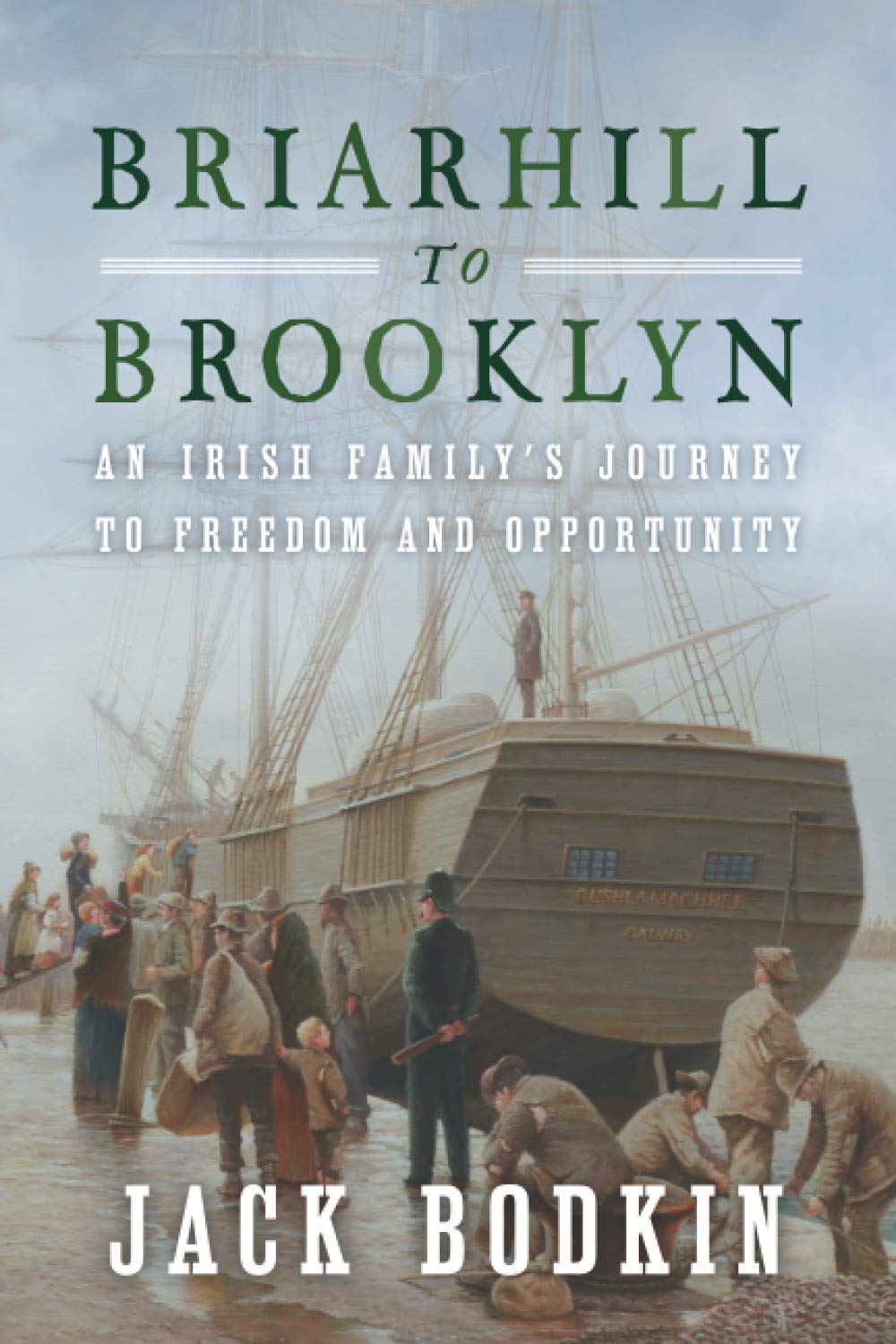

People often ask why I wrote my first novel, “Briarhill to Brooklyn: An Irish Family’s Journey to Freedom and Opportunity.”

The answer is pretty simple: I was afraid my Bodkin ancestors’ story would be lost.

I had worked on a family tree for several years and ultimately traced my Irish great-great-grandparents back to County Galway.

I even located the handwritten parish registers which detailed the baptismal records for some of their children in the 1820s and 1830s.

However, I found that no one else in my family was interested in my compilation of facts. I was not afraid that these bare facts: names and dates of birth and death, would be lost, but I was concerned that the struggles and the bravery my family shares with generations of Irishmen would be forgotten.

I decided I needed to tell their story in a way that would be more interesting than a family tree, more memorable. I wanted something my granddaughter would hand down to her granddaughter, decades from now.

I admit that ten years ago I didn’t know very many details about my family’s Irish lineage, but an Ancestry.com membership, combined with some research and a little luck, evolved into “Briarhill to Brooklyn.”

Jack Bodkin.

