Without a huge system of aqueducts to provide water, Los Angeles never could have grown into California’s largest city and Angelinos can thank Irishman William Mulholland for that. Though he is honored by the city’s famed Mulholland Drive, few people today recall Mulholland’s story or his amazing achievements.

Born in Belfast in 1855, Mulholland’s parents, Hugh and Ellen Mulholland, were Dubliners who soon returned with him to their city shortly after William's birth. In 1862, when William was seven years old, his mother died and three years later his father remarried. Educated by the Christian Brothers at O’Connell School, in Dublin, Mulholland received poor grades, for which his father gave him a beating. Resolving not only to leave school, but also Ireland, Mulholland joined the British Merchant Marine at age 15 where he spent his next four years as a seaman, making 19 Atlantic crossings.

Fascinated by tales of America, Mulholland jumped ship in New York in 1874 and headed west. He worked for a while on a Great Lakes freighter and then as a lumber jack. Later, he almost lost a leg while felling a tree and decided to move to Ohio where he reconnected with his brother, Hugh. Two years later, the brothers stowed away on a ship headed to California via the southern tip of South America. The stowaways were discovered and had to leave the vessel in Panama. To save the $25 in gold fare to cross the isthmus, the brothers instead chose to walk the 47 miles from Colon to Balboa and then worked their way to California as crew members on a ship bound for San Francisco, sailing through the Golden Gate in February 1877.

