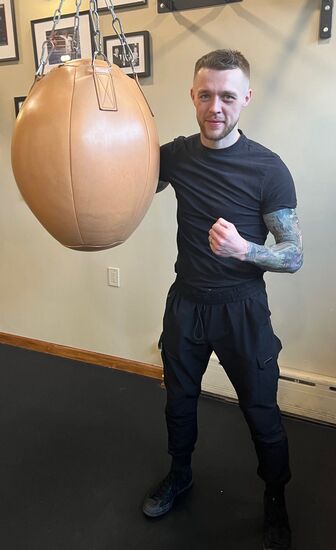

The author, right, with the late Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin.

By Mel Mercier

I met Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin for the first time in the mid-1970s, at the RTÉ studios in Dublin where he was recording music for the groundbreaking traditional music radio programme “The Long Note.” Tony MacMahon, the well-known accordion player and producer of “The Long Note,” had invited me and my older brother Paul to add the pulse of the bodhrán and the rattle of bones to Mícheál’s boldly inventive musical arrangements of short, musical links for the programme. I can still remember the excitement I felt walking into the studio that day. Mícheál had a bright energy about him. A charisma. I was 15, he was about 24, and that first encounter marks the beginning of a defining relationship in my life.

Paul and I had taken the bus to the RTÉ studios that day with my father, Peadar Mercier, himself a bodhrán and bones player. He came along to meet Tony, with whom he had performed often, and Mícheál, whom he didn’t know, but whom I suspect he was curious to meet. Mícheál and my father shared a fascination with the bodhrán, at a time when the instrument was still relatively unknown. When my father taught himself to play the bodhrán in the mid-1950s, it was primarily associated with the annual St. Stephen’s Day tradition of hunting the wren and still considered to be a ritual instrument rather than a musical one. He made his first drum using the old methods, soaking a goatskin in the bath at home for a week before stretching it over the rim of a garden sieve. He also fashioned a pair of rhythm bones from cow ribs he picked up at the local butcher shop. My father played the bodhrán in the North Kerry style, striking the skin with a double-ended, knobbed beater to produce rolling reel and jig rhythms.

Mícheál first heard the bodhrán in the mid-1960s when he attended a production of John B. Keane’s play, “Sive,” in his hometown of Clonmel. Keane exploited the shamanic resonances of the instrument, placing it in the hands of his character, Carthalawn, the traveling tinker-seer who beat the drumskin to underscore his portentous verse. A few years later, in 1972, in his final year of a music degree at University College Cork, Mícheál, with guidance from Keane, carried out some of the earliest research into the bodhrán and wrote a minor dissertation about the instrument, which he based on interviews with older bodhrán makers and bodhrán players in North Kerry, South Tipperary, Clare and West Limerick.

Mícheál and my father also shared a significant connection with another exponent and advocate of the bodhrán, the iconic composer and performer Seán Ó Riada. In the early 1960s, Ó Riada elevated the bodhrán to the status of a musical instrument by bringing it, in his own hands, onto the concert stage as part of his pioneering Irish traditional music ensemble, Ceoltóirí Cualann. Some few years later, when he began to lead the ensemble from the harpsichord, Ó Riada invited my father to take over as the bodhrán player in the group. Mícheál, meanwhile, had come under Ó Riada’s influence while studying music at University College Cork, where the well-known composer of the score for the film Mise Éire was a lecturer. He shared Ó Riada’s passion for Irish traditional music and classical music, and he inherited his extraordinary gift for interpreting Irish music on the harpsichord and piano. Mícheál would go on to pay tribute to Ó Riada in words and music throughout his life.

By the time we took that short bus journey to RTÉ to meet Mícheál in 1974, Seán Ó Riada had died and Ceoltóirí Cualann was no more. Mícheál’s book “The Bodhrán,” the first publication dedicated to the instrument, was soon to be issued. My father was performing with the Chieftains as the first professional bodhrán and bones player, and my brother and I had been inspired to take up the instruments ourselves some years earlier. Entrained to my father’s groove and tuned into his sound world, we had been lifted by the gathering wave of the Irish traditional music revival in the late 1960s. Now, in the early years of the 1970s, caught up in our own swell of familial pride, we watched our dad surf that wave as it broke on international shores.

In the decades that followed, Mícheál played a central role in the shaping of Irish music and I was blessed often by his invitations to travel with him on his visionary journeys in music and education. In 1975, he recorded his debut album on the Gael Linn label, a collection of solo interpretations of traditional music on piano, clavichord, harmonium and Moog synthesiser. He went on to record over 12 more albums, which include compositions and arrangements for traditional flute and string orchestra, piano and chamber orchestra, choir and orchestra, a hiberno-jazz ensemble, sean-nós singers and symphony orchestra, set-dancers and sean-nós dancers. He appeared on concert stages throughout the world, from Delhi to Dublin, and the Albert Hall to Hosford’s Garden Centre in Clonakilty. A popular media personality, his many television credits include the groundbreaking series, “A River of Sound,” which he devised and presented.

Mícheál’s career as an innovative and visionary educator began with his appointment as a lecturer in music at University College Cork in 1975. It was during his time there, in the Department of Music, that he pioneered an approach to music education that located music making itself – music and musicians – at its core. He advocated for a parity of esteem for Irish traditional music alongside classical music and he successfully led the integration of Irish traditonal music into the university curriculum, creating access for the first generation of young Irish singers, fiddlers, uileann pipers, harpers, concertina, whistle, accordion, and bodhrán players to a university education in the traditional arts. In 1994, he was appointed as the Founding Chair and Professor of Music at the University of Limerick where he established the internationally renowned Irish World Academy of Music and Dance.

A champion of the profound significance of cultural work, Mícheál believed in the positive, transformational potential of artistic expression. For 50 years he tapped into a deep well of creativity, its energy flowing irrepressibly through him, moving him effortlessly between the past, present and future, the local and the global. In the fluid, liminal space between worlds he was at his most powerful. Throughout his life, whenever he wrote or spoke about Irish music and song, Mícheál brought their rich histories to life. By illuminating their meaning and their importance he made an invaluable and lasting contribution to the national and international cultural conversation.

Mícheál died on Nov. 7, 2018. Admired and beloved of his students, colleagues, fellow musicians, friends and audiences alike, his ultimate vision was both humanitarian and spiritual in the widest sense. That vision is given voice in his own music and the musical legacy he has bequeathed to so many. I cannot begin to fathom the loss for his family of this remarkable man, and it is too soon, or maybe just too great a task for me, to understand or appreciate the depth of his contributions to Irish cultural life, or the immensity of his gifts to me as a mentor, fellow-musician, colleague and friend. What I cherish most of all are those many sublime moments when I sat with my bodhrán and bones in the well of the piano, swept up and transported by the force of Mícheál’s ebullient energy, searching out the deepest grooves in his fluid, inventive and richly textured synthesis of traditional, classical and jazz musics. What I miss most of all is the familiar, magical, ritual space of our duet, with its potent mix of pulse, play, discovery, humor, tenderness and possibility.

Mel Mercier is Professor and Chair of Performing Arts at the Irish World Academy of Music and Dance, University of Limerick.