I recall well a moving story that Maurice Brick, author and fluent Gaelic speaker, told me many years ago. He comes from the heart of the Ballyferriter Gaeltacht in West Kerry, and he was sent to a special hospital in Dublin to get treatment for a guttural problem when he was ten years old.

At the time, the only language he spoke was Irish. That was all he heard in his home and community. However, none of the nurses or ward staff understood a word he was saying.

In fact, they dealt with their unusual arrival from Kerry talking in a strange vernacular by giggling at his unusual speech. Being away from his family and unable to connect with those around him was a frightening situation for the youngster.

However, there was a nun on the staff who realized his predicament even though she too was not competent in Irish. But she came to his bed every night to read him a story in English. He remembers well the book she brought, "Robinson Crusoe" by Daniel Defoe. That eased his loneliness as he looked forward every day to her nocturnal bedside visits.

The Irish language is a mandated subject for every pupil in Ireland. This means that the school curriculum has to include one daily class period devoted to learning Gaelic. So, during eight years of primary education, all students would have in excess of a thousand hours focusing on the subject.

The workers in the hospital that cared for Mr. Brick should not have been bewildered by his speech. I don’t blame them, but it suggests a major pedagogical deficiency in teaching language skills.

Talk to Irish immigrants in New York and you are unlikely to hear a person who can string a sentence or two together in Gaelic, yet they all had abundant instruction time in the subject.

I taught Irish for a year to Intermediate certificate pupils, all around fifteen years old, in the College of Commerce in Rathmines in Dublin, this while I was completing the required teacher certification courses in University College Dublin.

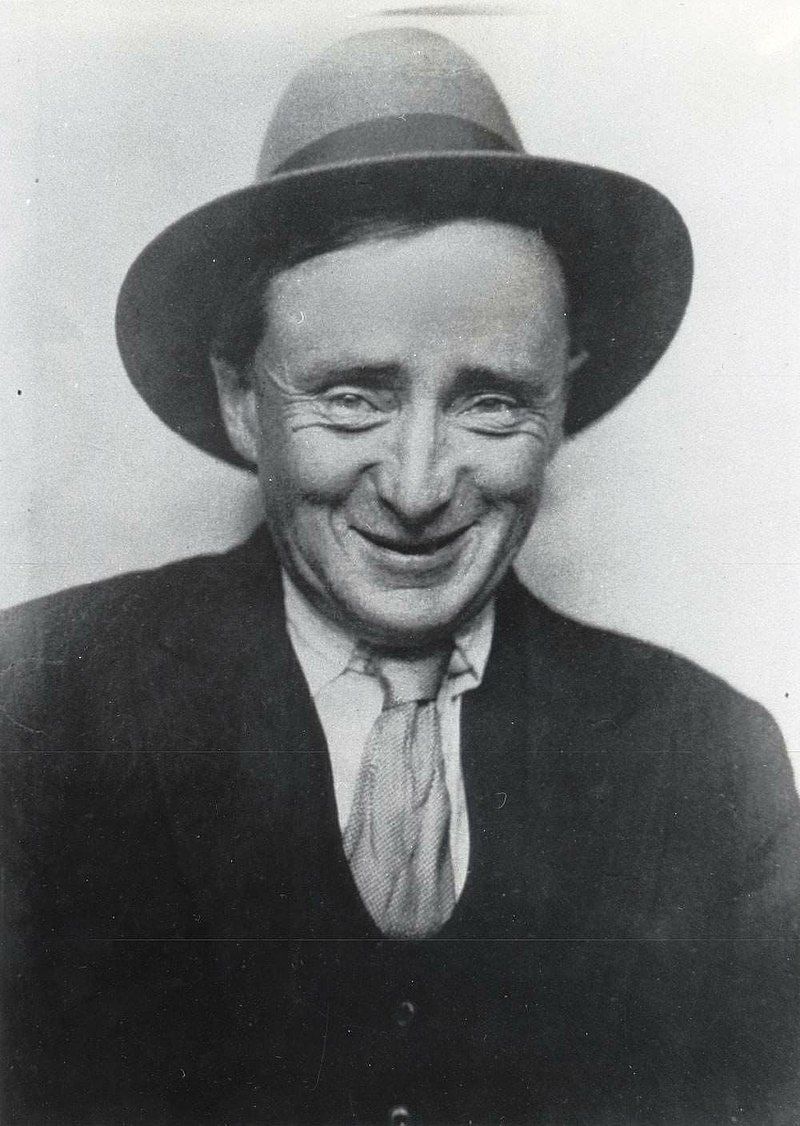

It was a negative experience. My class of about twenty-five students, all girls, were required to study a book titled Brian Og (Young Brian) by the distinguished Irish writer, Padraig O Conaire.

