The story of Sean Quinn is a story about the Border and its people. I was born in Enniskillen and, living in the shadow of the industrial complex the quarryman built between Derrylin and Ballyconnell, hearing all the stories of what this incredible entrepreneur had achieved despite all the challenges.

Because in building his business, Sean Quinn not only defied logic, he had taken on monopolies on both sides of the Border as well as the government and institutions in Dublin and Belfast that had little interest in creating jobs and wealth on either side of the Border.

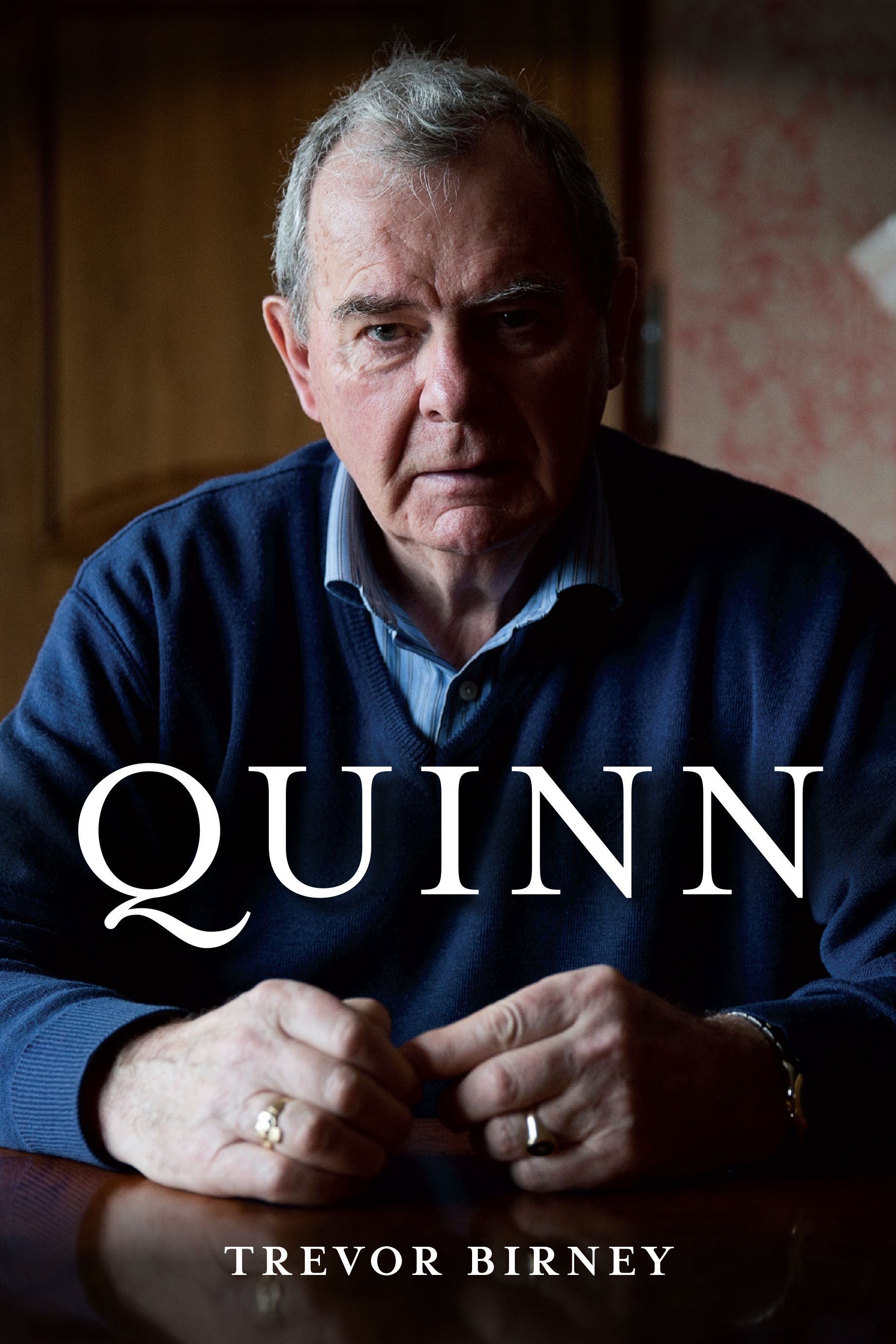

I first approached Sean Quinn’s management team about a documentary over ten years ago. At the time, they were fighting for their very survival so it was no real surprise they passed on my pitch. During his rise to become the richest man in Ireland, Sean had taken the decision to stay away from the cameras, to do very little media, which only added to the myth of the man who was building an empire on the Border.

