An Irish priest discovered recently that over 40 years ago he’d become a likely target for assassination.

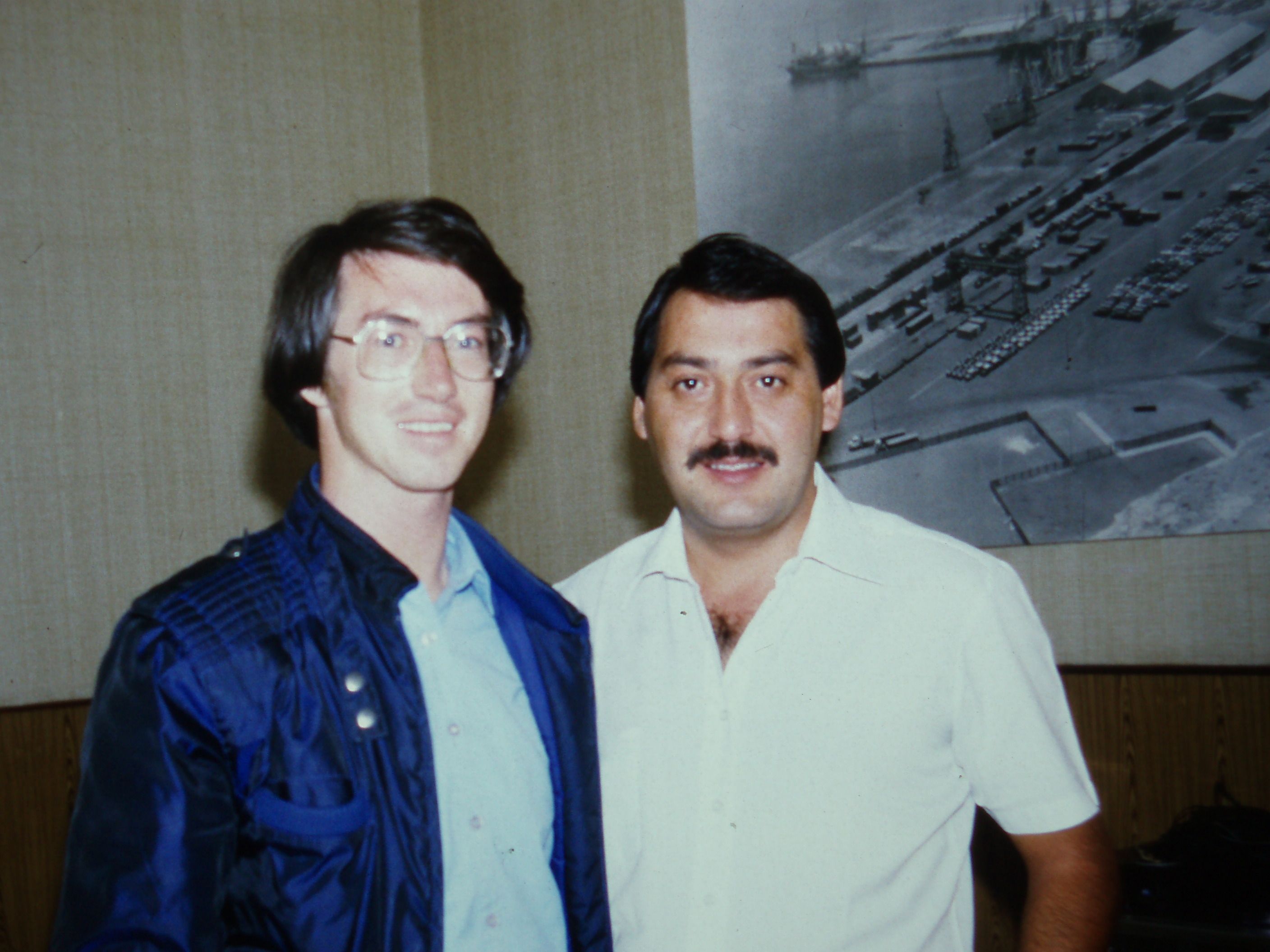

Inspired by liberation theology and also the non-violent philosophy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Rev. Michael O’Sullivan was active in organizing people in the small city of Arica in northern Chile near the border with Peru.

General Augusto Pinochet’s regime was a well-known example of a right-wing dictatorship, having overthrown democratic institutions in Chile a decade earlier, on Sept. 11, 1973.

