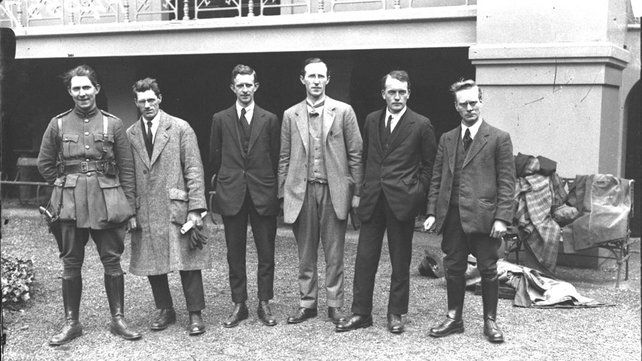

Picture caption: Military representatives, from left, Seán Mac Eoin (pro-Treaty), Seán Moylan (anti), Eoin O’Duffy (pro), Liam Lynch (anti), Gearóid O’Sullivan (pro) and Liam Mellows (anti) met at the Mansion House, Dublin, in May 1922 in an attempt to find common ground.

When, 100 years ago – on June 21, 1922 – Seán Mac Eoin married Alice Cooney in Longford a few high-profile invited guests showed up. Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, the most notable of them, posed with the 28-year-old groom and his bride for the photographers and newsreel cameramen. All of the assembled appeared in high spirits, despite the troubling backdrop.

The beginning of the Civil War is dated to the shelling of the Four Courts exactly a week later, on June 28. But there had been killings before that. In April, a close aide to Major General Mac Eoin, General George Adamson – a local comrade in the War of Independence -- had been shot dead by the anti-Treaty IRA.

Members of Royal Irish Constabulary were still being targeted at high rates in early 1922, something that would have troubled Collins, who’d once hoped that that body would form the basis of the new police force in an independent Ireland; through emissaries, he’d also been encouraging Catholic officers to stay on in the rebranded RUC north of the border.

A year before his wedding, Mac Eoin had been under sentence of death in Dublin. There were appeals for clemency for the “Blacksmith of Ballinalee,” with testimony from the enemy camp citing his chivalry in battle and toward those his Flying Column had captured.

Collins sent a team comprised of some of his most trusted men to spring Mac Eoin from Mountjoy Prison; although they breached prison security wearing British army uniforms, they couldn’t locate the condemned man and had to retreat. Collins saved him ultimately by making his release a condition of peace terms in the Truce announced for July 11, 1921.

A few months later, Mac Eoin seconded Griffith’s Dáil resolution backing the Treaty. As the country hurtled towards civil war, Mac Eoin participated in political and military efforts to stave off conflict. In the latter category was a May meeting at the Mansion House between Mac Eoin, Eoin O’Duffy and Gearóid O’Sullivan for the new National Army and Seán Moylan, Liam Lynch and Liam Mellows for the anti-Treaty IRA.

O’Duffy and Lynch in the center of pictures and newsreel footage [as shown above] were the senior figures for the respective teams. Both, though, had only graduated from cultural nationalism to the politics of “advanced” nationalism in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. The other four had a long association with the revolutionary Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Mac Eoin, for one, was now following the majority line within the IRB under Collins’s leadership, which was: the time is right to move from revolution to democracy.

He said in his speech seconding Griffith, “I take this course because I know I am doing it in the interests of my country, which I love. To me symbols, recognitions, shadows, have very little meaning. What I want, what the people of Ireland want, is not shadows but substances, and I hold that this Treaty between the two nations gives us not shadows but real substances."

The tone of Mellows’s contribution could hardly have been more different to that of Mac Eoin’s. He said, “We do not seek to make this country a materially great country at the expense of its honor in any way whatsoever. We would rather have this country poor and indigent, we would rather have the people of Ireland eking out a poor existence on the soil; as long as they possessed their souls, their minds, and their honor. This fight has been for something more than the fleshpots of Empire.”

Lynch was considered a relative moderate, as he’d suggested the Free State would be acceptable if it had a republican constitution. He opposed the occupation of the Four Courts by his more militant comrades such as Mellows.

But the killing of Collins in an ambush on Aug. 22 (10 days after Griffith’s death from natural causes) and the passing of draconian emergency powers by his successors hardened feelings on both sides. Anyone captured with guns or ammunition could be tried before a military court, which is what happened to notable opponent of the Treaty Erskine Childers, found with a gun given to him by Collins. He was executed on Nov. 24, becoming the third person who’d voted against the Treaty in the Dáil to die violently in the new war (Cathal Brugha and one-time Collins friend Harry Boland were both killed during the summer).

Lynch, as chief of staff of the Republican forces, declared that all who’d voted for emergency powers in the Dáil and the Seanad were to be targeted.

On Dec. 7, IRA members shot dead the pro-Treaty Seán Hales TD and seriously wounded Pádraic Ó Máille TD as part of that stated policy.

In what was in some ways the most shocking government action in the entire 10-month war, the cabinet ordered the executions of four prominent Republicans, who’d been in custody since the fall of the Four Courts garrison during the summer, thus before any of the repressive laws had been passed.

