The foundation of any country’s justice system is justice itself. Justice requires that individuals receive fair, impartial, and reasonable treatment in accordance with the law. The law, then, must provide assurances to individuals that when allegations of harm are made, the accuser and the accused receive a morally right result as warranted by their actions.

Accordingly, when a bill, such as the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation ) Bill, the “Legacy Bill," vitiates the fair, impartial, and reasonable treatment of victims by shielding the accused from judgment and denies victims access to the courts, it becomes an injustice.

The Legacy Bill was introduced in the House of Commons on May 17, 2022, proposing to end all civil and criminal legal proceedings filed against British soldiers, police, and paramilitary organization members attributed to their actions during the Troubles.

It also prohibits any future filings against any accused person. Inquests launched into unlawful actions committed by soldiers, police, or paramilitary members during the Troubles, not including those nearing a conclusion, would terminate. The Legacy Bill establishes the Independent Commission for Information Recovery and Reconciliation, the “ICRIR,” charged with reviewing unlawful deaths occurring during the Troubles and publishing their findings.

The Legacy Bill provides immunity from prosecution for persons committing unlawful offenses during the Troubles on the condition that they provide the ICRIR with incriminating information about their offense. Thus, giving perpetrators amnesty for their crimes while barring any criminal or civil legal recourse in the courts of law for the victims or families.

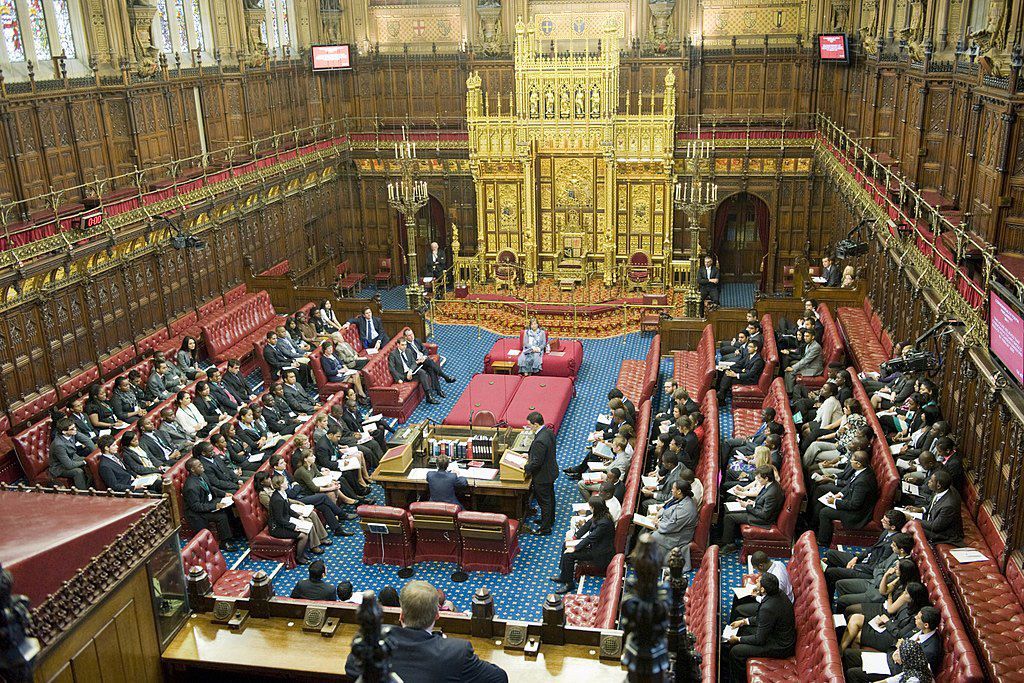

After the initial passage of the Legacy Bill in the Commons, it moved to the House of Lords where it lingered for some time. In the House of Lords, the Peers amended the Bill to remove two controversial provisions. The first amendment removed the ICRIR’s ability to grant immunity from prosecution to those responsible for the unlawful deaths and tragedies committed during the Troubles. The second amendment inserted a requirement that the ICRIR conduct its reviews in accordance with criminal justice processes and procedures. Some 129 amendments were added to the Legacy Bill in the House of Lords, with the majority being put forth by the British government, several of which attempted to soften some of Bill’s highly contested provisions.

Notwithstanding, the British government strongly opposed the Lord’s removal of the immunity provision and the insertion of the criminal process and procedures requirements. The Bill now stands ready for a September 5th vote in the House of Lords following its return from the House of Commons, which reinstated the immunity provision and removed the criminal process and procedures requirement by a 292 to 200 majority vote.

