A President from the great state of New York serving one of his two nonconsecutive terms in the White House. A precocious political talent running for Mayor of New York City. Progressive ideas about taxation motivating the support of voters. A well-connected, well-funded candidate trying to consolidate support in a crowded, three-way race. Rumors of a job in Washington, DC being dangled in exchange for an exit.

The year, of course, is 2025. But it was also 1886, when, during Grover Cleveland’s first term, William Grace, the first Irish-Catholic elected mayor of New York City, did not run for reelection. Running to replace Grace were Republican Teddy Roosevelt, then only 28 years old, Democrat Abram Hewitt, and Henry George of the short-lived United Labor Party.

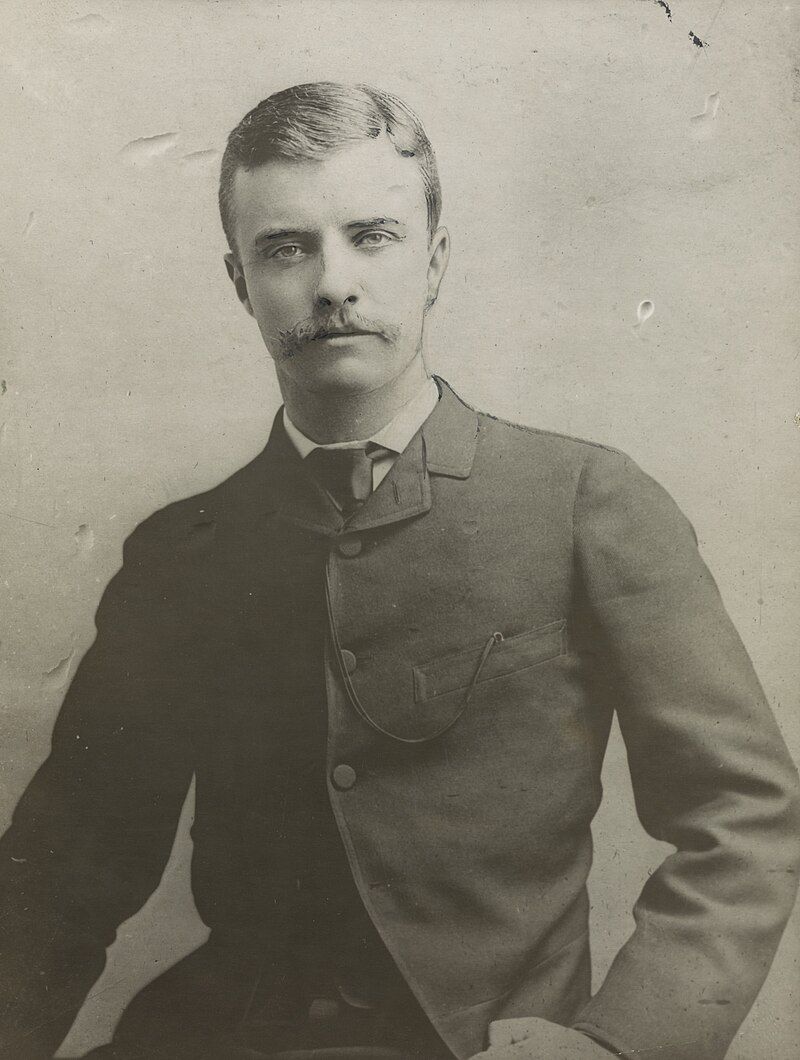

George was famous for the radical economic ideas found in his 1879 book “Progress and Poverty,” which argued that a single-tax on land use could combat the vast wealth inequalities of the day. George was not Irish, not Catholic, and not from New York. But his ideas were a major influence on the saintly, one-armed agitator and pride of Mayo, Michael Davitt. And during the Davitt-led Land War, George had been the Dublin-correspondent for Patrick Ford’s New York-based Irish World newspaper. Besides Ford, George found a champion in Fr. Edward McGlynn, the populist pastor of St. Stephen’s parish on 28th Street, who was suspended and eventually excommunicated for campaigning for George. In an informative article about the election published in the City Record back in 1993, Richard Brookhiser claimed that the Democrats offered George a seat in Congress if he chose not to run. George turned them down and stayed in the race.

