“Public Warned Not To Attend Illegal Dance This Weekend,” a Leitrim Observer’s recent article’s headline read. It was in reference to a thing called “‘The Devil’s in the Dance Hall’ Grand Dance,” a series of shows that featured Edwina Guckian & The Gralton Big Band and lit up my social media feed this week. The band, led by Guckian, included a rake of top flight traditional artists like Cathy Jordan, Ryan Molloy, Stephen Doherty, David Doocey, Matt Berril, Jim Higgins, Conor Caldwell, John Carty, and Ben Castle, and visited Leitrim, Galway, Mayo, Clare, and Donegal. In doing so, they made a mockery of the Public Dance Halls Act of 1935. “Expect swing, trad, foxtrots, slow sets and short skirts. Expect sean nós, shim-shamming, lindy hopping, set-dancing, surprises and scandal,” the promo read. “[C]ome dressed in your finest 1930s gear, polish up your brogues, wear your boldest lipstick and make it a night you’ll never forget, dancing with the devil in the dancehall.”

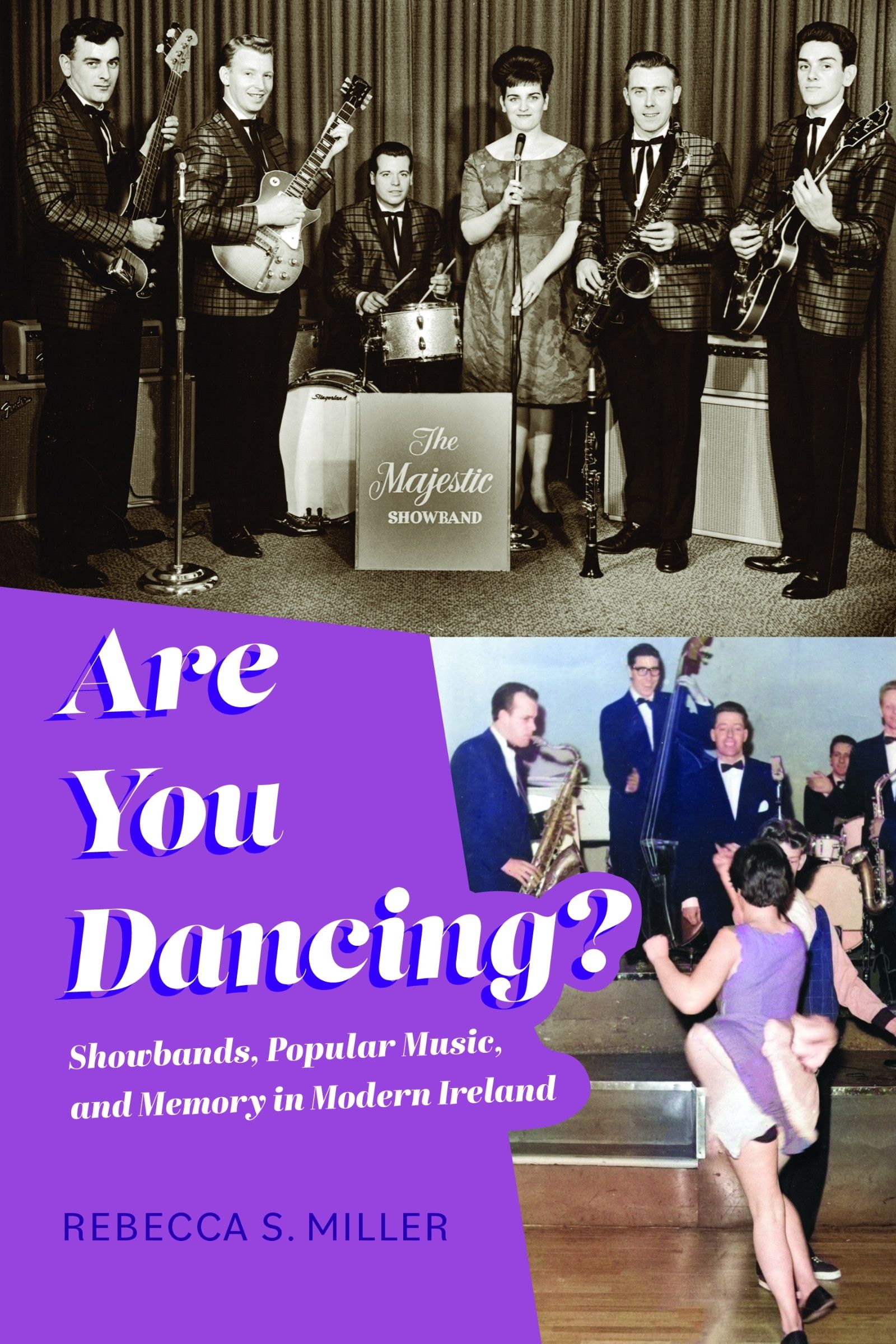

Instinctually, you’re probably thinking “down with this sort of thing,” but from the short clips I saw, the shows were a major success, exploring the sounds and dances of a noteworthy moment in Ireland’s cultural history. And it was a particularly fitting thing to see this week, given I’m just after reading Rebecca Miller’s “Are You Dancing: Showbands, Popular Music, and Memory in Modern Ireland.” An absolutely fabulous book that I think this column’s readers will be interested in, its aim is “to fill in the gap of knowledge surrounding Irish popular music from roughly 1925 to 1975 and, in doing so, balance the often unquestioned assumptions that Irish dance bands and the later showbands were ‘musical deserts’ – aesthetically and culturally valueless and, indeed, worthy of forgetting.” Sound interesting? If so, read on….

Miller is no stranger to traditional music, and no doubt many readers of this column already know her work. In the 1980s, she directed the Irish Arts Center’s folk-arts programming and oversaw its popular annual traditional music festival at New York’s Snug Harbor Cultural Center. She also co-produced and wrote the excellent documentary “From Shore to Shore: Irish Traditional Music in New York City” (1993), and contributed liner notes to albums such as “The Humors of Glin,” Martin Mulvihill’s cassette-only 1986 release. Beyond this, she has authored several influential scholarly articles on Irish music, including “Our Own Little Isle: Irish Traditional Music in New York” (1988) and “Irish Traditional and Popular Music in New York City” (1996).

Her work has earned broad recognition. She received a Fulbright Fellowship and carried out significant research in the Caribbean that led to her book “Carriacou String Band Serenade: Performing Identity in the Eastern Caribbean,” an outstanding study of that island’s string-band tradition. A Whiting Fellowship supported her fieldwork in Ireland for this project, and in 2018–19 she held a fellowship in Irish Studies at the National University of Ireland, Galway.

