“This Side of Paradise’ unfurled like a banner over an entire age."

So wrote A. Scott Berg in his biography “Max Perkins: Editor of Genius.”

Its most famous reviewer, H.L. Mencken, wrote that the 23-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald had produced “a truly amazing first novel— original in structure, extremely sophisticated in manner, and adorned with a brilliancy that is as rare in American writing as honesty is in American statecraft.”

Perkins was the only reader at the New York publishing house Charles Scribner’s Sons who liked an earlier version that the young Minnesotan had written as a 21-year-old U.S. Army lieutenant at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He encouraged him to work on a new manuscript, which he did in his parents home at 599 Summit Ave., St. Paul, through the summer of 1919.

Perkins, whose later world-famous finds included Ernest Hemingway and Thomas Wolfe, only got it accepted finally by threatening to quit. He said that Fitzgerald would be published elsewhere and other young authors would follow him. “Then we might as well go out of business,” he told his conservative bosses, who thought “This Side of Paradise” frivolous and without literary value.

But Fitzgerald had another important champion in Shane Leslie, an aristocrat from County Monaghan, first cousin to Winston Churchill, Catholic convert, nationalist parliamentary candidate, author, journalist and lecturer, who’d first became acquainted with the future novelist when he gave a talk at his school

Expecting to be shipped out to Europe in early 1918, the young soldier entrusted for safekeeping the early attempt, which he called “The Romantic Egotist,” to Leslie, who then sent it to his New York publisher, Scribner’s.

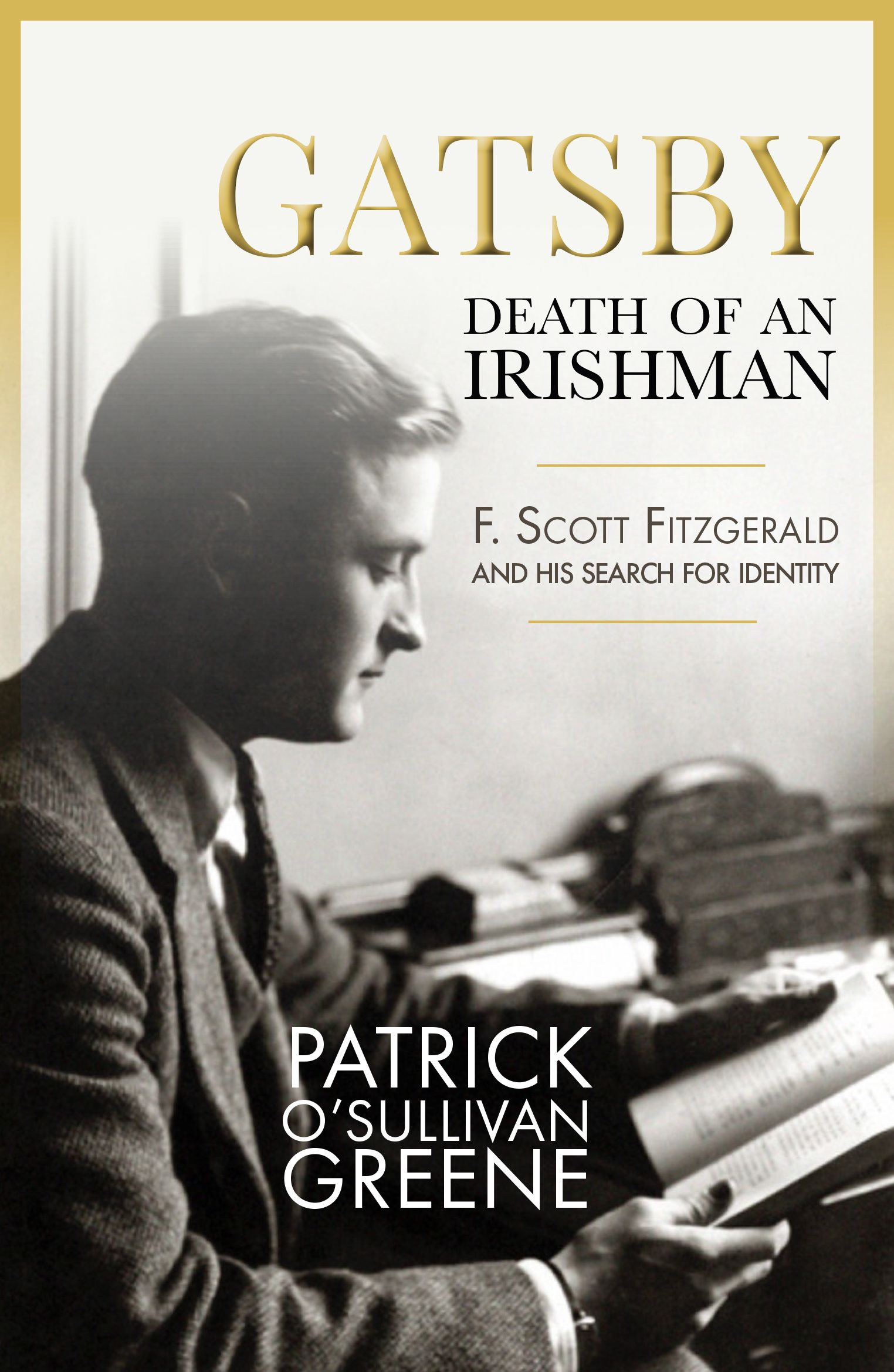

In his new work, “Gatsby: Death of an Irishman,” Patrick O’Sullivan Greene writes that Fitzgerald called Sir John Leslie, 3rd Baronet, the “most romantic figure I had ever known.”

