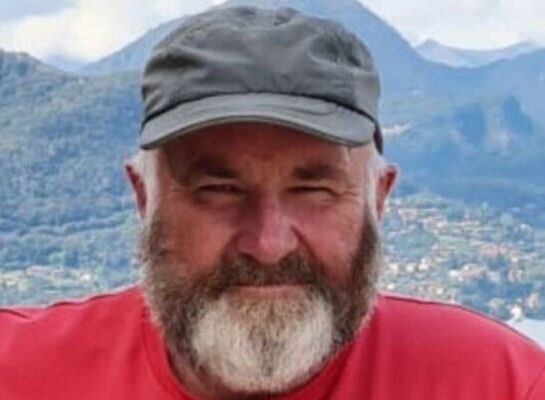

The most respected and significant person of my boyhood in Mountmellick, Co. Laois, was E. J. Breen, who taught in the Boys’ National School. He was always addressed as Mister Breen. Behind his back he was referred to as “The Sheriff.”

Mister Breen’s height of over six feet, his square face, his rimless glasses, his crown of grey hair, his locally tailored suit, his five different neckties and his polished shoes projected a selfhood totally at ease with itself.

My closest encounters with Mister Breen took place in the classroom. He was a strict master. As was accepted practice in those days, he used the cane or stick or rod—"an bata” in Irish--as punishment for a variety reasons: sloppy work, homework not done, lateness, talking in class, misspelling.

The first business after roll call each morning was a test of the previous night’s spelling assignment. Each boy left his desk and stood with his back to the classroom wall. With an bata in hand, Mister Breen circled the room and asked each boy to spell a word. If he made an error, even in the middle of the answer, Mister Breen interrupted. “An lamh” -- the hand -- he said, and the sinner held out his hand and received four whacks on the palm and fingers.

For my homework one night the words “high” and “height” were on the spelling list. I spent time figuring out how to remember one from the other. The next day Mister Breen asked me to spell “high.” “H-e-i,” I began. “An lamh,” he said. I felt aggrieved because the two words were so alike, so aggrieved that I told my uncle Paulie what had happened.

“Ah, the Sheriff!” Paulie said. “I was in his class when I was your age. One day he asked us which teacher in the school had only four fingers on his hand. I stuck up my hand. ‘Yes, Paulie,’ Mister Breen said. ‘Sir, all the teachers have only four fingers; they all have thumbs and a thumb is not a finger. Mister Breen walked down to my desk and said, ‘That’s very good, Paulie. You will be a great detective when you grow up. Now, tell the class how you spell “thumb.”’

In his Midlands accent, Paulie spelled, “T-u-m, sir.”

“An lamh,” said Mister Breen.

Mister Breen’s strictness and his use of the stick might beg the question, Why did his students respect him so much? Probably because Mister Breen made his rules clear to each new class at the beginning of the year. He himself adhered strictly to these rules, and his students were safe within their confines. He never raised his voice in anger.

And when he used the stick there was never a glint of cruelty in his eyes. He did not show favoritism. Nor did he hold up a child’s behavior as an example to be followed or avoided. It was this classroom stability that sheltered us students from the fear of angry eruptions from our teacher.

When Mister Breen walked in the town, word of his approach preceded him. Men who had not traveled far in life because of physical, academic and intellectual poverty, sometimes combined with alcoholism, and who hung out in shop doorways and on street corners, hid when their former teacher approached. They did not hide because they were afraid of him; rather, they did not want him to see their sorry states. When Mister Breen did encounter an alcoholic past student, he spoke quietly with him, inquired about his parents and siblings, and when leaving, was sometimes seen slipping money with his parting handshake.

***

Back in the day when the Church took over the suppression of Ireland from the English, men who aspired to teach in the National School System were educated in Saint Patrick’s College in Drumcondra in Dublin. Founded in 1875 by the Marist order, it was soon taken over by the Vincentians, who operated the college as a lay seminary. Bells announced religious services, meals, classes, lights out and reveille. One of the obligations laid on the graduates was that they assist the priests in the parish schools in which they would teach. The parish priest—the pastor--was the manager of the school, and he hired and he fired.

In Mountmellick, Mister Breen was the only teacher who assisted our pastor, Father McCluskey. McCluskey had the personality of a blackthorn bush in wintertime—leafless, sloeless and bristling with thorns. He lived in the largest house in the town, a three-story residence with six steps up to the Georgian front door. Virulently anti-English, he had been jailed during Black and Tan days when a pistol was discovered in his house. During the Second World War, he dispensed from the pulpit the news from Europe, glossing it with his support of Germany and his satisfaction over English defeats.

Father McCluskey decided to add an extension to the parish church, one his parishioners considered unnecessary. Years of Sunday sermons morphed into appeals for the Church Building Fund. At Christmas, we were reminded that the new wing would be a step up for Jesus from the stable in Bethlehem. Week after week, the pastor droned on, but it was Mister Breen who did most of the heavy lifting to raise the necessary money.

After many years, the new wing of the church was completed. It was consecrated following a bagpiped procession through the town led, no less, by Prime Minister Eamon de Valera and President Sean T. O’Kelly. Afterward, they were invited to a celebratory feast along with other notable people. But Mister Breen was not included; he was a Labourite and the pastor supported Fianna Fáil. Many people in Mountmellick felt a stab of disappointment when they heard of this snub.

With the church’s new wing out of the way, the local chapter of the Catholic Young Men’s Society decided to build a cinema in Mountmellick. The CYMS was a lay, social, quasi-religious and sporting organization founded in Limerick in 1849. Mister Breen, who belonged to the CYMS, was a driving force behind the new cinema. It would replace the old Owenass Hall, which was no longer considered safe for large groups. For years, Mister Breen had been using that hall, with its wooden chairs and one projector, as a semi-nightly picture house as well as for Sunday matinees.

When I was about ten, my friend Paddy Walsh and I were ejected from the old hall by Mister Breen for talking during a film. We had to stand with our backs to the outside wall as passers-by taunted us. “Did the Sheriff throw ye out? Maybe next time he’ll hang ye from a telephone pole!” We were soon allowed back in.

For the cinema, Mister Breen helped raise funds by way of dances and raffles and card tournaments at Christmastime, with a turkey as first prize, two ducks as second, and two hens as third. The cinema was built in twenty months and was a great success. It had two projectors, 800 plush seats, a balcony and a stage. The CYMS elected Mister Breen as manager.

The esteem in which the town held Mister Breen was demonstrated on the evening David Lean’s “The Sound Barrier” was shown. Before the movie began, Mister Breen stepped out on the stage and silence immediately descended. In a two-minute non-amplified talk he explained what the sound barrier was and the aerodynamics surrounding the effort to break through it. When he left the stage there was an energetic round of applause.

Today, nearly 75 years later, the building, now called the Mountmellick Community Arts Centre, is still in use.

***

Mister Breen had been teaching in the Boys' School for almost 30 years when the principal, Mister Bennet, retired. Because Mister Breen was so respected as a teacher and as a County Councilor and because of his efforts on behalf of the parish and the town, everyone assumed he would get Bennet’s job. What they did not count on was the bitterness of Father McCloskey, who had never been known to utter a word of praise about Mister Breen.

McCloskey did not promote him. I often heard it said that being cast aside so publicly broke Mister Breen's spirit.

© 2025 by Glanvil Enterprises, Ltd.

Tom Phelan is the author of “We Were Rich and We Didn’t Know It: A Memoir of My Irish Boyhood,” as well as many novels set in Ireland. You can read more about him and his work at his website here. www.tomphelan.net.