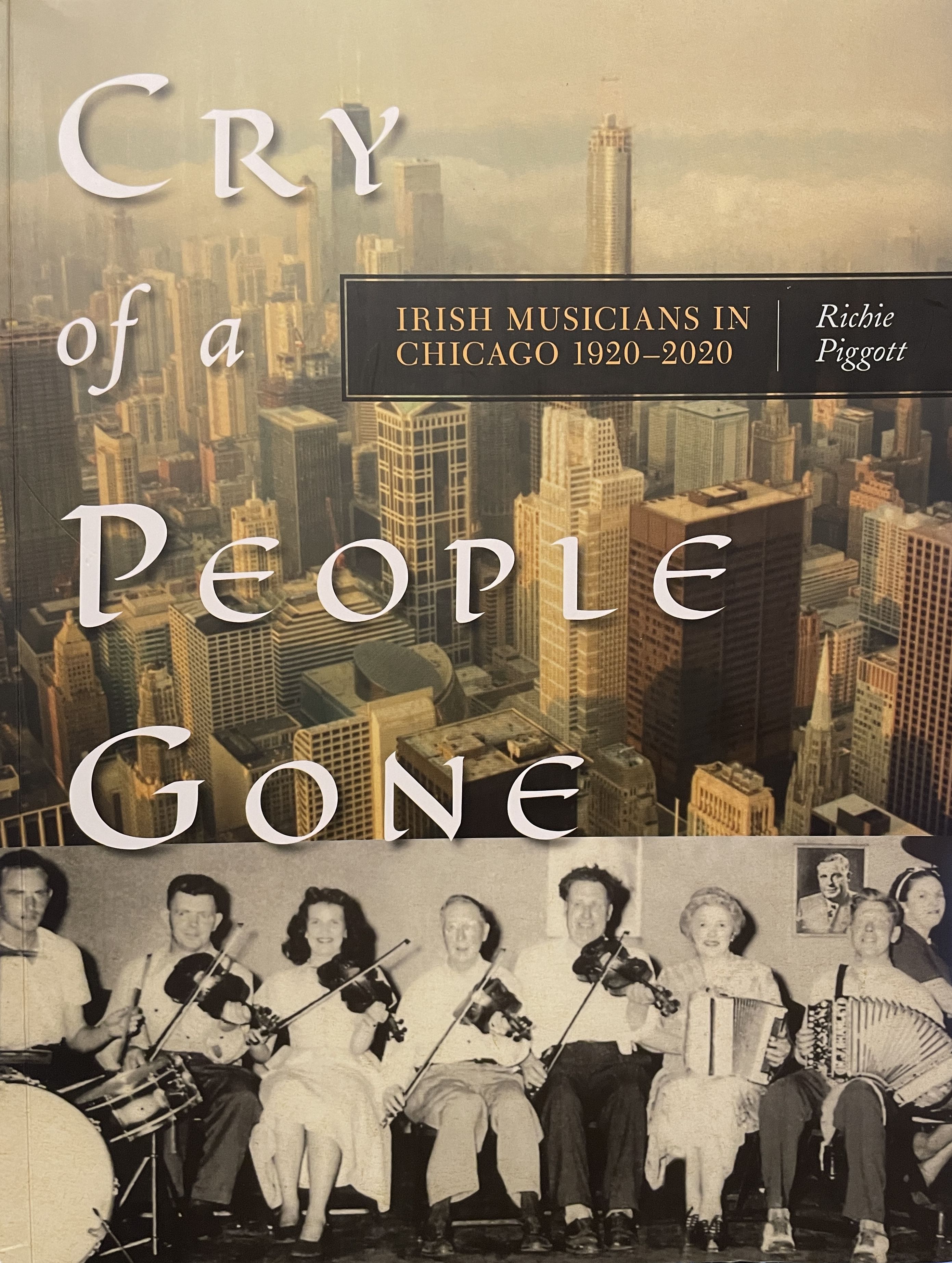

A quite remarkable book recently came my way called “Cry of a People Gone: Irish Musicians in Chicago 1920-2020” by Richie Piggott. The result of “10 years of research into the family history and music of Irish immigrants and some of their children who came over to Chicago over the past 100 years,” the book is, first and foremost, a lovingly researched history that illuminates details of the experience of Irish music in America over a century. However, the dozens of photographs and figures it includes and its fairly large format (8.5” x 10.5”) gives it a coffee table book feel that makes the written history more accessible. In short, this is an important work that covers a lot of ground and it deserves a place in every library of Irish music.

Originally from Cork and for the last 25 years a resident of Chicago, Piggott has a deep, abiding love for traditional music. Although not a player himself, his musical bona fides are nevertheless strong. His father Johnny (originally from Dooks, Co. Kerry) was an accordion player and his mother and her family (Dingle) were all heavily involved with marching bands. Their love for music rubbed off onto Richie – as well as his brother Charlie, a brilliant musician and member of the supergroup De Danann – and motivated him to dive into the music’s history in a way few others have endeavored.