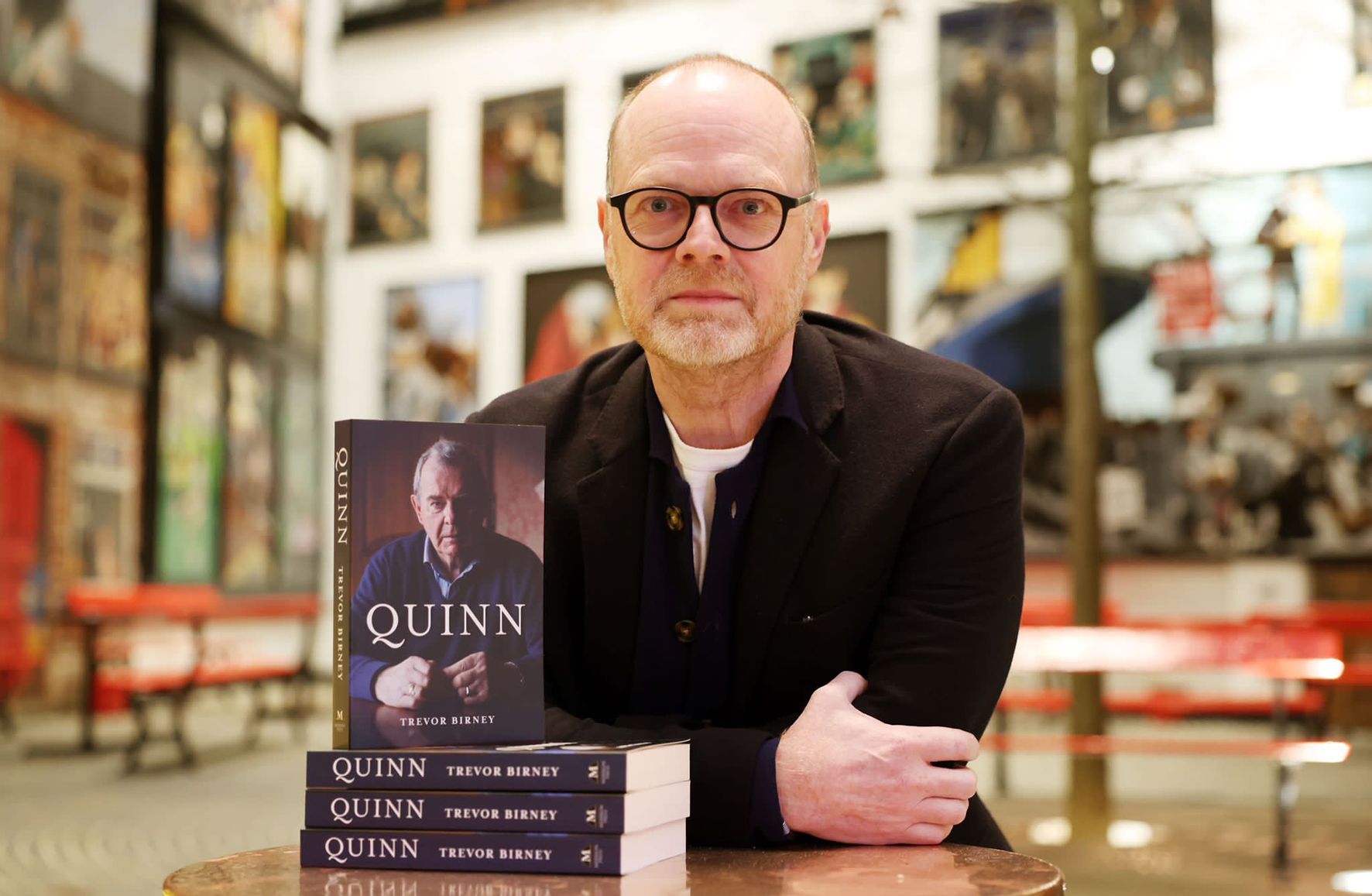

Then, four years ago, a new opportunity opened up to meet with Sean at his home. Over the course of a number of meetings he agreed to take part in a documentary project. Last December, RTE broadcast “Quinn Country” over three nights to huge audiences. The quarryman’s story captivated the country. The book “Quinn” was published the same week and went straight to the top of the non-fiction charts, becoming a Christmas number one.

The documentary series told the story of Sean Quinn from his humble beginnings to his downfall, but it was the comments of a former Fine Gael leader, Alan Dukes, that caused the most reaction. In the third episode, Dukes, who had been tasked with reaching an agreement with Sean Quinn on how to repay the €2.8 billion he owed the Irish taxpayer, said: “Border people have it in their blood. They are living in communities that have a long history of violence of different kinds. They will more easily turn to it than anybody else will.

Trevor Birney.

I remember interviewing Alan Dukes well. The only thing that shocked me was the fact that he was prepared to make the comments on camera. No one who comes from the Border area is under any illusion of how we are viewed in Dublin. At least Dukes had the honesty to say it, although he had to later retract and apologize, under pressure from Fine Gael.

It’s almost 15-years since the Celtic Tiger bubble burst, but from the reaction to the series and the book, it’s very clear that Irish audiences are still fascinated by the events that led to Sean Quinn becoming the single biggest loser of the global economic collapse.