In a public response released in mid-July of this year, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Chris Heaton-Harris MP, outlined the next steps towards passage of the Legacy Bill. In it, the Secretary makes clear that the British government will not agree to the amendments made by the Lords to remove the immunity provisions and insert criminal process and procedural requirements. The Secretary’s argument for keeping the Bill as drafted was that it will produce the “…greatest volume of information, in the quickest possible time…,” and give “…the ICRIR robust powers that will facilitate the information recovery process….”

The Secretary predicates the British government’s support of the current version of the Bill on the assumption that recovery of information in a quick fashion will itself satisfy the victims and families and serve as a substitute for the current pace of justice.

To illustrate the resulting injustice, assume that forty years ago a person was severely beaten or killed in what was an unlawful action. Forty years later, evidence is gathered by a commission to establish who the perpetrator was, and if they acted under government authority. The perpetrator, forty years on, learns about the investigation into his unlawful act and that he can receive immunity from this investigative commission.

He then approaches the commission declaring, “I did it.” The perpetrator will not, however, be prosecuted for their crime. Instead, the information will appear in a report establishing that the perpetrator committed the crime and was acting under government authority.

Prosecutors could not bring charges even if the evidence were obtained outside of the commission’s investigation. Victims and families are then barred from filing civil lawsuits against the perpetrator or the government because he was granted immunity for implicating himself in an unlawful act. In the end, the perpetrator escapes prosecution, the victims and the families are handed a report, and access to justice is denied.

Condemnation of the Legacy Bill is broad. The Bill has been denounced by all five political parties in Northern Ireland. In June, the President of Sinn Féin, Mary Lou McDonald, openly contended that the Bill would close the door on victims’ access to justice in a court of law.

Sir Jeffrey Donaldson, leader of the DUP, asked the Prime Minister not to move forward with the Bill maintaining that a substantial majority of victims and families, who suffered significantly during the Troubles, have rejected the language set out in the Bill.

Donaldson also characterized the immunity provisions as an insult to justice. The Taoiseach of Ireland, Leo Varadkar, observed that granting immunity to former soldiers and paramilitary members, who may be identified as committing crimes, is wholly the wrong approach.

He speculated that should the Legacy Bill become law, consideration will be given on whether an “interstate” case should be brought against the United Kingdom. The Irish government would have the ability, also called “standing,” to bring a case in accordance with Article 33 of the European Convention of Human Rights, the “ECHR”.

If filed, it will be heard in the European Court of Human Rights. The key violations likely to be alleged are violations of ECHR Article 2, Right to Life, and Article 3, Prohibition of Torture. In a research briefing published in mid-July of this year by the House of Commons Library, it noted that the European Court of Human Rights has previously held that the granting of amnesties [immunity] by a State is contrary to its duty to provide for the effective investigation of deaths subject to the parameters of Articles 2 and 3 of the ECHR. Nonetheless, the British government believes that the Legacy Bill’s provisions are compatible with the ECHR.

The United States Constitution provides its citizens with the right to Due Process of law, including access to our courts. Although, at times, our justice system may not be as speedy as we wish, we have a right to justice nonetheless. The Commons Research Briefing also noted that, as of May 2022, the Police Service for Northern Ireland, the “PSNI," had a legacy caseload of approximately nine hundred cases involving 1,200 deaths with most of the cases remaining unsolved.

Secretary Heaton-Harris stated in his July 18, 2023, government response that, as “…a Government it is our responsibility to establish the best practical way to deliver better outcomes for many more people affected by the troubles than the current system does.” Implicit in this contention is that the PSNI Historical Enquiries Team has nine hundred legacy cases pending, and efforts to allow the families and victims to seek a judicial resolution of these cases should be abandoned and substituted for expediency without justice.

In its place, a report from the ICRIR will be handed to the victims and families. Unlike our constitutional protections in the United States, the Legacy Bill denies victims and families access to the courts, due process of law, and justice itself.

The Legacy Bill does not further justice for the victims and families, it ends it. All five political parties in Northern Ireland reject the Bill, including the leadership of Sinn Féin and the DUP who are, in most circumstances, in opposition to each other. The provisions in the Legacy Bill clearly merit a reevaluation. If the Bill passes the House of Lords, and attains Royal assent, it will become a Legacy Bill of injustice.

Michael C. Mentel is an Appellate Judge on the Ohio Court of Appeals Tenth District. Prior to taking the bench, he was a partner with Taft Stettinius & Hollister. He is admitted to practice in Ohio, the United States District Courts, northern and southern divisions, the United States Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court of the United States.