The Eton- and Cambridge-educated Leslie, who adopted the more Irish-sounding Shane as his first name, renounced his right of succession to a vast family estate, though he retained his title.

“Leslie captivated Scott with tales of meeting Tolstoy in Russia and swimming with Rupert Brooke, the idealistic English poet,” writes O’Sullivan Greene, who spent a summer working in a supermarket in Boston on a J1 Visa in 1987 and participated in a management training program in New York in 1990 and ’91. “In short, Leslie represented everything to which he aspired.”

He continues, “Ironically, and with unintended insight, Scott viewed Leslie as ‘a young Englishman of the governing classes when the sense of being one must have been … like the sense of being a Roman citizen.’ As a proud Irishman of Anglo-Protestant heritage, Leslie would have protested. However, he did see himself as part of a governing class. A fervent believer in Home Rule as a solution to the Irish question, he advocated for a parliament in Dublin attending to domestic affairs, with Ireland remaining loyal to the King and continuing as part of the British Empire.”

Fitzgerald, who apparently followed such events closely, was sympathetic to the Home Rule cause, too, but also referred to the 1916 Rising in Dublin and its doomed separatist leaders as “mystical” and “romantic.”

He wrote positively about and recommended to others Leslie’s books. Writes O’Sullivan Greene, who has worked in his business career in Ireland, Britain, France and the U.S., “Scott found ‘The End of a Chapter’ to be ‘very entertaining.’ Written while he was recuperating in hospital, Leslie addressed the key geopolitical, cultural and religious trends emerging in advance of the war and the state of the British Empire and Ireland.”

But it was “The Celt and the World,” which explored the historic relationship between the “underdog” Celt and the “materialistic” Teuton that most resonated with Fitzgerald, and he was inspired to write an admiring review of it.

O’Sullivan Greene, who was invited to present his first book “Crowdfunding the Revolution” to President Michael D. Higgins, offers a “fresh insight” into the life of Fitzgerald. He searches in particular for the reasons that the novelist’s interest in things Irish, as evidenced not least by certain references in “This Side of Paradise,” had disappeared by the time of the publication of his most iconic work, “The Great Gatsby,” five years later; and he argues that the creation of the latter novel is the “story of American identity as much as the American Dream.”

O’Sullivan Greene told the Echo, “Underpinning Fitzgerald’s brilliant but turbulent life was his complex, evolving and surprising relationship with his Irish identity. From childhood shame at being ‘common’ to a patriotic immersion in Irish literature and revolutionary politics at Princeton. But the shame never went away, reinforced when the poor boy found he could not marry the rich girl.”

He added, “Fitzgerald tried to escape it, first through his imagination as a boy and self-invention as a young man, and then in his writing and self-destructive lifestyle.”

Patrick O’Sullivan Greene

Date of birth: Jan. 23.

Place of birth: Killarney.

Residence: Beaufort, Killarney.

Published works: “Gatsby - Death of an Irishman: F. Scott Fitzgerald and his Search for Identity” (2025); “Revolution at the Waldorf: America and the Irish War of Independence” (2023); “Crowdfunding the Revolution: The First Dáil Loan and the Battle for Irish Independence” (2020). For more biographical information, see here.

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

Much of my writing is done at home looking out on Carrauntoohil, Ireland’s highest mountain, and the magnificent MacGillycuddy Reeks. I also write in two great coffee shops in Killarney, Lir and Noelles, fueled by expresso and hot chocolate. I enjoy writing in the quiet of home as much as in the bustle and noise of a busy retail environment.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

The same advice given to me by a journalist: Just write! I had no experience or desire to write a book, but I came across an important and forgotten part of the Michael Collins story that needed to be told so I needed to learn the craft; attend short creative writing seminars even if you are writing a non-fiction book, expand your vocabulary (I learned seven alternatives to the word “significant,” a word I used continually when in business), and look at the sentence structure and techniques of other writers. Most of all, understand that you are delivering a message not a summary. Less is more!

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

“The Grapes of Wrath,” “Catch-22” and “Eagles at War” (part of Ben Kane’s Roman Historical Fiction series)

What book are you currently reading?

Claire Keegan’s “Small Things Like These.”

Is there a book you wish you had written?

I would like to write a book like Bill Bryson’s “One Summer: America, 1927,” but about New York during the turbulent summer of 1919.

Name a book that you were pleasantly surprised by.

“The Great Gatsby” — There is so much more to the book on second, third and ongoing readings, in particular in audiobook versions.

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

F. Scott Fitzgerald, of course. I am not sure I would like him, but it would be great to get inside his mind more.

What book changed your life?

No single book changed my life, but I remember as a child crying on the death of Robin Hood in a book whose name I cannot remember.

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

The Gap of Dunloe in Beaufort, Killarney, is magical at all times of year.