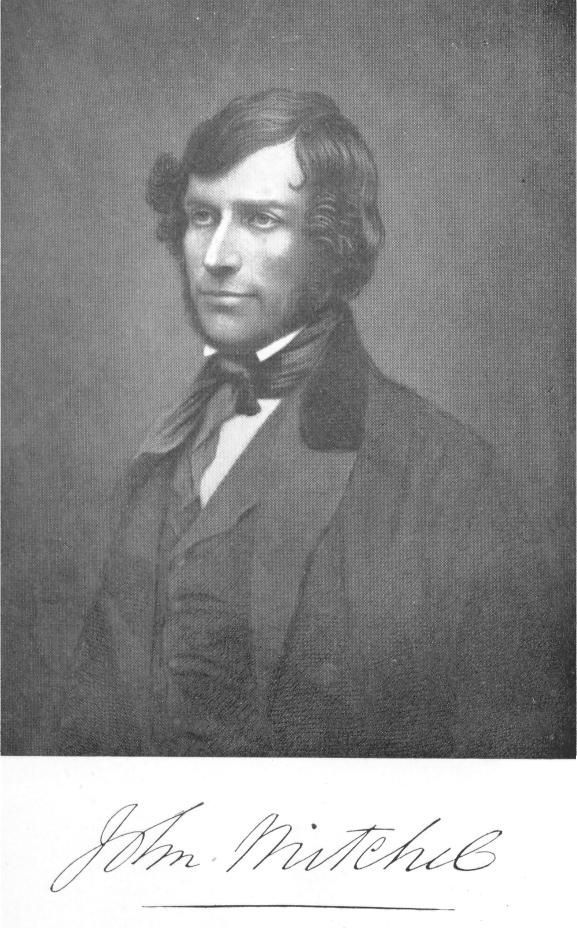

In the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, much has been written with regard to the Derry-born Protestant, Irish nationalist and political journalist, John Mitchel.

This is owing to Mitchel's forceful unapologetic support for slavery which was most vehemently expressed through his writing in mid-nineteenth century America - this following his escape as a convicted felon from Van Diemen’s land in 1853.

There have been calls to rename sporting organizations bearing Mitchel's name, in tandem with a campaign for the removal of a statue to his memory in his boyhood home of Newry, County Down.

Mitchel’s divisiveness where color was the divisive issue has been well established. However, in a purely Irish context, his role in promoting unity where religion was the issue in question has received little attention. It runs very much contrary to, and indeed challenges, the dominant historical depiction of this man as being only a divisive figure.

This Irish context is illustrated specifically in Mitchel's letters to the Protestant farmers, laborers and artisans of the northern counties of Ireland.

The remarkable letter series was published in his United Irishman newspaper during April and May of 1848. The newspaper, with Mitchel as editor, ran from February 12, 1848 for sixteen weekly editions until May 27 of that same year.

The paper was based in Dublin and maintained a readership of over five thousand. The letter series is emblematic of Mitchel’s imagined Ireland where Irish men of all faiths and none would combine in unity to banish from Ireland the destructive influence of the British Empire, and in so doing bring economic prosperity for all.

Mitchel stressed the shared heritage of all Irishmen. Writing in the preface of his seminal biography on the life of Aodh O Neill he argued vehemently: “are not Derry and Enniskillen Ireland’s as well as Benburb and the Yellow Ford."

The existence of an ancient, distinct, noble, Irish race in Mitchel’s worldview is crucial to the formation of his seminal racial hierarchy. It is the foundation stone upon which his controversial racial views emanate, and at this stage in his career his hierarchy was peopled by the noble Irish race at the apex. The ancient Irish race, with their long illustrious history, were central to the formation of Mitchel's worldview and he cites this shared history in a call to unity.

Over the course of his series of letters published in the United Irishman, Mitchel challenged what for him was the root of all evil in Ireland, the British Empire. His anti-imperial agenda is a central tenet of his letter series, and he calls on the Protestant farmers of the north of Ireland to unite with Catholics of the south to bring it to fruition.

He passionately writes to his countrymen in mid-nineteenth century Ireland .

“I called on you to come and help me to abolish the system that gave away the food you raised and the cloth you wove to be eaten and worn by strangers."

Mitchel believed that the greatest threat to the Protestant farmers of the north emanated from the British system of government in Ireland, which allowed for the produce of Ireland to be sold elsewhere to maintain the empire economically. He posed the question: “Seeing that Ireland produces one year with another double as much as would feed and clothe all her people. What becomes of it?”

In writing to the Protestant farmers, laborers and artisans of the north, Mitchel ,in the midst of the famine states tellingly: “I know that hunger is at most of your doors”.

