A case can be made for the years 1879, 1880 and 1881 being more consequential than any others since in the making of modern Ireland.

In 1879, the Irish National Land League was founded against the backdrop of an economic downturn that led to famine conditions in some parts of the country.

“The drop in European agricultural prices in the years 1877-79 – partly the result of American competition – greatly impacted rural Ireland and hit farmers at the same time as a series of cold winters and wet summers,” writes Niall Whelehan in “Changing Land: Diaspora Activism and the Irish Land War.”

By 1880, Land League co-founder Michael Davitt was claiming that the movement had over 200,000 members and “virtually rule[d] the country.”

And 1881 saw the Land Act, which was radical, says Whelehan, in that it “introduced ambivalence into ideas of land ownership in Ireland by increasing the level of state interference in property rights and limiting landlords’ ability to decide rents and changes in tenantry.”

He adds, “The Prime Minister, William Gladstone, succeeded in selling the legislation in Parliament through promises that it was ‘something peculiarly “Irish” and unexportable to Britain.’”

“‘Changing Land’ is about how people, in Ireland and in the Irish diaspora, advanced new and radical ideas of social reform during a transformative moment in Irish history known as the ‘Land War’ of the 1880s,” Whelehan told the Echo. “This was also the period with the highest numbers of Irish emigrants in the history of the diaspora.”

Five million people lived in Ireland and there were three million Irish-born people abroad, of which about 60 percent were in the U.S.

“The book traces the lives of activists who were present in Ireland, the USA, Argentina, Scotland and England and the networks of people and ideas that connected them,” the author said. “Their campaigns caught the attention of radicals around the world as they spoke about universal issues of rent, housing, democratic rights, landlordism. They combined the cause of anti-landlordism in Ireland with labour, feminist and humanitarian causes in their new homes”.

“The Land League and the Ladies’ Land League consciously sought emigrant support and appealed to the imagined geography of an ‘Irish world,’” Whelehan writes in “Changing Land,” which is part of the Glucksman Irish Diaspora Series.

Indeed, they regarded such support as vital; leading activist Anna Parnell once declared the campaign would collapse “without external help.”

Whelehan’s aim, he says in the book’s introduction, is “to uncover new layers of radical circuitry between Ireland and disparate international locations. Looking beyond the leadership figures brings unfamiliar voices to the surface, women and men who have been on the margins of – or entirely missing from – existing accounts. Until relatively recently, their stories could not be easily traced, but the expansion of digital archival databases helps make their recovery increasingly possible.”

The author has written four biographical chapters – on Peter O’Leary, Marguerite Moore, John Creaghe and Thomas Ainge Devyr – as well as another that is a study of the Ladies’ Land League in Dundee, Scotland.

O’Leary was a “London-based emigrant who regularly toured Ireland and the United States and sought to strengthen ties between the Irish in Britain and Irish America”; Moore was a “traveling agitator for the Ladies’ Land League who toured Ireland, Scotland and England and helped integrate the organization across the Irish sea,” before emigrating to America; medical doctor Creaghe, influenced by American radical author Henry George and the Land League, wanted to launch a campaign against Argentine landlords, some of whom were of Irish Catholic heritage; Devyr was a veteran land reformer “whose long career linked the Irish land question, English Chartism, and American agrarian radicalism.”

All four supported nationalization as the answer to the land question. They were in a minority, with the supporters of peasant proprietorship being in control of the movement; but it was a substantial minority with key supporters like Davitt, the most famous land activist, and Patrick Ford, the editor of the New York-based Irish World, which sent Henry George as a correspondent to Ireland to report on the land struggle for a year.

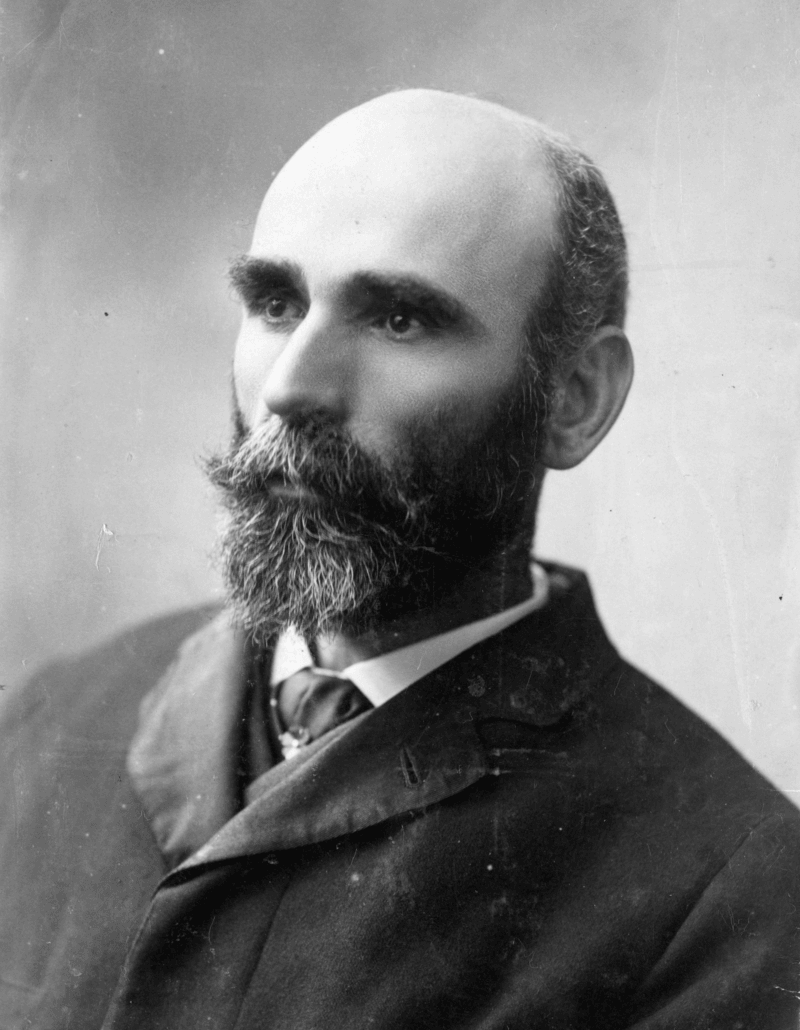

Michael Davitt.