Mellows, Joseph McKelvey, Rory O’Connor and Dick Barrett were told in their cells at 2 a.m. on Dec. 8 that they would be shot at 8 a.m. (Barrett had been a childhood friend of Hales’s and they’d been in the IRA together in Cork.)

Kevin O’Higgins, who took some persuading by cabinet colleagues to sign the order, defended the executions in the Dáil to charges of vindictiveness from the Labour Party, now the official opposition with the anti-Treaty party absent. “One of these men was a friend of mine,” he said and then collapsed in his seat sobbing, unable to continue. (O’Connor had been the best man at his wedding in October 1921.)

Head of the Provisional Government W.T. Cosgrave, who had once been an opponent of capital punishment on ethical grounds and was himself sentenced to death for his part in the 1916 Rising (commuted two days later), argued that such drastic measures were necessary to save democracy and its institutions in the newly independent Ireland.

On Dec. 10, home of another pro-Treaty TD Seán McGarry was set alight in an attack and his 7-year-old son Emmet died as a result of injuries sustained in the fire. In February, Thomas O'Higgins, father of the minister, was killed by a raiding party that also torched his County Offaly home.

The once accommodating Lynch declared the pro-Treaty side “traitors” in a letter to the political head of the Republican side, Éamon de Valera, after the attacks on the TDs. But the deaths of prominent individuals had been halted, until that is Lynch himself was killed by Free State troops in April 1923. The Civil War ended shortly afterwards.

In 1926, de Valera formed the Fianna Fáil party, and Seán Moylan was among those who joined him; he became a TD again in 1932 and held various ministerial posts during his career.

Next to Moylan in the pictures is Eoin O’Duffy, who was elevated into the Free State’s military leadership by Collins and Richard Mulcahy. He was then appointed commissioner of the new police force, An Garda Síochána, which would be unarmed so as not to involve it in the conflict. O’Duffy was removed 10 years later by de Valera’s Fianna Fáil government, because it felt he was hostile to it.

Said by historians to be a charismatic figure, and the most popular of the pro-Treaty leaders still living (O’Higgins was assassinated in 1927), he was appointed head of the Army Comrades Association, which aimed to provide protection to pro-Treaty supporters from attacks by militant Republicans.

Under O’Duffy, an admirer of Mussolini and his Blackshirts, which had marched on Rome in 1922 and took governmental power, the ACA became the Blueshirts. The government felt he had plans to march on Dublin. His colleagues in the pro-Treaty camp were more worried about his ideas about marching on Northern Ireland and also declaring a Republic. The 1934 formation of a new party, Fine Gael, of which he was made leader, was in part an attempt to rein him in. But it too eventually grew impatient with his unlawful and extra-constitutional methods.

After a Blueshirts misadventure supporting Franco’s rebellion in Spain, O’Duffy explored alliances back home with right-wing extremists on the republican side of the fence, notably in the short-lived Córas na Poblachta in the late 1930s, which also had a few left-wing extremists. He was given a state funeral upon his death in 1944.

Mellows’s advocacy in 1922 of a tactical shift to the left by the Republicans has been much discussed over the decades. Born in England to a non-commissioned officer in the British army, he was raised in his mother’s Ireland. It was said his English father was disappointed that he didn’t follow him into the army, but the younger Mellows, a devout Catholic, appears to have embraced the concept of martyrdom in Ireland’s cause early on in life.

Standing beside him in the picture of the six men was Gearóid O’Sullivan, a second cousin to and close personal friend of Michael Collins’s (and likely his eyes and ears at the Mansion House meeting). The academically gifted O’Sullivan was entrusted by Patrick Pearse with raising the tricolor over the GPO on Easter Monday, 1916. He married Maud Kiernan in Granard, Co. Longford, in November 1922. It had been planned originally as a double wedding with Kitty Kiernan, her sister, and Collins.

O’Sullivan left government service and politics later to concentrate on his career as a barrister. He died at Eastertime 1948, and was given a military funeral on Easter Monday.

In 1929, after he resigned from the army, Mac Eoin was elected a Cumann na nGaedheal TD and thereafter a Fine Gael TD at each election until 1965; from 1932, he was in the opposition to Fianna Fáil administrations except for his ministerial service in the multi-party coalitions of 1948-1951 and 1954-1957. In the presidential election of 1945, Mac Eoin was the Fine Gael candidate against a former Civil War opponent, Fianna Fáil’s Seán T. O’Kelly. He lost that contest and was defeated by de Valera for the same office in 1959.

In March 1957, Seán Moylan gave the oration at the state funeral of Ernie O’Malley, a fellow anti-Treaty IRA leader who’d turned down the offer of a political career. Appointed Minister of Agriculture in a new government later in the spring, Moylan died suddenly in November, a few days short of his 68th birthday, and was also honored with a state funeral (his and O’Malley’s were the only two in the 1950s).

Mac Eoin was given a sendoff with full military honors upon his death in July 1973. Alice Mac Eoin died in 1985.