What Piggott’s done for Chicago music here is amazing because he really changes the game. For example, the great Francis O’Neill, whose work put Chicago on the Irish music on the map, is largely absent from the narrative. But this is not an issue, as plenty has been written about O’Neill before. What Piggott does instead is gives overdue attention to the people and organizations that brought Irish music in Chicago to the fore in O’Neill’s wake, and in doing so he’s done a most admirable job.

The book includes six chapters, an epilogue, and a pair of appendices and opens with a fabulous foreword from longtime director of the Irish Traditional Music Archive Nicholas Carolan. Chapter One, “Early Chicago and Irish Immigration to America,” looks at the experience of Irish Immigrants in the developing city and beyond. It’s short and direct with some good detail that leads to the far more substantive second chapter, “Irish Traditional Musicians in Chicago, 1920-1945.” Covering the pre-WWII era, chapter two examines nearly 20 musicians and includes a section looking the pipers and pipe makers of the time. Biographies about the likes of Pat Roche, Jimmy Neary, Eleanor Kane Neary Johnny McGreevy, Tommy & Anne Cawley, Frank Thornton, and many others are included and serve not only as reflections of the subjects’ personal lives, but give insight into events and organizations that defined the music being made over the 25-year period covered here.

The story continues in chapter three, “New Irish Immigrants in Chicago after World War 2.” This chapter is divided into two sections, “Chicago Southside” and “Chicago West & Northside,” and profiles over 30 musicians, including the great Kevin Henry, Malachy Towey, Paddy & Johnny Cronin, Joe & Seamus Cooley, Kevin Keegan, Noel Rice, Jimmy Coyle and many, many others. A list of music venues are included for each section as well. Again, new light is shed on the musicians profiled here and when taken as a whole gives the reader a new perspective on Irish music in Chicago in the post war era.

Chapter four is called “The Irish Musicians Association of America” and is particularly interesting to me because it tracks the formation and growth of the Irish Musicians Association of America. Although not the first Irish music club in the United States, it is of particular importance because its goals were closely aligned to those of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann and the first real effort to organize traditional musicians and pre-existing clubs into a national body. This chapter is the first real telling of this story and a most welcome surprise.

Chapter five, “Frank Thornton’s Tours,” looks at a pair of tours Thornton organized in 1959 and 1969. In the first, he brought a group of American musicians, singers and dancers over to Ireland for a monthlong tour “to demonstrate that the playing of traditional Irish music by American-born players was alive and well in Chicago.” This tour seems unthinkable today and was was received remarkably well. In the second, he organized a two-week tour of Irish musicians called “Ireland’s Concert of Champions.” Again successful, it presaged the Comhaltas tours that began in the 1970s. Brilliant stuff that really sheds incredible light on the type of work Thornton did in those days.

Chapter six, “History of the First Fleadh Cheoil in America, Chicago 1964-1969,” is an accounting of a series of pre-Comhaltas competitions held under the auspices of the Irish Musicians Association in the mid-and-late 1960s. Although short, the chapter provides basic but detailed information about how the competitions came to pass and includes 22 pages of photographs that documents these events for the first time in any sort of accessible way.

The book’s epilogue closes the story by by identifying the generation of musicians that learned from those covered more fully. Liz Carroll, Jimmy Keane, Marty Fahey, John Williams, and Michael Flatley are among those mentioned. It’s a brief section, but a logical conclusion given the scope of the book.

“Cry of a People Gone” is brilliant. Substantial in feel, it’s an incredible marriage of primary source and archival material that tells an engaging story about Irish people and music in America. Piggott’s expansive research reveals an impressive gallery of musicians who helped shape traditional music and it covers a lot of very interesting ground along the way. The only case study I can think to compare it to is Susan Gedutis’s “See You at the Hall: Boston's Golden Era of Irish Music and Dance,” which looks at Irish music in Boston through a somewhat similar, but also somewhat narrower, lens. Ultimately, this is a truly outstanding book that every fan of Irish music should own, especially those with a connection to Chicago. The history is well crafted and it’s brought to life with the assistance of dozens of well curated and rare images. (I know it’s a bit early to be thinking of it, but if you’re looking for a Christmas gift idea for the traditional musician in your life, you wouldn’t go wrong with this!)

“Cry of a People Gone” can be ordered through www.richiepiggott.com. And do keep an eye on that space, as Piggott’s indicated he plans to upload his entire archive to it. Exciting stuff!

Finally, if you’re not familiar with TG4’s program “Ceol ón Chlann” (“Music From the Clan”), now’s the time to give it a look. Episode 5 this season, called “Na Vallely’s,” is all about the Vallely family and takes a closer look at JB & Eithne Vallely’s work with the Armagh Pipers Club, Dara Vallely’s work with the Armagh Rhymers, and that of other members of the Vallely family (including NYC resident Cillian Vallely). It’s a fantastic look at an impressive musical family. Other episodes from the current season include profiles of the Haydens, the Glackins, the MacConnells, the Gavins and others. You can stream them all through TG4’s website, www.tg4.ie.