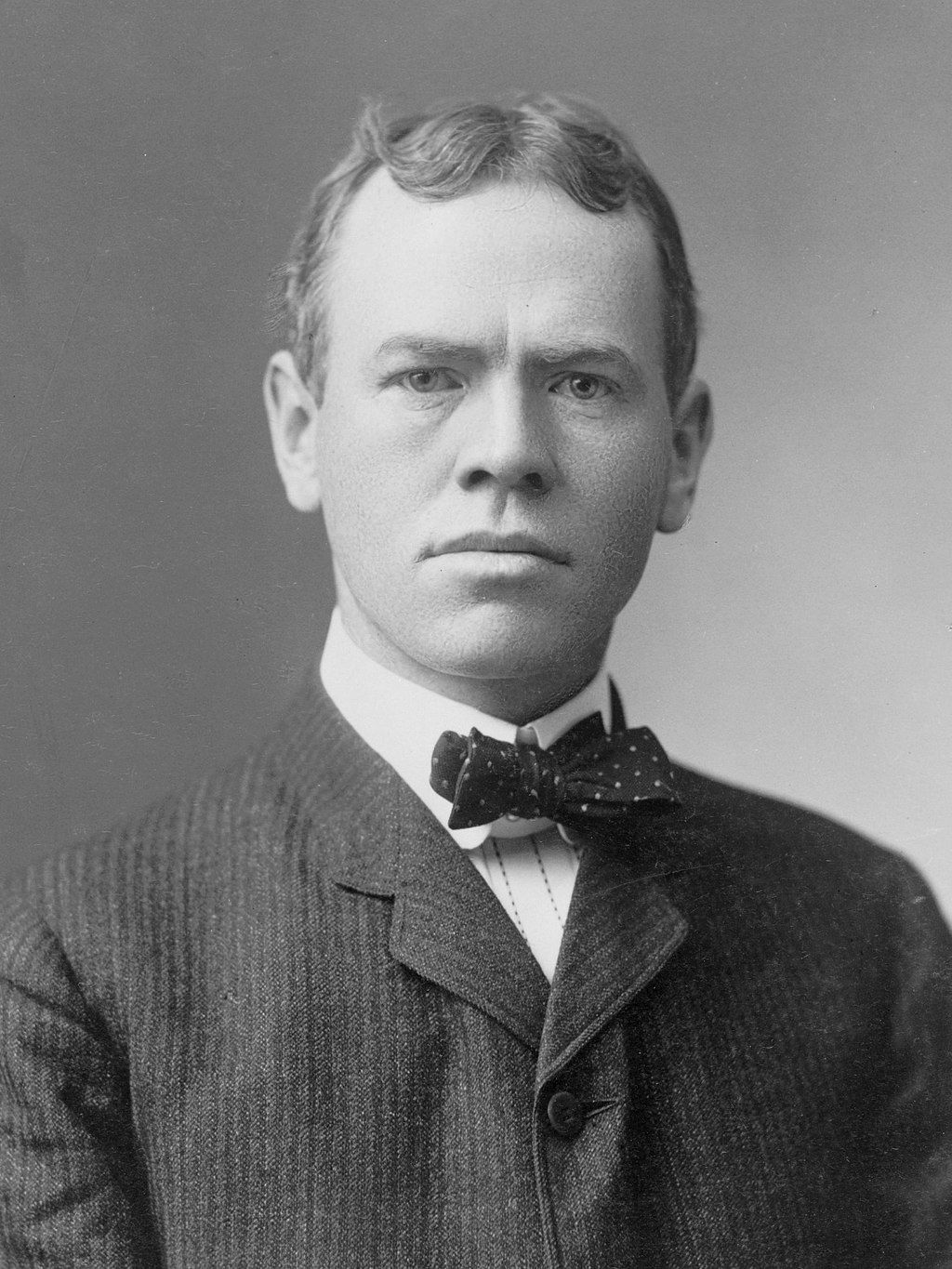

In 1896, with the revival of the Olympic Games, James Brendan Connolly, the son of immigrants from the Aran islands, became the first Olympic champion in more than 1,500 years. Connolly, however, was much more than just a great athlete. He was a war veteran, journalist and the author of more than 25 novels and 200 short stories. His close friend President Theodore Roosevelt paid him the highest compliment saying, “If I were to pick one man for my sons to pattern their lives after I would choose Jim Connolly."

Connolly was born in South Boston Oct. 28, 1868. One of 12 children and the sixth of 10 sons, his father was a fisherman, while his mother raised the children and translated Gaelic poetry. He recalled his South Boston area of his youth as being obsessed with athletics. Among his childhood friends were six future professional baseball players. Growing up, he admired John L. Sullivan, the Boston Strong Boy who became world heavyweight boxing champion and arguably the first American sports superstars.

As was usual for a young man from a working-class family, Connolly never attended high school. After working as a clerk in a Boston fraternal benefits society that offered insurance, he joined the Army Corps of Engineers in Savannah, Ga., where he founded a Catholic sports club, wrote a sports column for a weekly newspaper and established a bicycling business. In 1890, he won the national triple jump championship. Despite not going to high school, he passed Harvard’s entrance exam in 1895 and was accepted to study in the fall.