Supporters of both the moderate position of peasant proprietorship and the radical nationalization idea were united in believing that only those who worked the land had a right to it. Davitt said that “rents for land are an immoral tax upon the industries of the people.” Others internationally spoke in similar terms. Whelehan says that the Scottish land reformer John Murdoch lectured in America on the “immorality of the existing land system” and he quotes Newcastle trade unionist John Bryson saying lands worked by tenant farmers “were morally their own, if not legally.”

Ireland’s 1880s Land War was designed not just to stop evictions and to lower rents, but also had the more ambitious goal of overthrowing landlordism altogether.

“The story of the Land War reveals much about the wider histories of radicalism,” writes Whelehan, a lecturer at the University of Strathclyde. “It was part of a broader ideological challenge to property rights and the inequalities they produced that sought to fundamentally change how land was thought about and used.”

Later, the author adds, “The Land War resonated outward and influenced groups including, for example, the Social Democratic Federation in Britain [the country’s first socialist party], the Knights of Labor [in the U.S.], radical Ukrainian nationalists, and European anarchists, who sought to emulate some of the Land League’s tactics.”

The Land War was violent but the number of fatalities was low. It, in part, grew out a “new departure” involving an alliance between the constitutional and physical-force strands of nationalism, which the New York-based Fenian John Devoy and the former Irish Republican Brotherhood organizer Davitt helped broker.

The Irish Parliamentary Party, under the leadership of Davitt’s co-founder of the Land League Charles Stewart Parnell, was to emerge out of the tumult as a major force in the 1880s.

For Whelehan’s subjects, “nationalism was one part of a worldview that incorporated multifaceted dimensions, including support for radical as well as liberal causes.”

And yet, despite their liberalism and radicalism (Dr. Creaghe was later a leading Argentine anarchist), they showed little enthusiasm when the cause involved supporting racial minorities.

With the shift in priorities in the 1880s, the Land League became the National League, a move later described by Davitt as a “counter revolution”; he regretted that radical voices were marginalized in the interests of unity, and that while there were “real gains” made, the poorest farmers and laborers were not beneficiaries.

“An outstanding work, meticulously researched, lucidly written, and conceptually sophisticated. ‘Changing Land’ promises to be one of the most exciting books published on Irish history this year," Thomas Bartlett, Professor Emeritus, University of Aberdeen, said of the book. "Whelehan is an outstanding scholar and this volume will consolidate his reputation as among the leading historians of Ireland."

"’Changing Land' is a fascinating study of class, gender, social and political reform, and the diaspora during the Land War in 19-century Ireland," said Bernadette Whelan, Professor Emeritus, University of Limerick. "It argues convincingly that the land war was part of a wider ideological moment in world history and that social activism should be accorded attention equal to the political perspective, in the nationalist narrative."

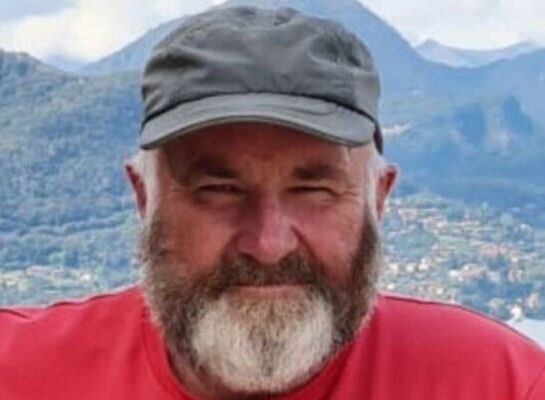

Niall Whelehan

Place of birth: Ireland

Published works: “The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World”; “Changing Land: Diaspora Activism and the Irish Land War.”

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

I am not sure there are ideal conditions. I have two young children and completed “Changing Land” during Covid lockdowns so it was really a matter of grabbing whatever periods of silence that were available to write. My only rules are to turn off the wifi and hide my phone in order to minimise distractions and get into the flow of it.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Persevere. I find writing books to be exhausting and it always takes longer than planned. Doggedness is necessary.

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

The books that immediately come to mind are ones that I have read recently. Anna Burns’s “Milkman” is a novel about the Troubles and is a book for the ages that I would recommend everyone read. Claire Keegan’s “Small Things Like These” is a novel about a small Irish town in the 1980s and the dark history of Ireland’s religious institutions. Finally, I’ve just read Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward “Lives, Beautiful Experiments,” a fascinating history book that takes a creative approach to explore Black women’s lives in turn-of-the-20th century New York and Philadelphia.

What book are you currently reading?

Fearghus Roulston’s “Belfast Punk and the Troubles: An Oral History.” A fascinating and alternative history of the Troubles through a focus on music culture.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

I think many historians of Irish migration and Irish America are somewhat in awe of Kerby Miller’s classic study “Emigrants and Exiles.” It was first published some forty years ago but remains a powerful read with a remarkable depth of archival research.

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

Flann O’Brien, a great author and a great sense of humor.

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

The Bog of Allen in County Westmeath.