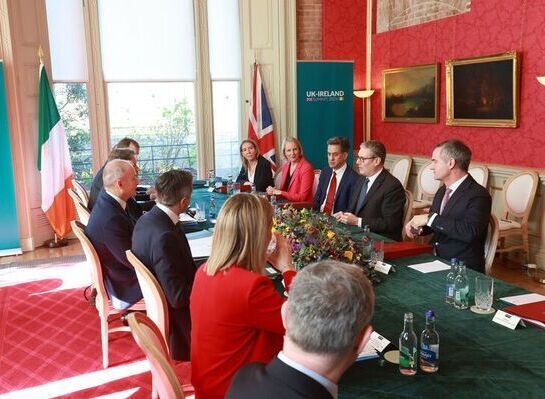

President Bill Clinton pictured in 1999 with USAF Col. Paul Fletcher.

Between the Lines / By Peter McDermott

A line jumped out from the radio last Friday morning that said a lot about our current predicament. Actually, it was spoken two years ago by a guest on WNYC’s “The Brian Lehrer Show.” The program that day — to give something of a breather for the great host himself and his staff — was a Summer Fridays presentation, specifically archived material from a series in 2018 that looked at America’s culture wars as seen in years ending in 8. Among the four years discussed on Friday was 1998, most of which was preoccupied with the President Clinton/Monica Lewinsky scandal.

The guests on that segment were Bill Schneider, former CNN analyst and author of “Standoff: How America Became Ungovernable,” and Jane Eisner, who oversaw the editorial page of the Philadelphia Inquirer at the time.

“We’ve had four presidents before Donald Trump, each of whom promised to heal the country, to bring the country together,” Schneider said. “The first George Bush said he would be ‘kinder and gentler.’ He got fired after one term. Bill Clinton was supposed to be the ‘third way’ and a ‘New Democrat.’ He got impeached. The second George Bush said he was a ‘uniter not a divider,’ and look what happened under him, and, of course, President Obama said there’s ‘no liberal America, no conservative America, just the United States of America,’ and he was wrong. The country, after each president remained more and more divided, which convinces me that the problem wasn’t Clinton and the problem wasn’t Obama, the problem is the problem.”

Trump, Scheider said, is “unique” in that he got elected by dividing the country and governing as a divider. He saw it as a business opportunity.

The author asked the rhetorical question: can it change? “What can really matter,” he said, “and it’s a bit shocking to say, is if we have a crisis. The only time that the country really pulled together was one year after 9/11. This overwhelming crisis left the country in shock and for one year a majority of Democrats supported President Bush.”

That lasted until the following September when Bush “announced the rollout of the Iraq War.”

Schneider added: “Generally speaking the solution to governance is that in a crisis this country works very well.” And that’s the line that jumped out at me.

Lehrer said back in 2018, “Well, let’s hope it doesn’t take that since a crisis usually involves really bad things happening to a lot of people.”

The radio host was absolutely right, but the CNN analyst on this occasion didn’t really take all possible scenarios into consideration. Two years on, every country is experiencing the same crisis and the U.S. has been doing worst among the wealthier nations, by a long way. Maybe, Schneider was thinking of some crisis post-Trump when we’d again have an administration that wasn’t utterly weak and incompetent.

Lehrer said that on the issue of the Clinton/Lewinsky scandal, the Democratic Party’s position is evolving. A conservative caller, a father of eight daughters, said that the feminist movement’s support for Clinton was a “big mistake.” Lehrer asked Eisner if the feminist movement and others “paid a price,” and she said yes, in retrospect. but added there were critics of Clinton in his own party. Eisner’s paper called for the president to resign because he appeared to lie under oath, but later opposed impeachment because of the political context. Clinton was supported by a two-to-one majority in the country and it would be wrong, the Inquirer reasoned, for the other party to force him from office.

Washington, though, quickly gave up on Clinton, and was ready to declare Gore the new president with possibly Diane Feinstein as his vice president. “If there had been no polls, President Clinton could not have survived,” Schneider said.

‘Open secret’

A caller raised in France said there was a long history of presidents in that country “having a mistress and even a child on the side” and people weren’t so worried about it. Really? This surely is a case of missing a lot of context to the point where history gets reinvented.

The French media, by convention, respected the privacy of public figures. But this was rapidly breaking down by the mid-1990s. In November 1994, the magazine Paris Match published photos of 78-year-old President Mitterrand leaving a restaurant with a 20-year-old woman named Mazarine Pingeot. They were taken by paparazzi — who’d been on the case for months — at a distance of 500 meters. The photo spread was condemned by the rest of the media and politicians of all parties. Pingeot was the president’s daughter, the only child in his “second family” with partner Anne Pingeot, an art historian. The politician began the affair in 1965 when she was 22 and he was 49. In 1974, the year of Mazarine’s birth, presidential candidate and ultimate winner Valéry Gisgard d’Estaing tried to throw the socialist off in a TV debate with a random reference to Anne’s hometown, as “a place Mr. Mitterrand knows well.”

President Francois Mitterrand with President Ronald Reagan at Omaha Beach, France, in 1984. The ceremony was part of the 40th anniversary of D-day commemorations.

Mitterrand worked hard to keep his dual domestic arrangements — involving his wife Danielle and two adult sons and Anne and their daughter — from public view. It was, no doubt, an “open secret” within state security, political and journalistic circles. The tendency, in such circumstances, is that the much broader group of people who hear the rumors tell themselves afterwards that they were in on the “open secret.” But how could they have been if it wasn’t referred to in the media and they didn’t personally know any of the individuals involved?

Friends speculated about why Mitterrand didn’t seek a divorce. One reason, they felt, was that he and Danielle had lost their first son in infancy in 1945, and such a tragedy can forge an unbreakable bond between a couple. The second was egoism: he chose Danielle and wasn’t going to give her up, officially at least (she had a long-term relationship with her husband’s blessing). But, there was also the political calculation — a divorce might be a disadvantage for someone with an eye on national leadership. While his wife grew up in the secular left, Mitterrand’s own family and his partner Anne’s both came from the old France: it was upper-middle-class, Catholic and provincial. He surely didn’t want to unduly antagonize that part of the electorate.

Bill Schneider said that for conservatives Clinton represented the new America, the one forged in the 1960s. No matter how much he compromised with Republicans on economic issues and governed from the center, they saw him as the symbol of all that they opposed, values wise. Monica Lewinsky was a godsend for them, but the public was unfazed. That’s the term Mitterrand biographer Philip Short uses about the French public’s reaction to the photos in Paris Match. The citizens were unfazed. But then, that was in 1994. What if it had been 1974?

Mitterrand kept another secret for years from the French people. Just months after he was elected president of the republic in 1981, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and was told that it had metastasized to his bones. His father had died of the disease and an ashen-faced president, looking at the floor, told his doctor, “I’m done for.” The doctor replied that he wasn’t. He could be dead in months or he could last three years; a few rare cases lived beyond that point. The president told Anne that night. His wife, the official first lady, found out with the rest of the country 10 years later. Mitterrand would serve two seven-year terms and die a half-year into his retirement in early 1996. Did he have the right to keep it a secret for so long? Is transparency always the proper course? Does the public have a right to know every detail of one’s private life? If you’re running a country, is it in the public’s interest to have your personal life on display like a long-running soap opera?

Eleven years ago I interviewed in New Jersey the 105-year-old County Galway-born Sr. Victor, aka Mary Waters. How had the world changed since she was a young woman? I’ll paraphrase her answer: “More freedom, less privacy.”