“I am the President of the United States, not you. When I say I want to go to Ireland, it means that I’m going to Ireland. Make the arrangements.” With that command to his long-time right-hand man, Dave Powers, sixty years ago President John Fitzgerald Kennedy overrode objections to travel to his ancestral homeland.

His visit - the first by a serving President - has an enduring legacy. JFK’s lineage traced to his paternal great-grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, a cooper from New Ross, County Wexford. Fifteen percent of New Ross residents died in the Famine, which started in 1845.

He took passage on a “coffin ship” for Liverpool then to Boston, taking with him what he could carry. All the new Irish in Boston were required to live in a segregated section of the city. He married Bridget Murphy, also from Wexford.

On JFK’s maternal side, in 1914 his father, Joseph Kennedy, married Rose Fitzgerald, daughter of one of Boston’s most prominent Irish families, originally from Limerick. As one of nine children, JFK was raised in a family of high expectations.

Anti-Irish and anti-Catholic prejudice suffered by ancestors at the Boston docks and continuing to elite schools was to be overcome. His father, chairman of the SEC and later ambassador to the United Kingdom, set a challenging family standard.

During his political climb, JFK made three trips to Ireland. In 1945, as a 28-year-old cub reporter for the Hearst newspapers, he used his family’s reputation to arrange a visit to Dublin, where he interviewed the former revolutionary and then Taoiseach Éamon de Valera, and later wrote favorably about his experience.

As a newly elected Congressman from a heavily Irish district, Kennedy returned in 1947 for an opulent three-week stay with his sister, Kathleen (the widow of the Duke of Devonshire), at Lismore Castle, County Waterford. While there, he journeyed to Dunganstown to meet father’s-side third cousins who lived in a thatched-roof cottage with an outdoor toilet. Despite the contrast in living conditions, JFK left with a feeling of sentiment and nostalgia.

While touring Europe in 1955, Senator Kennedy and his wife, Jacqueline Bouvier, stopped in Ireland for a brief meet-and-greet with Irish leaders designed to boost his image with Irish-American voters back home.

By 1960, Kennedy’s ascent and family wealth offered a presidential campaign opportunity. Kennedy snatched it, candidly addressing voter concerns that he was too young, Irish and Catholic, to hold office.

He defeated Richard Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections in American history. Meanwhile, Ireland faced formidable challenges. High unemployment and constant emigration had reduced the population to under three million. Many homes lacked running water and electricity. Struggling farmers sought urban employment in recently-opened industrial plants.

The country ranked as an afterthought in European affairs and American foreign policy. It stood firmly in the shadow of the British-American “Special Relationship” which had been enhanced by their partnership in defeating Axis powers in World War II - a conflict in which Ireland had remained neutral. Taoiseach Sean Lemass, however, a proponent of economic reform and improvement of Ireland’s lowly status, viewed JFK’s prominence as an opening to establish a productive Irish-American connection.

His ambassador to the U.S., Thomas Kiernan, led the charge, weaving statecraft and personal bonhomie with the young president to encourage an Irish visit. Finally, in March 1963, JFK agreed. But to justify a diplomatic encounter with such a strategically unimportant country, it would have to fit into a broader, essential, European trip.

Summer 1963 offered the moment, politically and personally, for Kennedy to depart. In 1962, he had deterred nuclear war with Russia over missiles it was installing in Cuba. Still, Cold War tensions remained hot, and assorted internal political issues were bedeviling Germany, Britain, and Italy.

With an 82% approval rating, Kennedy had political capital to spend. Thus, a tour of the three allies was arranged. Ireland was added, at his insistence. It was a choice widely viewed with derision. An offer to visit Northern Ireland was declined due to a tight schedule, but more likely to avoid provoking Anglo-Irish relations.

Kennedy arrived on June 23 in West Germany, where he was greeted enthusiastically. On June 26, he flew to Berlin: the Cold War demarcation where the city, country, and world was divided literally and symbolically by the Berlin Wall. Emotionally overcome after looking at and over the wall, he improvised an impassioned “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech of support to a 120,000-strong crowd. It remains one of the most famous foreign policy speeches in American history.

Hours later, JFK flew to Ireland for a four-day stay, joined by sisters Eunice Kennedy Shriver and Jean Kennedy Smith and an “Irish Mafia” contingent of advisors of Irish-American heritage. He was greeted at Dublin’s airport by President de Valera who gave a welcoming address in Gaelic and English and stayed by his side at some upcoming ceremonial events.

In two full days and two partial ones, months of advance planning guided JFK on a whirlwind tour: Dublin, New Ross and nearby Dunganstown to revisit relatives, Wexford Harbor; a garden party at de Valera’s residence; a stop at Iveagh House for a high-level dinner with Lemass and politicos. Additional visits to Cork City, Arbour Hill and Leinster House for a televised address to the Dáil, Dublin Castle to receive honorary degrees from National University and Trinity College. And there was Galway, Limerick and Shannon Airport in County Clare for departure. There was no time for naps.

The tour became a hectic, mutual love affair. Kennedy developed a rapport with Lemass, de Valera, and other leaders, discussing Cold War affairs and Ireland’s current status, both domestically and internationally.

And at every location he was treated like a celebrity, receiving countless introductions, handshakes, photo requests, and surging masses clamoring for a glimpse or touch of the returning handsome son who had made the grade. Even Ireland’s business and high society leaders fell to JFK’s youthful charisma, sloppily mobbing him at the garden party in a “demonstration of uncouth bad manners, ignorance, and bad breeding,” according to the Sligo Champion.

