I attended the annual commemoration of the untimely deaths in 1832 of 57 Irish laborers who worked and died at a stretch of railway track in Chester County, Pennsylvania known as Duffy’s Cut.

The service took place at Laurel Hill Cemetery located in the East Falls neighborhood of Philadelphia where a monument is erected in their memory.

The ceremony was conducted by Dr. William Watson, a History professor in nearby Immaculata University, and his twin brother, Frank, a Lutheran pastor in Whiting, New Jersey.

They were the driving force behind the research into the tragic happenings at Duffy’s Cut nearly two hundred years ago. After the vivacious Vincent Gallagher sang the anthems, the professor spoke, the priest prayed, and they were both part of the piping tribute.

Dr. William and a lady from the Donegal Society, author Marita Krivda, talked about the tragedy of the bodies of the young immigrants dumped in an improvised burial pit near the shanty where they lived. They extended their reflections to recognize the similar wailing cry emanating from the women and babies in the cratered Maternity Hospital in the Ukrainian city of Mariupol. Harrowing sadness and inhumanity joined, past and present.

On June 23rd 1832, the ship John Stamp docked at the port of Philadelphia, and a local Irish-born contractor, Philip Duffy, hired 57 of the passengers as laborers to complete a very cranky section of railroad, known as Track Mile 59 on the Pennsylvania-Columbia line.

They faced strong, nativist, anti-immigrant sentiments - still, unfortunately, prevalent in America today - which in those days identified Irish Catholic newcomers as a main source of the country’s problems. The bosses in the burgeoning coal and railroad companies used the penurious Irish as cheap labor while many local people viewed them as the source of the frightening cholera fever which was devastating their community.

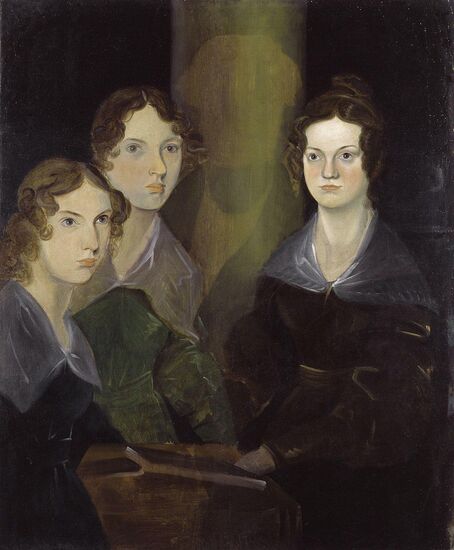

Clear evidence of violence. This skull with a bullet hole was dug up in 2010.

Philip Duffy took on many contracts with the local authorities, completing infrastructural work on roads and railroads, done at low cost. Duffy expected his laborers to live in their own shantytown and not mix with neighbors, who mostly viewed them as wild rowdies.

The workers came from three Ulster counties, Donegal, Derry and Tyrone. Later archaeological excavation in Duffy’s Cut showed the earliest artifact in America - a pipe with the clear inscription Erin go Bragh - revealing an awareness among the young immigrants of a sense of Irish nationhood. No doubt they were influenced by the United Irishmen rebellion in 1798, which started in Belfast and surrounding counties, asserting in arms the Irish right to a country, separate from England.

The widespread dislike of Catholics, especially those from Ireland, was due in part to the feeling that Rome had designs on taking over America and imposing its religion on the new country. This paranoia reached its apex in the 1850s with the growth of the ruthless and mean-spirited Know-Nothing Party.

The Irish immigrants in the 1830s felt the sting of prejudice. They were stereotyped as ignorant bogtrotters with strong allegiance to a foreign religion and so unsuited to the nascent American democracy. When the cholera epidemic spread to Philadelphia, predictably, the locals blamed the recently-arrived foreigners for the awful scourge.

Within six weeks of their arrival in late June 1832, all 57 workers were dead, allegedly from the fever that was raging in the community. Christy Moore and, more recently, the distinguished Tyrone singer and songwriter, Mickey Coleman, memorialized the Irish workers in an angry song about all the suffering and prejudice they endured.

"From Ballyshannon and The Glenties; They sailed right into hell; They suffered like the weeping Christ; Down Duffy’s Cut they sweat their blood Into his wishing well."

There is no record of Philip Duffy playing any positive part in trying to relieve the crisis the workers faced, and the song doesn’t spare him. The moving dirge includes lines about a noble blacksmith and Sisters of Charity who came from Philadelphia to provide succor for the poor misfortunes.

"The Blacksmith and the Holy Sisters; Good people through and through; Whispered prayers into the victims’ ears; It’s all that they could do; How come the bosses had silence on their lips; As 57 Irish Navvies were buried in a pit."

Many historians and medical experts doubt that all 57 workers in one place could have died from the fever. Research shows that there were 176 cases of cholera recorded in Philadelphia on the worst day of the 1832 infection, causing 71 deaths. Talking about 57 cases without even one survivor makes no sense.

The powerful railroad owners and developers did not want the full story told. It would have encumbered their plans as public sympathy would inevitably fixate on young workers perishing while their employers turned a blind eye to the devastation.

The plot thickens. Frank Watson, the current impressive pastor and piper, was bequeathed a trove of records by his grandfather, Joseph Tripician, who held an executive position in the railway company. He managed to hold on to the Duffy’s Cut file when the New York Central took over the Pennsylvania Railroad Company in 1968.

The information in these papers confirmed the suspicion that there were foul deeds committed at Duffy’s Cut. Fear and blind prejudice against the new immigrants led to dastardly acts which account for the plenitude of dead bodies.

In 2004, the Watson brothers brought together volunteer archaeologists to lead Immaculata students and members of the local Irish community in a major archaeological dig which, after a few years, yielded skulls, teeth and a wide variety of bones. Some of these skeletal remains provided definite proof of violent trauma caused by blunt force.

According to Dr. Watson, there is clear evidence that local vigilante groups, driven by intense hatred of the new Irish immigrants, and combined with a fear of the dreaded disease, were involved in the murders.

Five men and one woman whose remains were exhumed from the mass burial site were interred at the Laurel Hill cemetery in 2012 and they are remembered every year at a March commemoration. The skeletal remains of two others were buried in their home counties: Catherine Burns in Clonoe near Coalisland in County Tyrone, and the 18-year-old John Ruddy in Ardara in County Donegal.

The shantytown area still has an eerie feeling with sightings of ghosts continuing to the present day. Professor Watson told me a few years ago that he wouldn’t wander around it in the dark. He also said that the message heard from the dead here can be simply stated: they were real people with families who want respect for their persons and their life stories. They should not be dismissed as worthless nonentities thrown in a decaying pit.

Duffy’s Cut is a story for the ages. Young people at the bottom of the pecking order in their own country launching out with hope to find a new place offering opportunity and respect. It didn’t work out for the men and women who sailed from Ulster in 1832, young, hopeful, immigrants who only lasted a few weeks in the promised new world.

Gerry O'Shea blogs at wemustbetalking.com