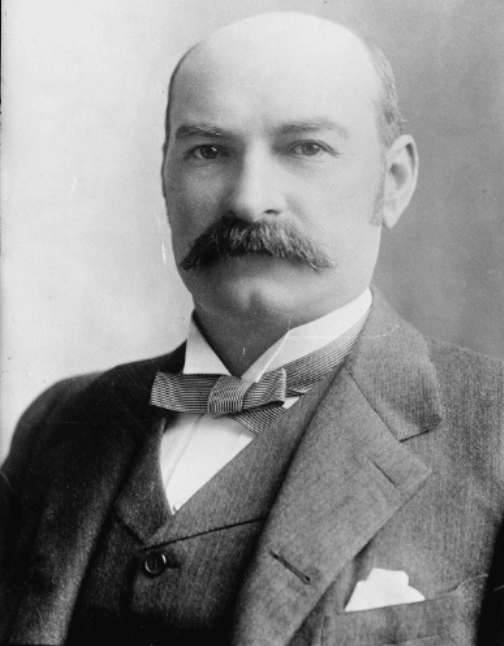

Like many other Famine refugees, John McDonald’s rise from poverty to great wealth and fame seems more like a fairy tale than an authentic biography. Against long odds, McDonald succeeded in constructing New York's first subway line (between City Hall in Downtown Manhattan and 145th Street in Harlem) in the early 1900s, which at the time was considered an engineering marvel.

Born in Cork in 1844, McDonald moved to New York when he was just 4 years old at the height of the Great Hunger. His father Bernard settled the family upstate and worked on building the NY Central Railroad. A hustler the New York Times praised for his “untutored native intelligence,” John followed his dad into the construction business, and it was not long before McDonald was managing construction sites. His first job was the construction of the Boyd Corners Reservoir in Putnam County. He was then appointed the Inspector of Masonry for the New York Central’s Fourth Avenue Tunnel, which began construction in 1872. The expertise he gained on this job would make him a nationally renowned expert in building huge tunnels.

In the 1880s, McDonald achieved nationwide recognition for finally completing the construction of the nearly five-mile-long Hoosac tunnel, which was hailed as the most stupendous tunnel ever constructed in the country. McDonald’s team employed dynamite for the first time in tunneling, and his experience with the explosive would help him in building New York’s subway system.

After gaining prominence for his work on the Hoosac Tunnel, McDonald decided to start his own firm. In 1889, his firm was hired to build the Howard Street Tunnel for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and he employed two Irish subcontractors, the McCabe brothers, who successfully completed the long tunnel and helped the firm burnish its reputation as the country’s cutting-edge tunneling firm.

In 1898, he completed the Jerome Reservoir in the Bronx, but New York then was buzzing about one the most ambitious construction project since the building of the Erie Canal, the construction of its subway system. Although fifteen firms bid for the huge project, McDonald had an advantage; he was Irish in a city dominated by the Irish American political machine, Tammany Hall. McDonald successfully bid $35 million, which was more than $1 billion today. McDonald had promised to build the subway line in four and a half years at a cost to the city of less than $ 36,500,00, and even to equip it with rolling stock.

Building the subway, however, presented monumental engineering and construction challenges. McDonald was presented with the daunting challenge of building the city's first underground rail line, while also avoiding the city’s serpentine network of sewer, water, and electrical lines. He also had to make sure that the foundations of nearby buildings were not weakened or damaged during construction. Finally, he had to build it along one of the city’s main thoroughfares, and do so that the job disturbed business there as little as possible.

There was also a controversy about how to build. Some said that they should tunnel under the ground, as they had in London, while others said that they should dig a hole build the subway line and then fill in the earth. McDonald employed an efficient technique called “cut and cover” - a time saving process that involved blasting the streets with dynamite at night and employing daytime crews to clear away the rubble using mule carts. When the debris was cleared, another team of workers would then cover it with the displaced rubble and dirt, before laying a layer of fresh pavement on top of it. Though his solution was hailed for its brilliance, McDonald modestly claimed the job was “Nothing more than building a string of cellars, end to end.”

The job was not easy. There were labor disputes and controversies about materials. The backbreaking work also took the lives of 16 workers as a result of tunnel collapses and accidents. Employing a team of most Irish American subcontractors, McDonald completed the nine-mile stretch of track on-schedule and it was opened to the public in October 1904 with great fanfare. Newspapers hailed the subway system he had built, and an estimated 150,000 people paid the five-cent fare to ride the subway on its opening day. Within four years, the city's subway system had stretched over 23.8 miles.

Constructing the subway had not only made MacDonald famous, but also rich. He made uncounted millions on the subway contract and made another three million on land that he reclaimed using the earth from the tunnel digging project. His vast wealth allowed him to purchase a residence in the famed Dakota building, a far cry from the Irish cottage he was born in.

Thomas F. Ryan, head of the Metropolitan Street Railway, hired him away from the IRT in 1905 in hopes of building a rival line. However, numerous disputes over property rights and ownership of routes stalled the projects, and McDonald never built another subway line. He became so prominent that his name was even mentioned as a builder of the Panama Canal, but he never took part in this historic endeavor.

McDonald died on St. Patrick's Day in 1911 and a New York Times obituary hailed him saying, “The poor Irish lad, with little scientific culture, but taught in the school of experience, achieved where others had deliberated, hesitated, and failed even to attempt."