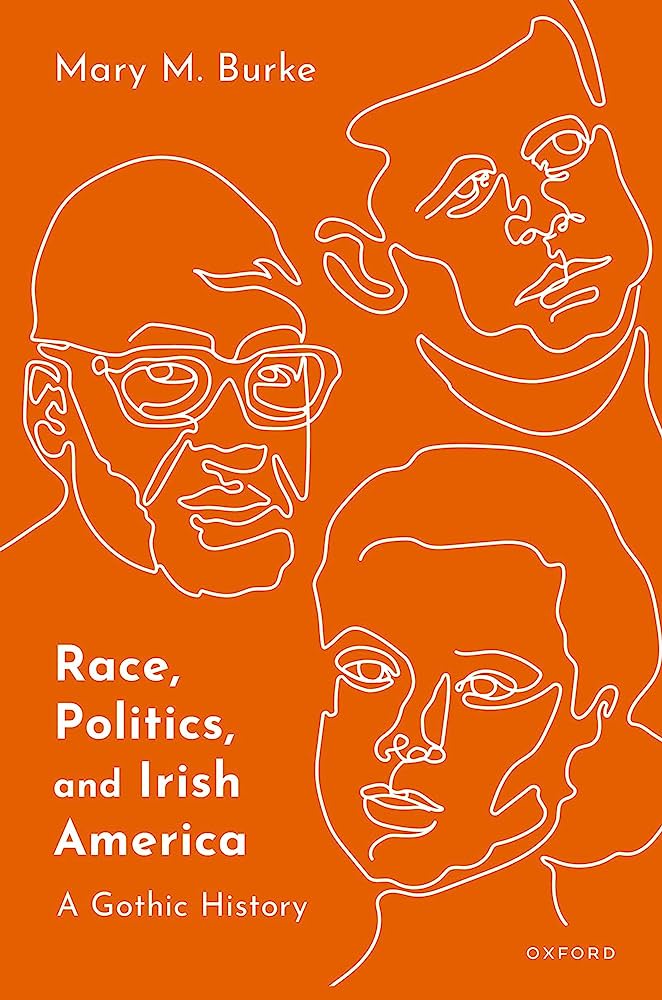

University of Connecticut Professor Mary M. Burke has written a book that the field of Irish Studies in the United States will find hard to ignore or dismiss.

“Race, Politics and Irish-America: A Gothic History,” she told us, “uses the words and lives of Black and white writers, politicians, and performers of Irish connection to examine centuries of Irish presence in the Americas.”

Her work is a cultural history that looks at racial and social status in America, in part by taking in the stories of the forcibly transported 17th-century Irish, the Scots-Irish of the 18th century and on up through those who came in the Famine and post-Famine waves of Catholic immigration.

The study considers figures as varied as President Andrew Jackson, the quintessential Scots-Irishman, “Gone with the Wind” author Margaret Mitchell, who was of Irish Catholic background on her mother's side, and the present-day Caribbean-Irish singer and actress Rihanna.

The author compares the rather contrasting ways in which F. Scott Fitzgerald and Eugene O’Neill processed their Irish Catholic heritage, and looks at how Edgar Allan Poe and Henry James dealt with their Ulster roots.

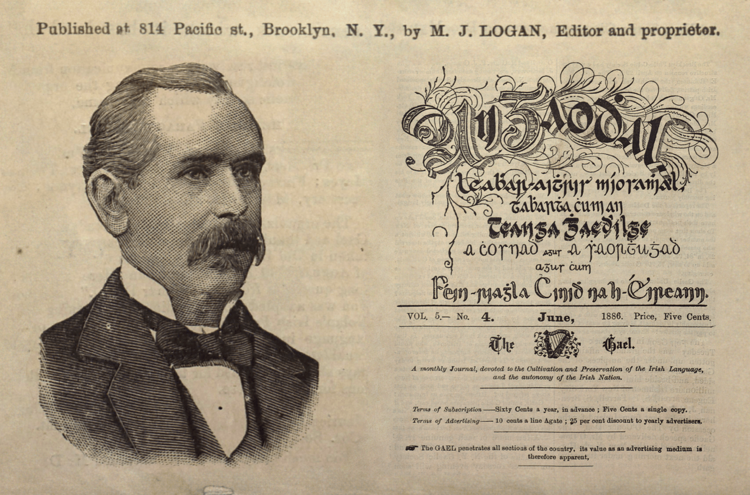

Burke examines, too, the implications of the way Irish-Americans viewed differently John Mitchel, a founding father of militant Irish nationalism and a defender of slavery, and his grandson John Purroy Mitchel, a New York City mayor.

Burke writes: “M.H. Abrams’s classic study [‘The Mirror and the Lamp’] suggested that mirrors have long been regarded as symbols of art conceived as a faithful mimetic representation of external reality; writing of ‘Dubliners,’ James Joyce described his stories about the Irish capital city as a ‘nicely polished looking-glass.’ When it comes to reading Irishness in American literature, however, more useful than Joyce’s flat mirror is the convex mirror of the sort used on the side of cars. This gives a wider field of view and requires that one bears in mind what might be creeping up behind during forward motion. Thus, that which is at one’s back is simultaneously present at all times and is ignored at the driver’s peril. When the literature of Irish America is considered as a convex mirror whose distortion nevertheless allows for a stereoscopic of history, then both realistic and non-realistic texts emerge as reflections and of unfinished Irish and Irish-American pasts that continue to inform.”