Despite the rhetoric we’ve heard in the last couple of weeks in the wake of the murder of Charlie Kirk in Utah, the opposite has never happened: that is, the left has never overthrown a democracy in a Western country — indeed it hasn’t even come close or even tried. There are no Jan. 6ths in its closet.

Still, Rep. Bob Onder of Missouri felt he could say in the aftermath of the Sept. 10, 2025, assassination: “Everything has changed. If we didn't know it already, there is no longer any middle ground. Some of the American left are undoubtedly well-meaning people, but their ideology is pure evil.”

The congressman continued, “They hate the good, the truth, and the beautiful and embrace the evil, the false, and the ugly. And they literally will kill those with whom they disagree, just as their predecessor[s], leftist Marx and Stalin and Lenin and Pol Pot and Fidel Castro did.”

O’Sullivan, however, was part of a tradition that believes in constitutional democracy, call it leftist if you wish, or left of center, that aimed for people to recover their rights and their human dignity lost under Pinochet.

The 31-year-old knew he was taking a risk leaving Ireland for Latin America in 1982. Luis Epinal, a Spanish Jesuit considered an inspiration by young members of the order in Ireland, was kidnapped, tortured and killed in Bolivia by a pro-government death squad on March 21, 1980. Pope Francis visited the site of his murder in 2015 saying the Jesuit, "preached the Gospel, the Gospel that bothered them, and because of this they got rid of him.” (The future pope was studying English in Dublin at the time.)

Three days after Epinal’s death, human rights advocate Archbishop Óscar Romero of El Salvador was assassinated saying Mass. The funeral for Romero, who was canonized in 2018, attracted 250,000 people from around the world; journalists estimated that between 30 and 50 of the mourners were killed by bombs and gunfire. On Dec. 2 of the same year, four American churchwomen, three of them members of religious orders, were raped and murdered by members of the Salvadoran military. “So, it was a time of terrible slaughter of Christians who were standing up to politically repressive regimes,” the Limerick City-born priest recalled.

O’Sullivan found that the people of Arica had been traumatized by the coup, in which 3,000 had been killed or permanently disappeared in its immediate aftermath. Additionally, more than 30,000 had been arrested, and most of them had been tortured or ill-treated in some manner, it’s now recognized. And 200,000 people went into exile from a country with a population about the same at the time as New York City.

The priest became the subject of a campaign of intimidation — two of the three wooden churches he was pastor for were targeted in arson attacks. Then late one night, when he was walking home from a meeting, someone in a car tried to run him down. Subsequent to that incident, he heard second or third hand about verbal threats made against him. He improved his personal security. For instance, following parishioners’ advice, he didn’t travel after 9 at night. Generally, though, he took the threats in his stride, seeing them as part of the price of standing up for people and encouraging them to stand up for themselves.

Arica became an important center of pro-democracy and anti-regime activity (in the top five of “most combative” places, according to a Catholic agency) as O’Sullivan worked alongside a human-rights lawyer, a medical doctor and others who’d stepped forward into leadership roles.

With a downturn in the economy, labor and the banned political parties began to become more active nationally. In 1983, under the leadership of Rodolfo Seguel, the Christian trade union leader, and partly inspired by the Polish Solidarity movement, a one-day national day of action was called. The police cracked down, killing several demonstrators, but the movement wasn’t deterred and opposition became more widespread.

In 1984, O’Sullivan’s superiors in the Jesuits in Chile told him he should leave the country. He said that the regime’s agents may not attack him, but they might instead target someone close to him and also attempt to undermine the Jesuits’ projects throughout the country.

He had taken a vow of obedience when he joined the Society of Jesus, as the priestly order is called formally. Thus, to stay a Jesuit, he would have to obey. He wasn’t happy about it. “I felt I was abandoning people,” he remembered.