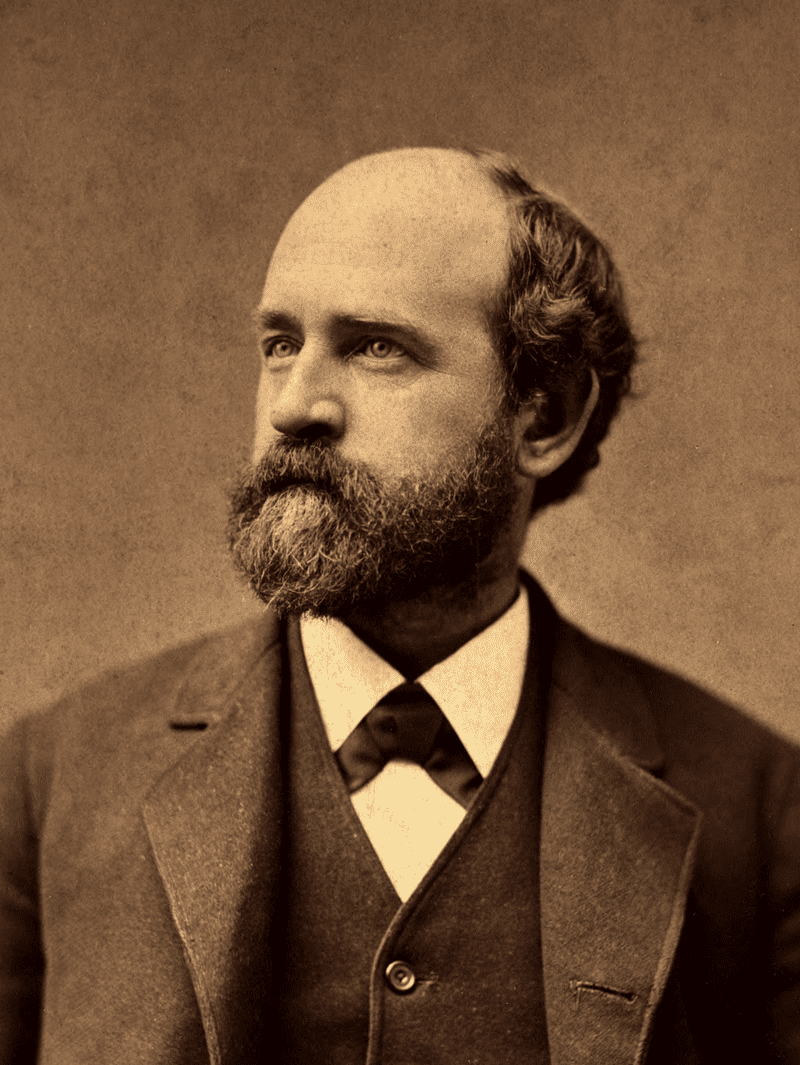

Henry George, author of “Progress and Poverty,” had much high-profile support in the New York Irish community.

In his excellent book “Machine Made,” Terry Golway explains how Richard Croker, the Tammany chief, knew he needed a candidate to counteract George’s popularity with the working-class, a candidate who could appeal both to Irish laborers and to the WASP businessmen in the party. The choice was Abram Hewitt, a former Congressman and Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, an industrialist and a philanthropist, the son-in-law of Peter Cooper, founder of Cooper Union college. Golway paraphrases the Irish-born Tammany mouthpiece William Bourke Cockran, who explained how Hewitt was “a friend of working people” since “after all, five thousand people worked for Hewitt, and they never had cause to go on strike.”

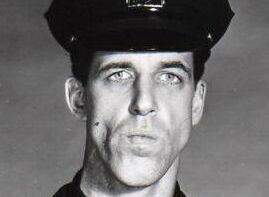

No one on the Republican side could spin such claims about Roosevelt. He had inherited great wealth, graduated from Harvard, and published a history of the War of 1812. He entered politics with relish, won a seat in the state assembly, but frowned on his working-class Irish-American colleagues from New York City, describing them in a letter as “a stupid, sodden, vicious lot…equally deficient in brains and virtue.”

According to Brookhiser, Hewitt did not malign Roosevelt, but instead, “treated him as a fine young man who had a brilliant future ahead of him but warned that every vote he took now was in effect a vote for the hellish George.” Not surprisingly, “Hewitt’s strategy from the outset was to demonize” George by associating his ideas with “anarchists, nihilists, communists, socialists, and mere theorists,” with “the horrors of the French Revolution and the atrocities of the [Paris] Commune,” with “the dreadful consequences of doctrines which can only be enforced by revolution and bloodshed.” Despite the attacks, a Tammany operative reported: “We can get the men to vote as we want them to, except for Mayor. We can’t move them there. They have got into their heads to vote for George and there it sticks.”