John Mitchel sought to persuade the Protestant farmers of the north that sectarian divisions were a tool of conquest fostered by Britain to encourage division as a barrier to Irish unity. He encouraged his fellow Ulstermen to reject such sectarianism and focus instead on their true enemy, the British system of government in Ireland which had left them in a perilous state.

He succinctly writes “the pope we know is the man of sin and the antichrist and also if you like, the mystery of iniquity and all that but he brings no ejectments in Ireland."

He continued further along the same vein when stating, “The seven sacraments are to be sure very dangerous, but the quarter acre clause touches you more nearly."

The influence of both the United Irishmen of 1798 and the Young Ireland movement under Thomas Davis are to the fore in inspiring Mitchel’s quest for Irish unity.

His efforts in pursuit of unity are characteristic of the ideals and tradition of the United Irishmen of 1798, even allowing for the fact that the origins of Mitchel’s republicanism were quite different and much more classical in nature.

In the pages of his newspaper, he championed the relevance of the United Irishmen most obviously in the naming of his publication, and further with the republican ideals of liberty equality and fraternity emblazoned proudly on the masthead.

The seminal impact of Thomas Davis and the Young Ireland movement is evident in Mitchel’s attempts to educate the Protestant farmers of Ulster with regard to the glorious deeds of their ancestors in his letter series. In alluding to the noble deeds and glorious past of Irishmen of all creeds and none, Mitchel further develops the Young Ireland view of a distinctly Irish, shared history.

Mitchel’s efforts at promoting Irish unity challenge his dominant historical depiction as purely a divisive figure. His negative depiction by the British authorities in Ireland was to be expected considering his attempts, through his writing, to rid Ireland of the British empire.

“They will tell you that I am a Jacobin and an Anarchist and a revolutionist,” Mitchel retorted

To his fellow protestants in an attempt to influence them he stated: “I may be a revolutionist, but you weave and dig for half wages. I am a Jacobin, but you are fast becoming paupers."

In analyzing the complexities of the situation in Ireland, and seeking to bring Irishmen of all faiths and none together in the common interest of all, Mitchel displays a maturity that runs contrary to his negative divisive depiction by the British authorities of his time, and generations of historians since.

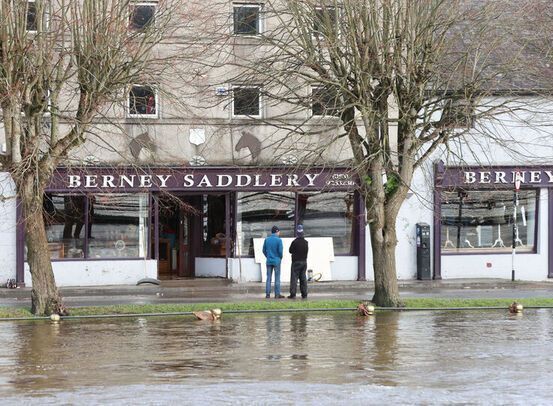

In making his appeals for Irish unity, Mitchel exhibited a prophetic pragmatism of critical significance when viewed in the context of Ireland’s perilous position in the current Brexit debate.

He argued forcefully over one hundred and seventy years ago in his letter series that Irish unity will contribute to enhanced economic conditions for all on the island of Ireland.

A similar argument is being put forth today to insulate Irish people against the potentially negative impact of Brexit.

Further striking comparisons are evident between Mitchel’s letter series and contemporary Ireland. Mitchel raged in 1848 with regard to the province of Ulster: “there is not in all the nine counties a single small tenant right farmer who can say with confidence that his house is his own."

Can this assertion not be applied to young Irish people of today, who, owing to economic hardships and outside interests such as vulture funds, cannot aspire to afford property ownership.

Furthermore, the current resounding calls for an all-Island approach to battle against the Covid-19 pandemic have been striking.

Mitchel’s argument for Irish unity will receive little acknowledgement in the Ireland of today as his name remains shrouded in controversy owing to his indefensible stance in championing slavery.

The Ireland of today was not the Ireland imagined by John Mitchel. The capitalist, commercial society in which we live was demonized by Mitchel as a branch of empire which, in his view, contributed greatly to causing the Famine. T

Tellingly, many of the issues he raised over one hundred and seventy years ago remain both pertinent and unresolved in the Ireland of today.

David Collopy is a Limerick-based final year PHD student in history. His research focuses on the life of John Mitchel and his work has been published in the Irish Times and the Irish Post in London. He also delivered the John Mitchel lecture series 2021 for Newry and Mourne District Council.