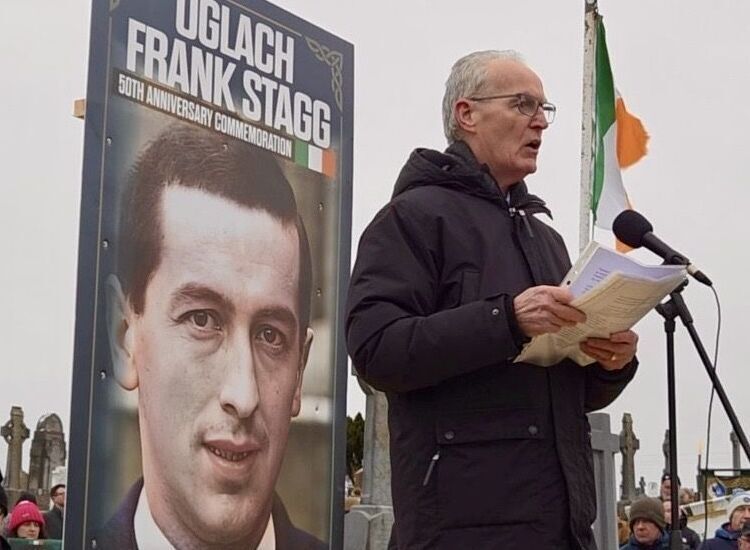

O’Sullivan, founder in Dublin of the Spirituality Institute for Research and Education and senior lecturer emeritus of the South East Technological University in Waterford, had made very occasional trips back to Arica after the fall of the dictatorship in 1989, but a visit in 2025 was in part to take up invitations from two years ago to mark the 50th anniversary of the military coup, including one to speak at the human rights museum in the capital, Santiago.

He heard during his four-week stay that friends and others in piecing together the story of his removal, which was abrupt, learned that the Jesuits had information in 1984 that O’Sullivan would be killed.

So instead of his martyrdom being a possibility, as he’d thought, it may have been a probability. The Jesuits had saved him.

The Pinochet regime, of course, had a long-time policy of killing prominent opponents, not least in foreign lands. Among them was the constitutionalist General Carlos Prats and his wife Sofia, who were assassinated in a car bomb in Buenos Aires in 1974. On Sept. 21, 1976, a car bomb killed the former Chilean ambassador to the U.S. Orlando Letelier and Ronni Karpen Moffitt, the wife of his secretary and translator Michael Moffitt, who was badly injured. The attack took place on Embassy Row in Washington D.C., where the regime had many friends and allies, and still has admirers.

By this point in history, one could say the Catholic Church was embarrassed at its past support for General Francisco Franco, who after his victory in the Spanish Civil War unleashed a “white terror,” which included the wholesale execution of captured combatants. Professional historians have offered different estimates of the number of victims, but they’re generally well into the six figures. Salazar, in Portugal next door, was not so bloodthirsty, but there, the long dictatorship kept the people uneducated and poor, and it eventually unraveled as a result of its colonial wars in Africa that were costly in terms of lives and finance.

The pattern would be become familiar, but was patented by Mussolini in 1922 — the respectable conservatives in the military, in the police and in the state apparatus together with right-wing commentators and business interests, shrugged their shoulders and said, “Well, why not?” Let those causing the most mayhem take over for a while; they were preferable to those others committed to democratic change and pluralism.

V.I. Lenin, the demon child of the Western left, was responsible for the totalitarian alternative, beginning with his Bolshevik Revolution, which swept over a militarily and spiritually broken Russia towards the end of World War I.

His successor Stalin could after World War II impose Soviet-style rule on countries occupied by the Red Army.

Military victory over an already existing tyranny brought Castro to power in Cuba, and Marxism-Leninism was the official ideology of various guerrilla wars that led to victories over colonial rule in Asia and Africa.

In Western countries by way of contrast, labor, the left and progressives generally have been associated with the expansion of freedom, not its opposite, and the fight against tyranny.

It should be remembered, for example, that Winston Churchill depended upon the Labour Party members of the War Cabinet to be installed as prime minister in 1940; leader of the Free French, General Charles de Gaulle, whose politics would turn out to be center-right domestically, praised the socialists and left for backing him in his lonely stand when disproportionately conservatives supported the collaborationist Vichy regime from 1940.

Here’s something else for Missouri’s Congressman Onder to ponder. It’s often said that democracies don’t make war on other democracies. There is, apparently, a lot of the data to support the idea, “democratic peace theory,” that can be traced back to the great journalistic advocate for the American Revolution Thomas Paine and the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. By the same token, one part of a democracy, if it is truly democratic, should not make “war” on another part, one that is innocent of the charges made.

For the podcast episode entitled "Returning to Chile," click here.