Padraig O Conaire.

The book told about a young man who left his home during the Penal Days in Ireland to study for the priesthood in Spain. This story did not resonate with my class who had difficulty reading simple sentences in Irish, never mind a 90-page book dealing with themes that did not stir their interest.

I wasn’t up to the task of motivating them, and I felt very inadequate standing before that class every day. I was painfully aware that my efforts were confirming their association of Irish with personal failure - a disaster that certainly left them with no love for their native tongue.

Except for two girls, their plight was summed up well in the words of the Australian writer, John O'Brien, in his ballad “Tangmalangaloo”: “Glum and dumb and undismayed through every bout they sat – they seemed to think that they were there but weren’t sure of that.”

My grandchildren living in Dublin are having a much better experience learning the language where the focus now seems to be on oral competence.

Colonial powers always try to undermine the local culture and replace it with their own. In 19th century Ireland, the English denigrated the literature, the games, the religion and the language of the local people. The inferiority complex, characteristic of so many Irish people, has its poisonous roots in colonialism.

The Irish language was associated with poverty. Ability to write and converse in English opened the door for emigrants going to Canada, England, Australia and the United States. My grandparents, from Lauragh in County Kerry, spoke Gaelic to each other, but they encouraged their ten children to learn English knowing that most of them would earn a living abroad.

Times and attitudes have changed for the better. Bilingualism, the ability to converse in two languages, common on the European mainland, is now viewed as a badge of distinction in many parts of Irish society. For example, there is far more Irish spoken in Dublin, especially among the middle-class, now than ever before.

On Monday March 21 an article in the New York Times covered the language revival movement in Belfast by focusing on the growth of Hip-Hop among young people there.

The rap group Kneecap is pioneering this new Irish language genre. The Times journalist, Una Mullaly, describes how the “band’s ramshackle rave and rudimentary hip-hop” mixing with republican politics, obliquely pushing for a united island, draws big crowds in Dublin and Belfast as well as a growing following in some English and Scottish cities.

Kneecap provides one unusual response to the chauvinism that Brexit represents from a nationalist community that voted overwhelmingly against breaking the tie with Europe. One of the band leaders suggests that they are part of an ongoing search for a new Irish identity, stripped of colonialism and Catholicism, delving into older Celtic spiritual and mythological roots.

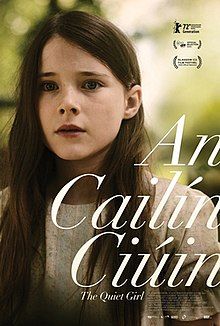

The latest Irish language film An Cailin Ciuin (The Quiet Girl) won two honors at the Berlin International Film Festival. More surprisingly, it beat out the Academy Award-nominated “Belfast” to win best film at the Irish Film and Television Awards. The movie’s narrative was adapted from a short story in the New Yorker magazine written by Claire Keegan.

Senator Niall Ó Donnghaile.

I had an interesting conversation about the growth of the Irish language in Northern Ireland at a recent conference with Senator Niall Ó Donnghaile from Belfast who represents Sinn Fein in the Senate in Dublin.

He points out that there has been a phenomenal growth in the use of Irish among teenagers and college students, not just from the nationalist community, who are comfortable speaking both languages. He claims that 10,000 young people in the North are proudly bilingual. This is a huge number in a small geographical area and represents a renaissance of the ancient language.

The association of the Irish language with poverty was a big obstacle facing revivalists. That day is gone. The Irish now – north and south – live in a relatively prosperous society, and, with a focus on Europe, they are increasingly in tune with modern thinking about the cool achievement of datheangachas, mastering two languages.

Gerry O'Shea blogs at wemustbetalking.com