On July 31, 1936, a priest, the Rev. Thomas Patrick Lynch, died in Taos, N.M.

A reporter from Santa Fe wrote: “Two years ago, the young Irishman from Detroit had made the journey up to Taos for the first time. Full of hope he was starting his life’s work in the missionary parish.”

Katharine Darst described the sad funeral procession down the mountainside, and what she saw on the way to the Cathedral of St. Francis of Assisi in Santa Fe.

“But nowhere was there a Willa Cather to mark the passing of this boy. She who had felt so poignantly the death of an old archbishop with his life work accomplished, was not here to witness the infinitely more pathetic exit of this boy whose life had been shut off ‘ere half his days were done.’ Here was a sorrow which needed her pen, and alas, only I was there.”

Darst sent a copy of the article to the priest’s brother, Edward, in Detroit.

If the death of a young priest was noteworthy enough for his Irish family, it would take on added significance. For Edward Jr., who at age 10 was the only child pictured in a large group at Fr. Lynch’s ordination in Detroit, would at 12 wander into the basement of a funeral home to see his dead uncle being dressed in a fresh white alb and green chasuble in preparation for the wake that night and 10 o’clock Mass at St. John’s the next morning, Thursday, Aug. 6, 1936.

“That vision — a young boy’s witness of a dead priest and living men lifting him into the casket — shaped his life and my life and my family’s life for going on seven decades now,” according to his second son writing in the early years of the 21st century.

Instead of becoming a priest himself, Edward Lynch Jr. followed his true vocation, and most of his nine children followed him into the business he founded.

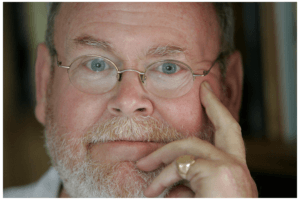

Thomas Lynch, the son named for the priest, has been a funeral director in Milford, Mich., since 1974. He is also in the “poetry business,” as his cousin Nora Lynch, of Moveen West, Kilkee, Co. Clare, used to say. He happily embraced the two vocational identities, and also took easily to being Irish as well as American.

In the first case, having an interesting day job only raised his profile, especially in the early 21st century when the HBO drama “Six Feet Under,” set in a family-run funeral home, was a hit with viewers and critics alike. He’d written two books — “The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade” and “Bodies in Motion and at Rest: On Metaphor and Mortality” — that the show’s creator Alan Ball admired.

“These two collections of essays about life as an undertaker gave me a sense of the tone I wanted the show to have,” he said, calling Lynch a “brilliant, soulful writer.”

“You funeral types have always understood,” Ball told him in an email. “Once you put a dead guy in the room you can talk about anything.”

Lynch also understands that his own tribe have a particular affinity for the process: “For the Irish and Irish-Americans. the only spectacle more likely to bring out a crowd than a blushing couple at the brink of their wedding is a fresh corpse at the edge of its grave.”

‘Sentence commuted’

As for that second coupling of identities, by the time he wrote “Booking Passage, We Irish and Americans” (2005), he had more than paid his dues in his ancestral land, having been coming and going for 35 years.

“In the late 1960s, my life was, like many American men my age, up for grabs,” Lynch writes. A draft lottery was held on the first day of the last month of the decade. Sept. 14 was the first date drawn. “Men born on that day were going to war,” he says. His birthday, Oct. 16, was pulled out 254th. “It was like a sentence commuted,” he recalls. “I was free to go.”.

He would not be sent off to an unwinnable war. Instead the 21-year-old asked his widowed grandmother for the address of her husband’s relatives in Ireland, folks she’d dutifully sent Christmas and Easter greetings to every year. They were the “distant old-country cousins” who were mentioned in their prayers: “Tommy and Nora Lynch on the banks of the River Shannon. Don’t forget.”

The brother and sister were both unmarried and the end of the line. Tommy was to die in 1971, the year after he met his American namesake in person. Nora lived on another 21 years, during which time Lynch was witness to a radical transformation within the cottage’s walls, though the landscape would largely stay the same.

In time, Thomas Lynch became next of kin to Nora, his first cousin, twice removed.

Circumstances can make that connection a close one; because, first of all, it involves two siblings. In this case, Nora’s father was Sinon, and the brother who left and settled in Michigan was Tom, father to the priest, and great-grandfather to the poet.

I can relate. Mary, my great-grandmother, raised her eight children in Dublin, my mother’s father among them. John, Mary’s brother, was father to eight children on the farm in West Clare. Their first-born daughters were educated and accomplished — Mary’s Kate had an important clerical job and John’s Mai was a nurse. These cousins, both single, could be trusted one summer during World War II to bring safely an extroverted 7-year-old Dubliner down to the farm in West Clare. The child, my mother, was enraptured by her three weeks there, and talked about that vacation and all subsequent vacations and trips until the day she died in 2019.

Mai would become godmother to my sister, her little first cousin, twice removed. Mai’s brother, Michael, was my only relative in New York when I arrived in 1993. And a welcoming one he was, too,

Part of my West Clare family’s story involves Loop Head. John and Mary’s grandmother was from a house just beside the lighthouse and she walked barefoot the 12 or 14 miles inland on her wedding day. Her elderly descendants referred to her in the late 20th century as the "woman from the west.”

Lynch mentions Loop Head, of course, and the Victorian resort Kilkee and the old market town of Kilrush. But it’s the family homestead that has pride of place in his heart.