Kennedy frequently embraced his heritage. He quoted and name-checked numerous Irish and Irish-American historical figures, presented a Civil War battle flag from the Irish 69th regiment, and became the first head of state to attend the annual Arbour Hill ceremony honoring the leaders of the 1916 Rising.

Although he deferred to the Special Relationship by refraining from any overt statement criticizing Partition, his attendance at Arbour Hill and comments elsewhere hinted at support of reunification. The most “modern” stopover took place in Limerick, which was not part of the trip’s original itinerary. Frances Condell - Limerick’s first woman mayor, and a Protestant in a city 98% Catholic - refused to accept the snub.

Armed with the Fitzgerald ancestry connection and her feisty, persistent nature, she successfully cajoled Limerick’s inclusion at the last minute. When Kennedy arrived on June 29, her 47th birthday, Condell gave a humorous, lyrical introduction that covered emigration, Fitzgerald relatives in attendance, and Jacqueline Kennedy. More importantly, she alluded to five newly-opened industrial businesses nearby, urging Kennedy to send American commerce to the region.

She sought the future and was the future: the only woman to give a speech during Kennedy’s visit, at a time when women political leaders were practically non-existent—in her country and ours. Kennedy left Ireland emotionally moved, recounting his time with staff and family while enthusiastically re-watching films of his stay - and not the famous Berlin speech.

Suddenly, five months later, just 46 years old, he was assassinated in Dallas, a tragedy that hit Irish people especially hard. But the JFK-Ireland legacy lives on. A flame from his Arlington gravesite was used to light the Emigrant Flame in New Ross, which eternally commemorates those who fled hardship.

His brother, Ted, and sister, Jean, as Senator and Ambassador to Ireland, respectively, played key roles leading to the Good Friday Agreement, bringing peace to Northern Ireland. His great-nephew, U.S. Northern Ireland Special Envoy Joseph Kennedy III, visited the North in April to facilitate its economic and political progress.

And, simultaneously, President Biden, with roots to ancestors from Counties Mayo and Louth, travelled briefly to Northern Ireland, then on for a three-day stay in the Republic for a mixture of politics, diplomacy, and homecoming. Wearing his Irishness on his sleeve, he repeated the proverb he learned from his grandfather: “Your feet will bring you to where your heart is.”

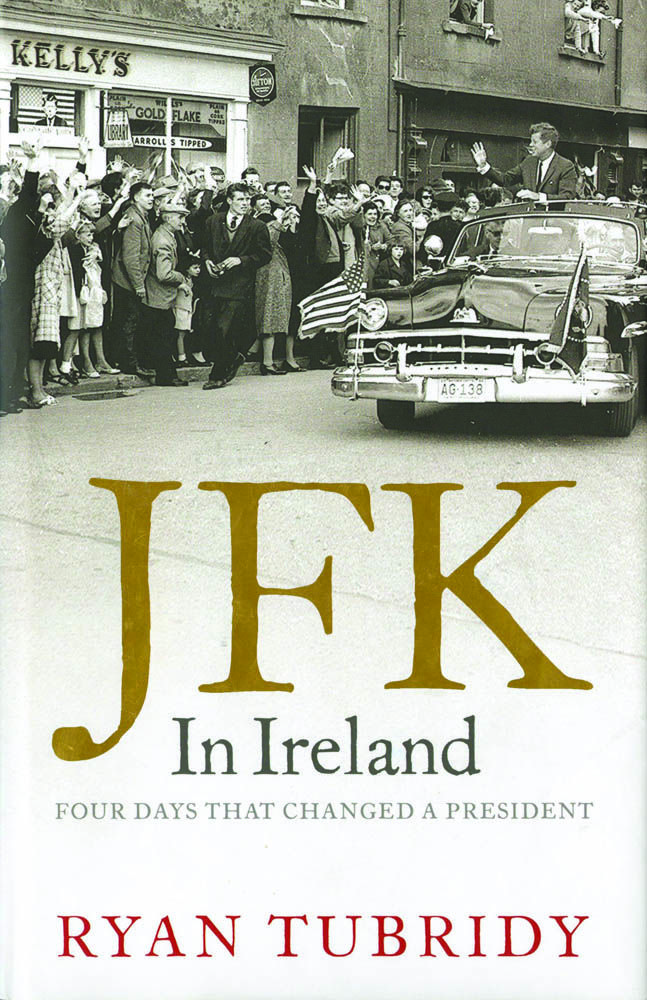

Prior to Biden’s trip, CNN noted that his reading list included Ryan Tubridy’s "JFK in Ireland," a fascinating book covering the diplomatic seed planted 60 years ago. Today, American foreign direct investment in Ireland totals $390 billion, employing over 340,000 people in roughly 900 U.S. subsidiaries. And the U.S. is the largest foreign investor in Northern Ireland. The seed has branched in ways Lemass and Condell could never have fully imagined.

James J. Brosnahan and Dan VanDeMortel have published Northern Ireland Presidential and Congressional scorecards, frequently visited Ireland and Northern Ireland, and written about Irish political and legal affairs. Brosnahan’s to-be-published 2023 memoir will cover, in part, his investigation of the murders of lawyers Rosemary Nelson and Patrick Finucane.