Connolly learned of the revival of the Olympic games and decided to travel to Athens and compete there. Europeans were expected to dominate all the events, and the United States fielded only a dozen athletes, mainly from Harvard and Princeton. To qualify, all the Americans had to do was fill out an entry form and pay their way across the ocean. Connolly was determined to join the team of 1896. He had just been accepted to Harvard and sought a leave of absence so that he could compete in the first modern Olympiad, but administrators refused his request, and Connolly subsequently withdrew from Harvard. Connolly was so angered by Harvard’s refusal to grant him leave that he turned down and honorary doctorate the university offered him in 1949.

Connolly almost never made it to Athens. His trip started with a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to Naples, Italy, where Connolly’s wallet was stolen and later recovered by police. The police wanted him to press charges against the thief. Taking time to do that would have made him miss the American contingent’s train and he was forced to flee the police and narrowly caught the already departing train.

At their first breakfast in Athens, Connolly looked at a program and only then realized that the Greeks went by a different calendar. The track and field events began that day, starting with Connolly’s top event, the triple jump.

At the time, the triple was either a hop, step and jump or two hops and a jump. The last triple jumper to go off, Connolly noticed that three competitors had done a hop, step and jump, while the rest did two hops and a jump.

“I came to Athens all set to do a hop, step and jump; yet in that stadium that day, in contest for an Olympic championship, I shifted at the last moment to two hops and a jump, which I hadn’t jumped since a boy against other boys,” Connolly wrote.

In that first modern Olympics, triple jump competitors were not allowed to walk off and measure their approaches and were not told their results until the end of the competition, which increased the pressure on the athletes. He later recalled, “I was standing between Prince George [later King George V] of England and Prince George of Greece, and the personal magnetism of these two gentlemen was so strong that I said, ‘Here’s to the honor of County Galway!’ and I jumped.”

Connolly finished first by a full meter and received the silver medal awarded to first-place finishers at Athens 1896. Second-place finishers received bronze medals, the only other medals awarded there. He tied fellow American Robert Garrett for second in the high jump (winning the bronze medal) and was third in the long jump but won no medal. Back home in Boston, Connolly received a hero’s welcome and a gold watch from the citizens of South Boston.

In 1898, the United States declared war on Spain and Americans fought in Cuba. Connolly enlisted in the army when the war began, serving in the Irish Ninth Regiment of Massachusetts and fighting up the legendary San Juan Hill. He wrote to his family in Boston, vividly describing his war-time experiences in a series of letters that were then published in the Boston Globe. In these dispatches, he developed the vivid first-person narrative style that would earn him praise as a writer and journalist. Connolly returned to the Olympics at Paris 1900 and finished second in the triple jump, bringing home the bronze medal.

Himself the son of a fisherman, Connolly decided to write stories about the fishermen of Gloucester, Mass. Scribner’s published them as articles and then as a book. Connolly would continue to write about the sea. Scribner’s and Harper’s commissioned him to write about fishing trips in the Arctic. He wrote about whaling trips, schooner races and a host of other maritime adventures. Impressed by Connolly’s prose, President Roosevelt gave him permission to board any American navy ship any time anywhere and stay as long as he wished, which furnished him material to publish several pieces on the United States Navy.

Connolly was hailed as “America’s best writer of sea stories” by Joseph Conrad and his writing was also admired by T.S. Eliot. In his autobiography: “Sea Borne: Thirty Years Avoyaging,” Connolly talked about his family’s Irish roots, “As far back as my father and mother knew, their people came from seafaring stock. They were Aran Islands folk; islands that lie off the west coast of Ireland. It is a rough coast, and the Arans are little isles and almost solid rock, which was one reason why so many men of those isles took to the sea. The lack of arable land left the sea as their best chance for a living.”

He covered the 1908 London Olympics as a journalist, bringing an Irish eye to his coverage of the British. Connolly's manuscript entitled "The English as Poor Losers" attacked Anglo-Saxon anti-Irish bigotry as well as the British sense of false superiority.

Connolly ran for Congress on his friend Teddy Roosevelt’s Bull Moose ticket in 1913. Though he was defeated, Connolly ran 2,500 votes ahead of the other Bull Moose candidates on the ballot. In 1914, he became Collier’s correspondent in Mexico, reporting on the United States’ attack on the city of Veracruz. During the first World War he wrote as Collier's naval correspondent for European waters. He published a book about an American U-Boat hunting destroyer fleet that sailed out of Cobh in 1917.

In 1921, Connolly was named Commissioner for the American Committee for the Relief of Ireland. His task was report on the story put out by London that American Relief money was being spent for arms and munitions for the Irish Republican Army. He was able to expose this anti-Irish claim as fraud. The Black and Tan War was at its height while he was in Ireland and on his return to Boston, he exposed the atrocities of the Tans in a series of articles for the Hearst Press.

Connolly lived to be 88, dying on Jan. 20, 1957. When he passed, journalists around the country eulogized Connolly, including Arthur Daley of the New York Times, who called him “An Olympian to the End.” Today a statue in South Boston honors the Irish American who became the first Olympic champion of the modern era.