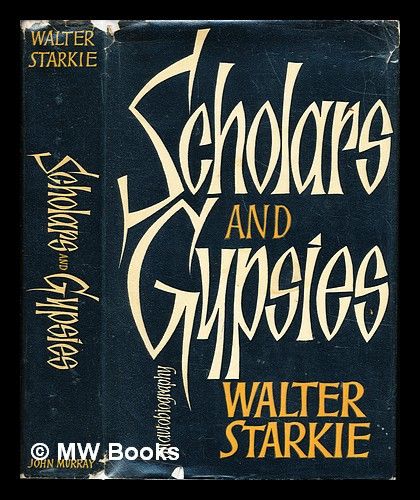

Today the Way of St. James, an increasingly popular pilgrimage trek to the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain not only draws more than 200,000 trekkers annually, but also is inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Irish actor James Nesbitt starred in a film based on making the pilgrimage called “The Way.” Although many people mistakenly believed that the pilgrimage to Santiago has continued without interruption since the Middle Ages, the trek only gained renewed popularity in the late 1950s, thanks in large part to Irish scholar Walter Starkie, whose 1957 classic “The Road to Santiago” became the first popular modern work written in English about the pilgrimage, but he made many other important contributions to Spain and its culture.

Though Starkie is a forgotten figure today in his native Ireland, Spain still remembers him for the many contributions he made as a professor, translator of Spanish literature and as the founder of the massively influential British Institute during World War II. He was, however, much more than an academic. A charming vagabond who spoke four languages fluently, he was proudest of being called “the man who knows about gypsies.” Few men ever succeeded better in combining the respectable academic world with the vagabond life. His popular travel books described his vacations from the academic world, when he slung his violin over his shoulder and tramped the roads of Europe, living with the gypsies as one of them and paying his way with his fiddle.

It's maybe hard to believe that this fiddle-playing rover, beloved by Europe’s Roma community, was actually a scion of the privileged Irish Protestant ascendancy, although raised Catholic. Born in Ballybrack, Killiney, Co. Dublin, Starkie was the son of a noted Greek scholar and translator of Aristophanes, and the last Resident Commissioner of National Education for Ireland under British rule. During his days at Trinity, Republicans accused him of being a “West Briton.”

Starkie graduated in 1920, taking first-class honors in classics, history, and political science. An accomplished violinist, he also won first prize for violin at the Royal Irish Academy of Music in 1913. Due to his severe asthma, he was rejected for service in the First World War, but joined a group entertaining the forces in Italy, where he married an opera singer and complicated his legacy by supporting the initial stages of the Mussolini’s Fascist regime.

He was a friend of William Butler Yeats, who asked him to sit on the advisory board of the Abbey Theater. Starkie often disagreed with the other board members and failed to convince them to stage Sean O’Casey’s anti-war drama “The Silver Tassie,” which led to O’Casey’s abandoning the Abbey. He became a fellow of Trinity College in 1926 and its first Professor of Spanish in 1926. One of his pupils at Trinity was the Nobel Prize winning playwright Samuel Beckett.

Starkie’s life would change with his first trip to Spain in 1924. He gave lectures at the Residencia de Estudiantes, where some of the giants of 20th century Spanish culture studied, including the playwright and poet Federico Garcia Lorca, for whom he played the violin, film director Luis Buñuel, and painter Salvador Dali. The Spanish quickly fell in love with him because he appeared to be a figure from a bygone age, in which the wandering scholar had a sound knowledge of languages, music and literature.

A great story-teller who enjoyed his wine and music, Starkie most loved Spanish parties where music took center stage and people would break into spontaneous flamenco. He charmed Spaniards by busking for his food at the café tables of Antequera or walking around Madrid with his fiddle slung over his shoulder. He would shock some of his more staid Irish and British friends with the effusive greetings given him by wild looking gypsies who loved his music. Few recognized him as a professor. Once, calling on the Basque painter Ignacio de Zuloaga, he looked so disheveled that the painter’s servant slammed the door. Starkie responded by sitting down on the painter’s doorstep, taking out his violin and playing the painter’s favorite Basque tune, to which the painter responded by opening the door, laughing, and greeting him with a bear hug.

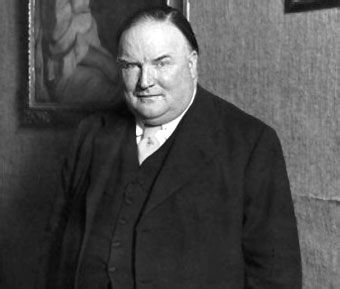

Walter Starkie.

In the 1930s, he wrote a few successful travel books, “Spanish Raggle-Taggle: Adventures with a Fiddle in Northern Spain” (1934) and “Don Gypsy: Adventures with a Fiddle in Barbary, Andulusia and La Mancha” (1936). Because of the many influences of his youth, Starkie would take on very different personas in his travel books: sometimes Irish, sometimes English, sometimes just a wandering minstrel or a fiddler. These works chronicled his interactions with all classes of people in Spain, which few other travel writers at the time did. He also spent a great deal of time with Andalusian gypsy musicians, chronicling their music and listening to their stories. Writing gave him the chance to indulge in his passion for travel and music; for instance “Don Gypsy” is subtitled “Adventures with a Fiddle in Southern Spain.”

Walter Starkie's enduring ties with Spain took firmest root during the years 1940-54. Like many other Irish Catholics, Starkie was a backer of Franco during the Civil War and because of his support of the Falangist movement, the dictator had no objection to his 1940 nomination as representative of the British Council to Spain. Starkie founded the British Institute in Madrid and was also appointed Britain's cultural attaché. The Institute thrived due to Starkie’s amazing personality, in stark contrast to the haughty staff at the British Embassy, which did little to foster warm ties with the Spanish people. His many Spanish admirers quickly acclaimed him the most dynamic and most productive ambassador of good will ever to have served the Spanish and English-speaking nations. On any evening during Starkie’s tenure at the British Institute, one could meet Madrid’s cultural elite including Pio Baroja, future Nobel Prize winning novelist Camilo Jose Cela, painters like Ignacio de Zuloaga and many others. He founded branches of the British Institute in Barcelona, Bilbao, Valencia, and Seville, taught comparative literature at the University of Madrid, and lectured in almost every other university in Spain.

Thanks in part to Starkie’s outsized influence, Spain remained neutral during the war. During the war, he also helped set up and operate an escape route for British airmen shot down over France. Starkie and his wife also allowed their large flat at number 24 Calle del Prado to be used as a safe house for escaping Jewish refugees.

Starkie helped to popularize Spanish literature in the English-speaking world, publishing his translation of “Don Quixote.” He was fascinated by the image of the Andalusian pícaro, the rogue or chancer who made a living by conniving.

In 1954, he reluctantly left for the United States where he taught in several universities, but he always kept a home in Madrid, where he planned to retire. He returned to Madrid in 1970 and lived there until his death in 1976. His body was brought home to Ireland and now rests in the family tomb in Dublin.