the vaccination of all immigrants, and the steamship company also considers it advisable for its own protection and that of the other passengers. So, if a passenger has no mark showing recent vaccination, we offer to perform the operation for him; but he is not compelled to allow the ship’s surgeon to do it, and, if he refuses, it will be done by the port physicians before he is allowed to land.”

Left unspoken was the cost-benefit analysis. Inoculating passengers was cheaper for Cunard than having to cover a fourteen-day quarantine or passage back to Ireland. Free vaccination on board also appealed to poor passengers who otherwise would have to pay the port physician twenty-five cents for it.

Judge Hamilton Barclay Staples found in favor of Cunard, determining that the company was not liable for physician malpractice. Cunningham immediately appealed.

When Mary O’Brien went to court again in January 1891, the alleged grounds were assault, this time compounded by medical negligence. The description of her physical suffering – including blisters “almost over her whole body” and ulceration on her arm at the injection site – were entered into evidence.

Eight doctors testified this time, including the Catalonia’s surgeon and Mary’s own regular physician, a surprising number of “experts” for a case involving an Irish steerage passenger, as law professor Richard W. Bourne points out in a 1992 collection of essays on O’Brien v. Cunard S.S. Co.

Only one of those medical men concluded that it was possibly more than the expected reaction known as “vaccine disease.” Dr. Henry G. Clark, who had seen O’Brien when she was symptomatic, believed the blisters were unrelated to the vaccine and probably pemphigus, an autoimmune disease. In September 1891, the court again sided with Cunard.

Because federal law had required ships of the Catalonia’s size to provide a medical practitioner on board since 1882, and because state law required steerage passengers to have certificates of vaccination before they entered Boston, Judge Marcus Perrin Knowlton reasoned that Cunard was not guilty of assaulting Mary O’Brien.

Not only was the company merely following the law, but the surgeon was not Cunard’s “servant, engaged in their business, and subject to their control as to his mode of treatment.” His sole relationship was with his patients as far as the company was concerned.

Knowlton did not consider whether O’Brien was intimidated by Dr. Giffen, a twenty-five-year-old Protestant from County Antrim.

Given our contemporary understanding of gender and power dynamics, not to mention a long history of Irish sectarianism, O’Brien’s state of mind would be central to any consent argument in a court today.

It is one of the reasons that O’Brien v. Cunard S.S. Co. is a nineteenth century case that twenty-first century law students still study.

In addition, negligence (personal injury law) was a novel concept in 1889 when the benefit of the doubt automatically sided went to professionals or capitalists rather than to the poor. O’Brien should, from that perspective, have been grateful to Cunard rather than suing the company.

The historical record does not tell us about the extent to which Mary O’Brien’s encounter with Cunard and the Massachusetts legal system took a psychological toll, nor whether her skin condition cleared up with time.

She did not win a monetary settlement, nor ever get to tell her side of the story to a jury. The 1900 census records her working as a domestic servant for the family of a jewelry company executive who lived on Highland Avenue in Roxbury. Thereafter, the real woman fades from view even as the law cases in which her experience was central endure.

The following year brought a smallpox epidemic with a seventeen percent fatality rate to Boston. Once again, compulsory vaccination was seen as the only answer, despite the same resistance from anti-vaccinationists.

This epidemic led to a landmark 1905 U.S. Supreme Court case, Jacobson v. Massachusetts, which upheld the power of local boards of health to compel smallpox vaccination in the interest of the public good.

Curbing the spread of this dreaded disease was ultimately deemed more important than individual liberty.

One can only wonder if, in spite of everything, Mary O’Brien was then quite relieved that she had been vaccinated on the Catalonia.

Marion Casey is the founder and director of the Archives of Irish America at New York University.