Way back in 1963 I had returned to St. Patrick’s Seminary in Carlow from my Christmas vacation at my home in Ballina, Co. Mayo. The craic was good and the holiday was happy, sort of.

Dances and female-company mixers were out. It was card-playing for us clerical students, in turns, in our own homes. Our parents supplied the drinks--lemonade, orange, tea--and cakes as we watched our pennies go out the door after poker and games of Twenty-Five.

When the New Year came, it was time to hug my mom and dad goodbye, as well as our terrier pup, and head off back to Carlow. The family chorus rang in my ears: “It won't be long now,” meaning my ordination, a secure permanent job, and a place in heaven for all my family. But that was still three years away--and I was only 21 years old.

Back in Carlow, my roommate, Tom Phelan, and I recounted our Christmas adventure. Then we wandered around to see if our classmates were back and intact or if some of them were missing and had taken other options than the road we had chosen.

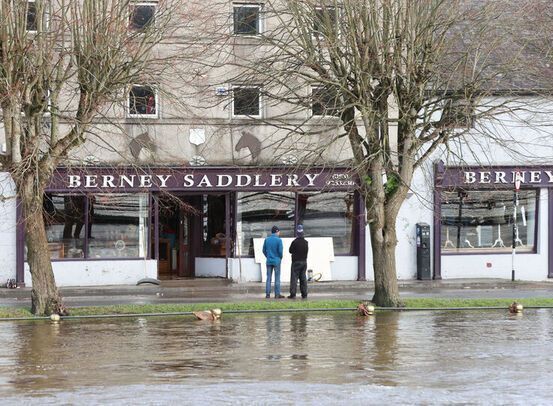

As January rolled on, the weather was wintry and not sociable for walking or playing Gaelic games. Where could we dry heavy, wet football boots and socks? Nowhere.

The pool table and tennis table each allowed for four people max in a school of 150 students. Boring times being stuck inside. We had enough of H. Noldin and company and dull textbooks on theology.

After supper on a dark and wet mid-January evening, Tom and I were in our room discussing why we were in the seminary and where we were going. We looked out from our desks over the bleak and bare college grounds. It seemed we were to be ordained to enforce the law—“Thou shalt not…”--and as Tom said, “To lead the hungry flock who are waiting to be fed with balm and comfort, only to say obey and do more penance.” This from a church whose members gave a Sunday donation. For what?

Tom's priestly future was to be in the south of England, and I was bound for New York. We had no notion of what our work environments would look like. We were still idealistic. And clueless.

We were destined to join a clerical society where the Council of Trent still ruled, and we would be the stormtroopers arriving to change centuries-old traditions. It would be a suicide mission, and we were not equipped for it. Vatican II was under way but nobody told that to the pastors to whom we would be assigned. That was the rub: the new and old would collide.

Titian painted this portrait of Pope Paul III in 1543, two years before the pontiff initiated the Council of Trent. [National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples]

Tom and I began to speculate about what we could achieve together in Australia, as the Australian government had a scheme for Irish people to migrate, with the passage to be paid back later. Becoming sheep barons, cattle ranchers, or outback tour guides were our dream fodder. We could deal with roos, wallabies, dingoes, and all outback critters. After all, Tom was a bona fide Laois farmer, and I was an experienced Mayo townie.

In a lecture about the need to be vigilant of worldly temptations, our spiritual director mentioned a newly ordained past pupil who, on a six-week voyage to Australia, succumbed to the pleasures of the flesh and landed off the boat with a wife in tow. This was the quality of spiritual direction we were accustomed to: “Beware of temptation and do not stray off the rails.‘’

That January we were both in a deep state of uncertainty about the road we were on. In fact, we were ready to quit. I recalled my father’s words to me when I was home for Christmas: “Remember you can always come home.” He must have sensed something was wrong, and his words reassured me that it was my decision to stay or leave. Still, we were immature teenagers at heart. We were men in our twenties, having no independence, no girlfriends, no money. We were even dependent on our parents to keep us in cigarettes.

Tom and I planned to work in England that summer and earn the money to bankroll our stay in Australia. Then we could mosey about and see what was out there for us.

Soon the weather improved, our spirits lifted, and we and our fellow seminarians received tonsure (a bad haircut from the local bishop), making us official clerics. It was the first step in being anointed priests and sent on our way to parishes or foreign missions. But at the time, we would have been more suited for the foreign legion.

We channeled our creative and restless energy into the college yearbook, college plays, pushing college rules and protocol, and practicing any devilment short of a reason for being expelled. Instead of heading to Australia, though, we made other plans for that summer, working first in England and then doing the Grand Tour. Our parents thought that a better alternative.

In London, we worked the night shift in a bacon factory. We sat on stools with trays of sliced bacon on our left and a scale on our right, packed the meat into cellophane bags, and slapped the label on. The other workers were mostly feuding Greek and Turkish Cypriots, which led to nighttime knifings and physical altercations. We lived through that, got our money, and headed for Europe, where we made the Grand Tour in a yellow Vauxhall.

And that was the end of our Aussie reverie of what might have been. We kept the faith, got ordained, and soldiered on, to the relief of our parents. Giving our all for eleven years for the parishioners we served, some who remained lifelong friends before and after we finally succumbed to Sanity and Temptation.

Who knows, we could have been the first Crocodile Phelan and Kangaroo Clarke in Aussie lore. Beating the Crocodile Dundee yarn by twenty years.

Seamus Clarke lives in Land O’ Lakes, Fla.