Pope Francis, who won the support of two thirds of voting cardinals when elected eight years ago, is photographed in 2015 with President Barack Obama, a rare commander in chief to get two consecutive popular majorities. [Official White House Photo by Pete Souza]

By Peter McDermott

“All through the hot and sultry night those who had taken positions of leadership in party affairs labored among themselves in the effort to find some solution of the problem of selecting a suitable candidate for President.”

This is how the New York Times opened a story about the problem solved on the 10th count at the Republican National Convention in Chicago.

Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding, a moderate conservative in party terms but liked well enough by the GOP’s strong progressive wing, was tapped to be the standard bearer in the 1920 presidential election. Massachusetts Gov. Calvin Coolidge would join him on the ticket.

Later the same summer, the Democratic Party took 44 ballots in San Francisco to settle on Gov. James M. Cox, also of Ohio, as their man. That gathering, the first nominating convention ever to be held on the West Coast, chose 38-year-old Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt as his running mate — which meant that three of the four on the major-party tickets were future presidents.

As New York City implements ranked-choice voting for some key electoral contests, it’s useful to remember that shifting support from one contender to another in an effort to get to 50 percent plus one — a majority — is not foreign to America's political traditions.

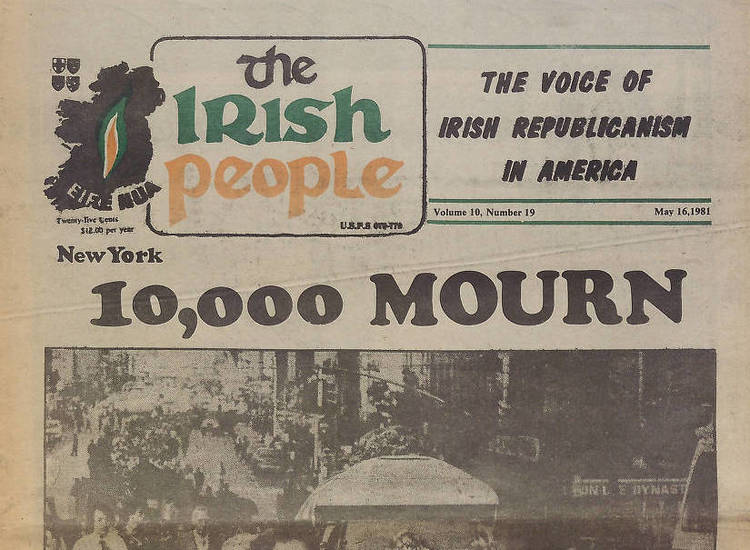

No delegate was ever sent home early in the days of the smoke-filled halls and backrooms; the job at hand had to be done first. Similarly, no voting cardinal in good stead has been told to pack his bags ahead of two-thirds agreeing on a new pope and white smoke being released into the Rome sky.

Now, the New York City voter can more fully participate, all the way to the finish line — most notably in the mayoral primaries — just like the delegate in the convention hall in times past or the cardinal in the Roman conclave.

Crowded primary

“It’s an awful lot of fun,” said Council Member Daniel Dromm of ranked-choice voting on his Facebook page, citing school-board elections of the past and other contexts.

He was hosting an April 29 training, at which guest Eric Friedman of the city’s Campaign Finance Board told the Facebook Live/Zoom event that RCV “invests a lot of power in the voters.”

One could say, indeed, that RCV offers more agency for voters than the system used in the Chicago and San Francisco conventions a century ago. In that era, first of all, there was no process that could automatically eliminate the often many candidates who had just a handful of delegates’ votes; secondly, as the Times reported in the above case, the shifts and breakthroughs were generally the result of a decisions made in the smaller meeting spaces or hotel corridors and rooms.

In the contests set for late next month, the New York voter can give a clear set of instructions for various eventualities simply by listing up to five candidates in order of preference. Most attention is focused on the crowded Democratic primary in the mayoral race, as it’s assumed the victor will go on to lead the city from January 2022 through January 2026.

Gothamist, the news and culture website owned by WNYC, is explaining the workings of the system with a feature called “Practice Ranked-Choice Voting With Our Big Apple Book Ballot.” (You can participate here.)