But Miller actually started working on this project in 1988. The fruit of her decades-long labor is a social history of showbands that looks to deconstruct a number of the genre’s common critiques, like the ideas that these groups were too imitative, were inauthentically Irish, and that their commercial nature robbed them of artistic integrity. She begins the story by drawing a parallel between the emergence of céilí bands and the concurrent development of dance bands/orchestras at the time of the Public Dance Halls Act. From there, she’s able to tease out how the artistry that shepherded the transition from sit-down dance bands to showband began.

Her chapter on Hugh Toorish, the Carlton Clippers and fit-up troupes was an especially illuminating follow up, because it explored an important transitional moment in the genre’s history. There, Miller looks at how modern dress, mannerisms and on-stage dynamics became both expressions of youth and symbolic of showband culture. The chapters on entrepreneurship and marketing outline the ascendency of these ideas among showbands and were equally compelling. Miller’s treatment of gender is also very strong. Her documentation of women like Mildred Beirne and Eileen Kelly is as fascinating as her writing is about the pressures women faced in the largely male showband world.

In general, I found myself particularly interested in the way Miller detailed aspects of Irish culture that are almost never touched on in the discourse around traditional music. I was surprised by the number of traditional musicians whose lives intersected with showbands. I think, for example, of the Majestic Showband, which included Martin Mulhaire and Mattie Connolly, a couple of great traditional musicians. I was also interested in the perspective of folks like Jack Coen and Charlie Lennon, both of whom share insight into the showband phenomenon from a traditional musician’s perspective. They’re fascinating takes.

“Are You Dancing” is an important book about music in Ireland. No, it’s not about traditional music (as is the normal purview of this column), but the story it tells of the showband era is a crucial part of 20th century Ireland – it’s a history that many lived, some still remember, and is very much worthy of knowing about. Miller does a very fine job of integrating field methods into her archival work and because her writing is sophisticated and nuanced, the book feels lively and well-grounded. Great stuff! Recommended to anyone who remembers the showband era and those with an interest in Irish music history’s bigger picture. “Are You Dancing” is published through Indiana University Press.