Not all the fiction discussed is Gothic literature, but “cultural expressions in that mode repeatedly emerge in this volume because history is undead in Irish-American narrative. That unfinished Irish past replays within American contexts of race, slavery, settler-colonialism and ethnic hierarchies.”

At one point, Burke considers three novels that “depict planters of broadly Irish connection in the antebellum and post-Civil War South”: Mitchell’s Gerald O’Hara in “Gone with the Wind,” William Faulkner’s Thomas Sutpen in “Absalom, Absalom!” and Frank Yerby’s Stephen Fox, a Dubliner, in “The Foxes of Harrow.”

The author comments, “The works differ in register: Faulkner writes difficult Gothic modernism that simultaneously mourns and condemns the ‘Old South’; while the more accessible historical romances of Yerby and Mitchell portray slavery in diametrically opposed ways. Nevertheless, all three fictions center on penniless and initially ‘off-white’ protagonists of pre-Famine Irish or pan-Gaelic association who transform themselves into white exploitative landowner class to whom they themselves had once been subject.”

“Absalom, Absalom!” and “Gone with the Wind” were both published in 1936; for Burke, though, the former strips away “Mitchell’s Southern mythology to reveal the consequences down through the generations of the original sin of forced labor in the Americas. Faulkner’s ‘poor white’ Sutpen, who secures status by becoming a plantation master, will be read as a critique of the very earliest attempt by those of British and Irish origin in the Americas to become white. Mitchell, by contrast, unapologetically claims whiteness for the Catholic Irish by installing the O’Haras as equals of a neighboring Scots-Irish-owned plantation.”

Yerby wrote about a variety of backdrops and eras and by 1954 was estimated to be America’s highest-paid novelist; however, the 1946-published “The Foxes of Harwood” was considered to be his breakthrough book. He was an African-American with a Scots-Irish background on his mother’s side. That latter part of heritage has been largely erased, Burke says, even though he claimed to an interviewer a few years before his 1991 death that he had more Irish blood than Black. (He was during his youth attacked by a police officer for walking on the street with a white woman – she was, in fact, his sister.)

Yerby is depicted on the book’s front cover alongside those of Grace Kelly and President John F. Kennedy, among the most famous Irish Americans of them all. Burke details the careers of the actress’s father, John B. Kelly, a successful Philadelphia businessman and athlete, as well as two prominent uncles, Walter Kelly, a vaudevillian who traded in racist stereotypes, and closeted gay playwright George Kelly (the author says the future Princess Grace herself “actively defended sexual and racial minorities when this was neither profitable nor popular in most mainstream white-dominated spheres” and championed Uncle George’s work to an “indifferent Kelly clan”).

Grace Kelly’s closeness to and good working relationship with the East London-born film director Alfred Hitchcock were facilitated, in Burke’s view, by their shared Irish immigrant heritage, their Catholic schools background and the fact they were both “quite culturally Catholic in outlook.”

Burke told the Echo, “I argue in ‘Race, Politics, and Irish-America’ that Kelly’s globally broadcast and unapologetically Catholic royal wedding ceremony [in 1956], which was watched by 30 million people, altered the trajectory of her ethnic community.”

Burke sees that event as helping to pave the way for the brief years of Camelot at the White House. The Kennedy story has been thoroughly Gothicized, in her view, by the family’s admirers and detractors alike. For liberals and progressives, Jack Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy were victims of dark forces opposed to their enlightened world-view and coalition-building across racial lines. Meantime, the “Kennedy Gothic of conservatives and Irish-American voters abandoning hereditary Democratic Party allegiance portrayed ‘America’s royals’ as being enmeshed with the moral decay at the heart of power, a central theme of Gothic since its inception.”

Professor Burke’s earlier book with Oxford University Press was a cultural history of the indigenous Irish Traveller minority. Her collaboration with Tramp Press on a new edition of “The Horse of Selene,” Traveller novelist Juanita Casey’s lost classic, was launched at NYU’s Glucksman Ireland House in April.

Burke has served on Fulbright’s Screening Committee for Ireland and is a graduate of Trinity College Dublin and Queen's University Belfast. She first came to the U.S. when she was an NEH Irish Studies Fellow at the University of Notre Dame after finishing a PhD in Queen’s University Belfast.

Mary M. Burke.

What book are you currently reading?

I am currently rereading Dublin novelist Anne Enright’s 2020 book, “Actress.” The novel is loosely based on Irish-American legend Maureen O’Hara, a movie star who also features in my cultural history. I had the pleasure of doing an event with Enright on the reality and fantasy of the Hollywood Irish actress at Sacred Heart University on March 31, so I am rereading “Actress” with fresh appreciation for her insights.

Name a book that you were pleasantly surprised by.

Maureen Dezell’s “Irish America: Coming into Clover” is a wonderfully sharp and unsentimental portrait of Irish America. An insightful, accessible history that challenges every cliché, it became a model for the tone I aimed to achieve in my new book.

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

The Westport and Newport areas of Mayo, which have the ideal combination of good food, great scenery, and deep history, from Kelly’s Café to many bookshops and on to Croagh Patrick, a fiercely barren mountain and pilgrimage site associated with Ireland’s patron saint. Of personal interest to me is that the Newport hinterland is the ancestral home of Grace Kelly, the Irish American actress who became Princess of Monaco in 1956. In 2017, when I was researching my current book, I enjoyed a magical road trip with my mother (an obsessive Kelly fan) when we went in search of the Kelly cottage in Drimurla, near Newport, which is not signposted. Princess Grace became a central subject in my book as a result of this trip.

You're Irish if...

I don’t have to tell you that a famous actress whose surname was “Kelly” was Irish American!