Voters can rank up to five works of New York-set fiction from a list of 13. WNYC’s “The Brian Lehrer Show” on Thursday morning did a limited mini-version of this with listeners phoning in. “Catcher in the Rye” won.

Echoing Dromm, Lehrer said, “This really is fun with the books.”

It’s useful to understand that RCV brings the process of choosing a candidate closer to the reality of market-based decision-making — that is, if we think of the consumer as the electorate, which has to be content with the outcome. When you set out to purchase a car, you may go through a complicated process before settling on your final choice. The same generally occurs when helping your first-born child acquire a college place.

In contrast, the simpler plurality-based system, the predominant one in this country, can throw up results that are somewhat at odds with what the electorate/consumer actually wants, as mentioned in a previous article on the subject.

From the perspective of a market model, it can only be guaranteed to work effectively if there are two candidates. Once there are more, it complicates matters greatly and as often as not, in such circumstances, candidates are elected with the most votes but short of a majority. It’s interesting to note that in the 50 years or so since America joined the community of nations that guarantees all of its citizens voting rights, only two presidents have won consecutive majorities of the popular vote — Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama.

The pope, though, must receive two thirds of the electorate and that tends to happen in a process that takes place over several ballots.

One vote to give

Various American institutions and corporations protect their legitimacy internally and externally with such methods of voting. It makes sense for the Oscars, for example, to use RCV — the Best Film, or any other category, must reflect the view of the Academy and not that of the enthusiasts for one production.

There is one thing that doesn’t change between the plurality system, which the U.S. is most accustomed to, and RCV: you the voter have just one vote to give; you've an equal vote with everyone else who participates.

Perhaps there are a few who think they have five votes somehow, and that accounts for their voting 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 for their favorite candidate. Another error is to give two or more candidates the same ranking.

Each number doesn’t accord with a ballot, or round as they’re called in the New York context, but rather for each time your position shifts. So if your No. 1 preference has the least amount of votes and is eliminated, your No. 2 preference is now your vote. And No. 3 is your vote when your No. 2 exits and so on. So, the most important thing to remember is that any lower preference you indicate cannot be used, ever, against a higher preference.

If you vote No. 1 for the ultimate winner, or indeed runner-up, then it’s part of the aggregate total until a result is declared and your lower preferences are not used.

You may feel super loyal by not indicating 2nd, 3rd preferences etc. but you’re actually depriving yourself the opportunity to continue participating if your No. 1 choice is eliminated. In any voting situation with multiple rounds or ballots (such as in the papal conclave or with the Oscars), people are happy to continue voting, and the 2021 candidates themselves will likely use the ranked-choice option.

But you can stop at your No. 1 choice or at 2, or 3, or 4. There is no need to fill in all five ovals on your ballot paper. There is certainly no need to vote for someone you don’t like.

As for voting with your heart: well, the system is designed in part to accommodate that. You may decide to vote for a less-fancied candidate because he was a school friend of your brother’s, or she has a good position on a policy that’s dear to you, or you want to make a general anti-establishment statement.

However, in the case of the biggest race, someone’s going to be mayor, and the stage at which you pivot toward indicating which of the leading contenders you prefer will likely depend on the strength of feelings involved. You may believe that a No. 1 for a no-hope candidate is indulgence enough and that you should then get on with the business of choosing a mayor. Or, maybe you’ll feel that none of the top tier is worthy of your vote or it doesn’t matter too much which of them wins. Or you may like to vote ideologically with your No. 1, 2 and 3 preferences and then consider other factors, such as competency, for the No. 4 and 5 preferences. Your options are myriad.

The piece of advice above about not voting for someone you dislike is hardly absolute, of course. There might be a case for giving, let's say, a fifth preference to someone you don’t at all care for to stop someone you think would be a disastrous choice. Again, it’s important to reiterate that that fifth preference only comes into play when your first four preferences have been eliminated from the race.

The “lesser of two evils” will always be involved to some degree. Often, though, people use that term because they don’t feel invested in the process that led to the choice being offered them. But if it’s part of a more involved approach, they tend to be happier, as Doris Meyer suggested in the previous article. The former elementary-school teacher recalled having her students use ranked-choice voting to select the type of meal they’d have for their holiday party. “They were always satisfied with the outcome,” she said.

And, as Mr. Dromm and Mr. Lehrer have agreed about RCV, it’s fun.