It’s also clear that there is huge sympathy for Quinn, with many people across the island of Ireland believing he should have been given a chance to repay his debts and get back on his feet. The quarryman believes that if he had been given the chance, he’d have dug himself out of Trouble.

Sean Quinn started out in business at a time when the only significant building works on the Border were being undertaken by the British Army. Checkpoints were appearing on the main arterial routes linking the Border counties while dozens of other roads were closed. Soldiers manned road blocks, causing huge disruption to everyday life.

But despite the militarization, Quinn showed great determination to realize his vision. Having started digging down into the 26 acres he inherited from his father in December 1967, he bought his first lorry, then another, and by 1973 he had a fleet of lorries drawing shale from the farm on the Mountain Road between Derrylin and Ballyconnell. The British army checkpoints meant his lorries had to take a circuitous route to cross the Border and at one point he punched a soldier who held him up on the way to a wake.

Slowly, Quinn began to singlehandedly change the fortunes of the area. With little or no employment opportunities, the area had been plagued by emigration of its young people for generations. By the late-80s, Quinn was offering good jobs and decent salaries. More, he was offering careers. A generation had a realistic option to build a home, build a life on the Border. The Irish government had done nothing to keep them at home, but Sean Quinn changed that. The lights on Doon Mountain above Quinn’s quarry had been dimmed by emigration. Now, according to one local historian, Quinn was putting the lights back on the mountain.

He built a cement factory, despite the efforts of Dublin cronies linked to Charles Haughey who wanted to protect their monopoly on cement sales, and Unionists wanting to ensure the Border man didn’t receive a penny in British government support.

Then a roof tile company and a glass plant and a plastics factory. When Quinn was shocked by the cost of insuring the company’s fleet of lorries, he responded by opening his own insurance company. At one point it appeared that Quinn Direct was insuring every 17-year-old in the country.

But despite the militarization, Quinn showed great determination to realize his vision. Having started digging down into the 26 acres he inherited from his father in December 1967, he bought his first lorry, then another, and by 1973 he had a fleet of lorries drawing shale from the farm on the Mountain Road between Derrylin and Ballyconnell. The British army checkpoints meant his lorries had to take a circuitous route to cross the Border and at one point he punched a soldier who held him up on the way to a wake.

Quinn was challenging the status quo, upsetting the boardrooms in Dublin, Belfast and beyond. He was a threat and his single minded attitude meant he couldn’t be bought. He didn’t want to be part of the Dublin set. He’d no interest in being in the tent at the Galway races.

Some of his former colleagues believe Sean Quinn’s head was turned around 2004. He had bought a helicopter but now wanted a jet. He began to invest heavily in what were known as Contracts for Difference, a financial instrument that allows you to effectively buy shares in a company without the company knowing you have bought them.

The quarryman built up a 28% share in Anglo-Irish Bank, the “best little bank in the world” at the time. He poured over the annual reports produced by the bank’s chairman and chief executives. He believed every word, not knowing they were bullshit. Anglo Irish Bank was little more than a Ponzi scheme and when the 2008 economic collapse came, it folded. Brian Cowan’s government stepped in with the banking guarantee and overnight Sean Quinn owed the Irish taxpayer €2.8 billion.

The story of his downfall is well known. Quinn ended up bankrupt and spent nine weeks in Mountjoy Prison. The people of the Border area came out in their thousands to support him while the Dublin media sneered at their loyalty. Violence returned to the Border with a campaign designed to ensure that none of the businesses could be sold off until Quinn could make a second coming. He did get the chance in 2014, but it quickly became apparent that the world had changed and he was no longer the man in charge. He fell out with his executive team and after leaving the company, they became the targets of a second phase of attacks. In September, 2017, his former right hand man, Kevin Lunney was bundled into the boot. of a car and driven across the Border where he came under a sustained and vicious attack. Quinn said he was being blamed but denied any responsibility. But he knew that locals were no longer looking at him the same way.

He retreated behind the high gates of his 15,000 square foot mansion, where we first met. Over the years we worked on the documentary series and the book, I found Sean Quinn to be a stubborn man but someone who had retained a good sense of humor despite all he had come through. He showed flashes of anger and frustration at how life had turned out for him. He wanted the world to know his truth.

Since I married my wife in New York City Hall 23-years ago this week, I’ve been lucky to make some very good friends in the city that’s become a second home. A Tyrone man, Owen Rodgers, supported my colleague Barry McCaffrey and I after we were arrested for breaching British National Security by revealing in our documentary, "No Stone Unturned," a secret document on the collusion between the RUC and Loyalist killers in the 1994 attack on a small bar in Loughinisland in which six men died.

Owen had watched the Quinn documentary and it was his suggestion to launch the book in New York. Thanks to Owen, I hope readers will get to know Sean Quinn a little better. He’s the man who put the lights back on the mountain.

"Quinn" is published by Merrion Press, www.merrionpress.ie. The book is also available on amazon and the Barnes & Noble website.