When doing presentations to American book clubs or library forums, I tell them I know Bodkin is not the most Irish-sounding name and, as a kid growing up on Long Island, I remember no one thought our family was Irish. But today, the Bodkin flag still flies proudly over Eyre Square in Galway City with the flags of the other thirteen families who comprise the ancient Tribes of Galway.

“Briarhill to Brooklyn,” published in 2021, is a work of creative nonfiction in which I tell the story of my Irish Catholic family’s journey from County Galway on a coffin ship named Cushlamachree. The family, John and Eleanor Bodkin, and seven of their children, began their journey on St. Patrick’s Day, 1848. Their destination was Brooklyn.

The main characters in my book are real people - my ancestors - and the locations, events and timelines are generally historically accurate. Some of the book is fact, but much of the story is fiction. The tale I relates what I have imagined about my Irish ancestors’ lives between 1848 and 1902. It is fiction sewn together with places, names and dates I have found in my research.

The prologue sets the stage for the immigrants’ story, using the retrospective voice of a first-person narrator. The narrator, who is actually my great-grandfather as a young boy, describes the family crowding around the table in their Briarhill cottage for a meal of potatoes boiled with a turnip and butter from a neighbor’s cow.

The young storyteller recalls his mam talking to his da. “John, do todhchaí ár bpáistí, ní mór dúinn dul go Meiriceá,” me mam said, looking straight into Da’s eyes. Her words, etched into me brain forever, startled me. “John, for the future of our children, we must go to America.”

The British parliament’s role in the starvation of the Irish people is clear from the opening pages of “Briarhill to Brooklyn,” and you will understand the tragic conditions in famine-era Galway City as the narrator relates the startling images he encountered walking down William Street in the ancient city.

“The front of the soup line was at old Lynch’s Castle on Upper Abbeygate Street, where three elderly nuns - Sisters of Mercy, Da said - ladled soup from a steaming cauldron into tin cups. A fat British overseer barked at one of the sisters, “Remember, papist! Only one cup per person! Someone should have driven a stake through the son-of-a-bitch’s heart - to this day I wish I had.”

The early chapters establish the novel’s several storylines, and the first half of the book is consumed by the family’s final few days in Ireland, their steerage voyage across the Atlantic and the Cushlamachree’s landing in Lower Manhattan.

An unimaginable hurdle confronts the family after they arrive in Brooklyn, but the siblings survive and manage to assimilate into New York’s burgeoning and contentious melting pot.

Clearly, the most significant event that transpired in the United States after the Bodkins docked at South Street in 1848 was the Civil War, and several chapters of “Briarhill to Brooklyn” detail the impact the war had on the seven siblings.

Two of the Bodkin brothers enlisted in the Union Army as the war raged, and while the younger brother bides two years of his time guarding the peaceful and bucolic city of New Orleans, the older of the two brothers becomes a fledgling surgeon on battlefields outside Mobile, Alabama.

The chapter titled “Battles” chronicles the scene in a Union medical tent supporting the Battle of Spanish Fort on April 8, 1865 - only one day before the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House.

An unimaginable hurdle confronts the family after they arrive in Brooklyn, but the siblings survive and manage to assimilate into New York’s burgeoning and contentious melting pot.

“The catastrophic nature and the sheer volume of the injuries were nothing the physicians from New York and Philadelphia had ever dealt with before. Seventy percent of the soldiers’ wounds were to their extremities - arms and legs blown apart by cannonballs, or soft lead bullets called ‘Minié balls.’ The surgeons’ first goal was to save a life - next was to keep a limb. Often they did not achieve either.”

In a seemingly unbelievable aspect of the family’s history, “Briarhill to Brooklyn” focuses on the oldest son Dominic’s transformation from penniless but resourceful orphan to medical student at the University of the City of New York. The line between fact and fiction is always blurred in my work of creative nonfiction, but the narrative, as it relates to my great-great-uncle, Dominic George Bodkin, MD, is well documented: an Irish immigrant house painter who became one of the most respected and preeminent physicians in Brooklyn at the turn of the twentieth century.

The tale I tell in “Briarhill to Brooklyn” is not quite rags to riches, but it is an Irish family’s success story. The journey I describe - fleeing Ireland, the voyage in steerage, a new life in Brooklyn, the Civil War, prosperity - has caused many American Irish immigrants to think, “This could be my family.”

Galway historian, author and archaeologist, Peadar O’Dowd, wrote in the Galway City Tribune about Briarhill to Brooklyn, “It’s an amazing work, which tells how the surviving seven siblings, after arriving in New York on one of the infamous coffin ships, eventually merged into the American way of life, so different from the simple farm existence they left, east of Briarhill on the now distant Green Isle.”

Jack Bodkin was born in Brooklyn, grew up in Merrick on Long Island, and graduated from Chaminade High School. An alumnus of Wheeling College in West Virginia, Bodkin is a retired certified public accountant who began his career working in the New York City office of an international public accounting firm. In 1977 he returned to West Virginia, where he still resides. “Briarhill to Brooklyn” is available on Amazon.