On Election Day, after seeing some early returns, the Republican party boss, Thomas Collier Platt (dubbed “Lean Rat Platt” by the poet Vachel Lindsay) sent out the call to vote for Hewitt, not young Teddy. The final tally was 90,522 for Hewitt; 68,110 for George; and 60,435 for Roosevelt.

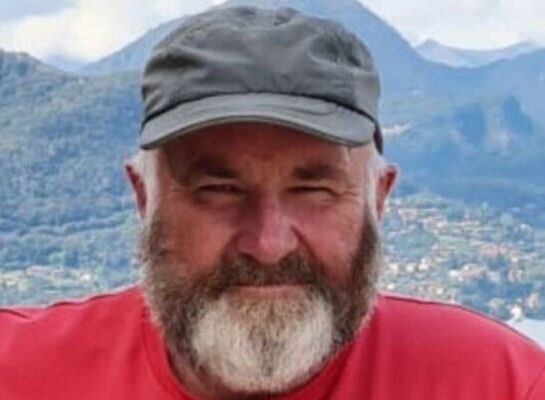

During his single term as mayor Hewitt got on the wrong side of Croker when he declined to view the St. Patrick’s Day parade. Brookhiser also notes that Hewitt “cracked down on gambling, whoring, and saloons that broke the blue laws,” none of which would have endeared him to Tammany Hall. In 1888, Croker engineered the election of his protégé Hugh Grant. Grant was 30 years of age when elected, and remains New York City’s youngest ever mayor.

Though he was denied the footnote of being New York’s youngest mayor, Teddy Roosevelt did all right in the end: in the 1890s he would be NYC Police Commissioner, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, popular hero of the Spanish-American War, Governor of New York, and Vice-President. When President McKinley was assassinated in 1901, Roosevelt became the youngest person to serve as U.S. President.

As for George, despite the second-place finish in 1886, the enthusiasm for his candidacy rippled not only across the country, but across the Atlantic. Golway reports: “In London, Friedrich Engels took time from editing the works of his late partner, Karl Marx, to hail the turnout for George as ‘epoch-making.’” George would try running again in 1897, but died from a stroke four days before that election.

Hopefully, this sketch of the 1886 election suggests some obvious parallels with the current one: George’s progressive economic policies and advocacy for Irish land reform bears some resemblance to Zohran Mamdani’s democratic socialism and advocacy for a free Palestine; Hewitt’s scare tactics sound very much like some of Andrew Cuomo’s rhetoric; the attempt to bribe George with a seat in Congress is echoed in recent reports that President Trump offered Eric Adams a job in his administration so that he could gracefully exit the race.

But there are also important differences between the two elections. George was running as a third-party candidate; Mamdani won the Democratic primary and has been endorsed by many party stalwarts. Hewitt was running with the full support of the Democratic machine; Cuomo is not. Roosevelt had a functional, viable Republican machine behind him; Curtis Sliwa does not. And while the Irish, either as Tammany’s leaders, or as an ethnic voting bloc, played a central role in 1886, let’s be honest: the Irish haven’t had much say in who runs City Hall in many, many decades.

So what’s the point of this, or any, historical analogy? We’ve all heard some version of George Santanaya’s famous line: “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” And maybe some of us know the line from Marx, riffing on Hegel, about how history repeats itself: first as tragedy, then as farce.

But even so, many readers of this article may be suffering from a condition we might call historical-context-fatigue, as so many commentators have spent the past decade continually and constantly using the events of 1930s Germany to predict the fate of 2020s America. For my money, the Gilded Age (which began with Hewitt’s botched handling of Samuel Tilden’s campaign for President in 1876, which included Cleveland’s two nonconsecutive terms, which encompassed George’s whole career as a public intellectual, and which ended with the assassination McKinley and the ascension of Roosevelt) is a much more useful local context for trying to understand current events. Because surely, the past can illuminate the present.

And the main lesson the election of 1886 teaches is that we should not be surprised if both institutional forces and individual voters fearing radical social and economic change band together at the last moment of the election to protect the status quo. Therefore, an Andrew Cuomo victory is still very much a possibility. But we should also be open to the possibility that the present moment has the potential to create unprecedented history of its own. Hence, Zohran Mamdani could very well prevail. And if he does, it will be worth considering if it’s a sign that a new Progressive Era, similar to, but distinct from the one Teddy Roosevelt initiated, is beginning.

History can be a flickering lamp, but it’s not a crystal ball.

Dr. Stephen Butler is Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program, New York University.