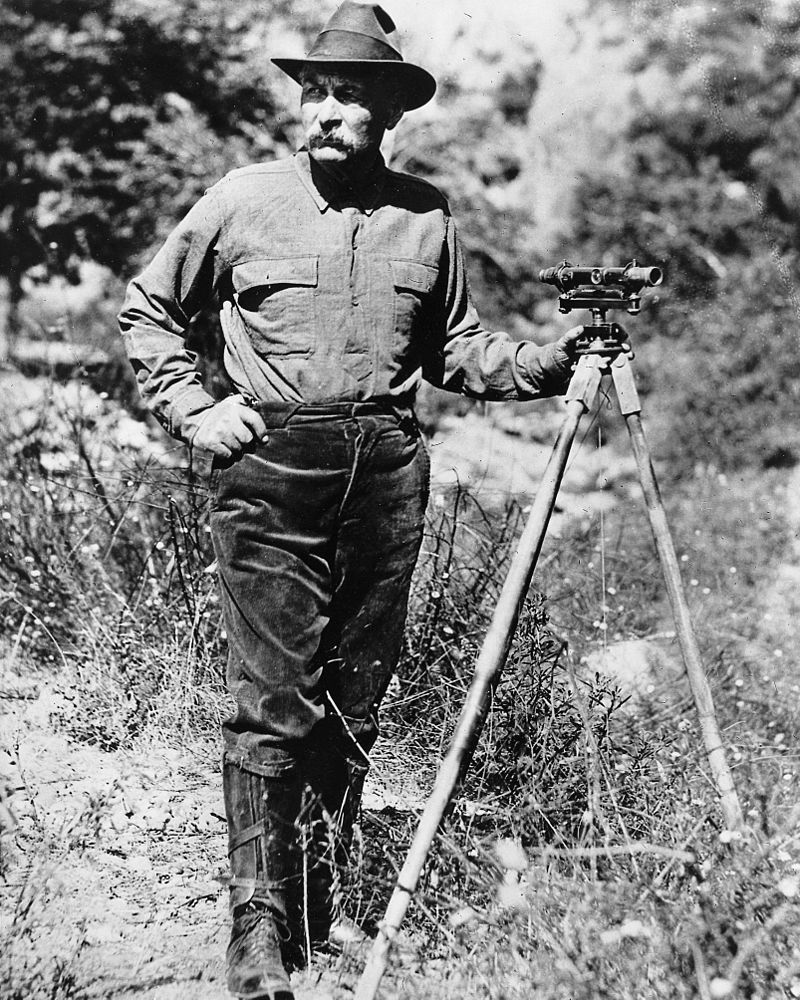

Mulholland made his way to the then tiny town of Los Angeles, which had a population of only 9,000 people. Getting a job as a humble zanjero, or person who tended to the town’s irrigation ditches, he would devote 50 years of his life to allowing the city to develop its water infrastructure. Mulholland's first job was only to maintain this rudimentary water system, but after doing his day's work, the Irishman determined to master the study of water systems, absorbing textbooks on mathematics, hydraulics and geology on his own. Through strength of character and knowledge, he advanced from ditch tender to straw boss, to foreman, to superintendent. In 1880, Mulholland supervised the laying of the first iron water pipeline in Los Angeles, which dramatically reduced evaporation of water. Though he left for a short time to work on other water projects in California, he returned to Los Angeles and worked as the town’s water superintendent until 1902 when the city’s water commission was liquidated, and was named as the Los Angeles Water Department’s first ever superintendent.

A visionary, Mulholland foresaw Los Angeles massive growth, but realized that the area’s semi-arid climate and limited water supply necessitated developing a system of aqueducts. Mulholland famously once said, "If you don't get the water, you won't need it." He initiated a public works program to irrigate large areas of previously arid land, spurring rapid population growth. Mulholland understood that the area’s appetite for water could only be quenched by gaining control of the Owens Valley, a lush area watered by runoff from the Sierra Nevada Mountains. From 1902 to 1905, Mulholland and others tricked the valley’s residents into not developing their own water infrastructure system by representing themselves as working on a public irrigation project for the Owens Valley, but in actuality Mulholland and others were buying the land and water rights for Los Angeles, which he purchased for a pittance.

The irate residents of the Owens Valley fought back with a vengeance, starting what were called the California Water Wars. At the height of the conflict, parts of the aqueduct system were sabotaged and even dynamited. In 1974, Roman Polanski’s film noir classic “Chinatown” dramatized a highly fictionalized version of the conflict presenting Mulholland as the character Hollis Mulwray.

His crowning achievement was the completion of the great aqueduct that stretches 233 miles from the Owens River to Los Angeles, serving millions with water fed by the snows of the distant Eastern Sierras. Mulholland, directing an army of 5,000 men who labored for five years, completed on time and under budget what was then the most difficult American water engineering project ever undertaken. When The first aqueduct water reached Los Angeles on November 5, 1913, the city celebrated with an extravagant civic ceremony at the aqueduct’s terminus in the San Fernando Valley. Speaking there, Mulholland said with characteristic brevity and modesty: "There it is: take it." The city was now poised to develop into a great metropolis and The Los Angeles Aqueduct remains to this day one of the modern world’s greatest engineering triumphs.

Mulholland was also the first American engineer to utilize hydraulic sluicing to build a dam at the Silver Lake Reservoir in 1906. This radically new construction idea attracted nationwide attention and government engineers adopted his method in building Gatun Dam in the Panama Canal Zone.

However, his construction of one of the dams in the Los Angeles aqueduct system would haunt him to the end of his days and lead to his demise. On March 12, 1928, only a few hours after an inspection and assurances of safety by Mulholland, the St. Francis Dam, one of several dams he had built to increase storage of Owens River water, collapsed, sending 12 billion gallons of water gushing into the Santa Clara Valley, and claiming more than 400 lives. Though Mulholland was cleared of any charges, since the instability of the rock formations could never have been detected by geologists of the 1920s, his career and reputation lay ruined. Mulholland, who was plagued by guilt from the collapse until the end of his days in 1935, said “If there is an error of human judgment, I am the human.”

On Aug. 1, 1940, a memorial fountain was dedicated to him, just steps from the shack where he had begun as a zanjero. A five-ton pink granite boulder, whose beauty Mulholland once commented on while building the city’s aqueduct, stands at the memorial approach. A memorial plaque on the boulder reads: “To William Mulholland (1855-1935): A Penniless Irish Immigrant Boy who Rose by the Force of his Industry, Intelligence, Integrity, and Intrepidity to be a Sturdy American Citizen, a Self-Educated Engineering Genius, a Whole-Hearted Humanitarian, the Father of this City’s Water System, and the Builder of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. This Memorial is Gratefully Dedicated to those who are the Recipients of His Unselfish Bounty and the Beneficiaries of His Prophetic Vision.”