“Nora Lynch’s house, four generations removed from the young man who left there in 1890 and who started our family in America, fills me with a sense of the grandeur of Time,” he wrote in a long letter to Síle de Valera, a government minister and a local member of the Dáil, after Nora’s death.

The Land Commission had made Nora a squatter on her own land under pressure from local “grabbers” and “blackguards.” It would eventually be resolved, with the land going to a couple she was close to. Thomas Lynch, meantime, had inherited the cottage, which had been a wedding gift in the era of the Famine to “our common man,” as he called their shared male ancestor, Nora’s grandfather, Pat Lynch, who died in 1907 when she was 4 or 5.

The lighthouse at Loop Head.

Luxury lost

Lynch writes: “Can the bigger picture be seen in the small? Can we see the Western World in a western parish? Can we know the species by the specimen?” Well, not so much really, for the book tends to focus on and reflect a particularly Irish-American sensibility.

“It was in Moveen I first got glimpses of recognition, moments of clarity when it all made sense—my mother’s certain faith, my father’s dark humor, the look he’d sometimes get that was distant, preoccupied, unknowable,” Lynch says. “And my grandmothers’ love of contentious talk, the two grandfathers’ trouble with drink, the family inheritance of all that.”

A couple of decades on, when his brother came to help him with Nora’s funeral, he was able to view this with a certain distance: “Ireland happened to Big Pat in 1992 the way it happened to me in 1970, as a whole-body, blood-borne, core-experience; an echo thumping in the cardiovascular pulse of things, in every vessel of the being and the being’s parts, all the way down to the extremities.”

Lynch recalls about Pat, “‘Oh God,’ he half-sobbed through the shambles of his emotions, ‘to think of it, Tom, the truth and beauty of it.’

“I remarked to myself, given that the brother and I were both occupationally inclined to get through these solemnities while maintaining an undertakerly reserve, I thought his emotings rather strange.”

At the heart of all this is a search for authenticity.

“Instead of Methodists or Muslims, we are golfers now; gardeners, bikers, and dead bowlers,” he writes, “The bereaved are not so much family and friends or coreligionists as fellow hobbyists and enthusiasts.”

He adds, “And I have become less the funeral director and more the memorial caddy of sorts, getting the dead out of the way and the living assembled within a theatre that is neither sacred nor secular, but increasingly absurd—a triumph of accessories over essentials, gimmicks over the genuine. The dead are downsized or disappeared or turned into knickknacks in a kind of funereal karaoke.”

Lynch had been thinking for a while about writing a sort of “Roots” for the Irish, celebrating those who left and those who stayed. Then all changed the year he began writing it. After 9/11, Americans had lost, he says, the “luxury of isolation and purposeful ignorance of the larger world of woes, a taste for which I’d acquired in my protected suburban youth and overindulged throughout my adulthood—fattening, as Americans especially do, on our certainty that it will all be taken care of by whoever’s in charge.”

Much later in another context, he discusses certainty, or certainties, and someone being in charge and “watching out for the likes of me.”

He says, “But faith, it turns out, is not child’s play, seasoned as it must be by the facts of life — love hurts; we die; hope falters; God, it seems, goes missing sometimes.

“This is where the smarmy and narcissistic doxologies of the day fail us. Faith is not for dealing with God’s grandeur — the sunset, the candle flame, the child’s face. God is manifest in a lover’s eyes. Faith is rather for the hours of God’s absence, when we are most alone, betrayed, in pain, afraid.”

Lynch has great affection for the old-school priests of his youth, like family friend Fr. Thomas Kenny, who was from Galway.

On her deathbed his mother “saw Fr. Kenny, dead himself for fifteen years, coming to take her by the hand into heaven. She saw him plainly, called him by his name, and smiled beatifically when she told us about it all.”

Fr. Kenny had retired just as the Vatican II reforms were being discussed in the American church and went home to Ireland. “He found the Irish Church much as he’s left it years before—much as I’d found it in 1970, established, in charge, completely enmeshed with the life of the nation, and its people.”

Lynch seems less impressed with the latter-day priestly caste, or at least not with the first-name accessibility and the fashion fails and the scandals, accompanied by a doubling down on certain aspects of doctrine. “Divorce and abortion and contraception would seem, I am not the first to say,” he writes, “odd topics for manly celibates to get so embroiled in.”

He recalls an encounter with a young English priest of Irish parentage on the island of Iona. The American traveled up on impulse when on a trip to England. “I’d always wanted to see this place,” he says.

He revealed to his new acquaintance that Mary, whom he’d married recently, was caring for his four children back home in Michigan. No, his first wife was not dead, and, no, he’d never gotten an annulment. And he went to describe the idyllic relationship with Mary and some of the details of their wedding.

“‘Of course, that was only a “civil” marriage,’ Fr. Peter said.

“‘Well, that would be an improvement on the one before,’ I told him.”

There are other great lines like that and some memorable paragraphs.

Here is Thomas Lynch on the attitudes to weather in the corner of the world he made his part-time home: “‘Grand day, thank God,’ is what they mostly say, grateful to be up and out in it. Or ‘soft day,’ or ‘it’s very broken.’ One rarely hears the out-and-out complaint that the weather in West Clare is severely damaged compared to, say, Cuba or Connecticut, or Melbourne, or East Clare, where trees can stand and gardens thrive and people can go about their business.”

For more about Thomas Lynch’s four books of essays, five collections of poetry and a book of stories, visit thomaslynch.com