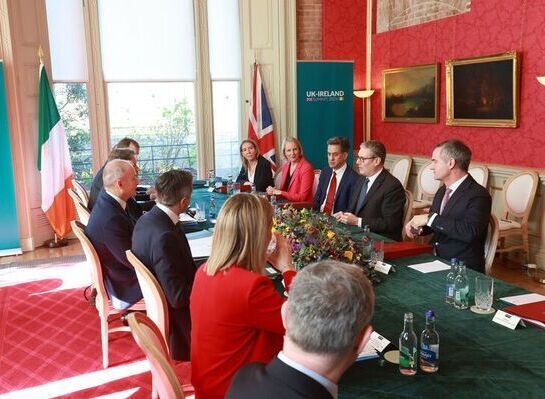

When they relocated to the West Clare house her grandfather had been born in, Chris Williams and her novelist husband Niall Williams’s new friend Mary told them: “Clare is good for music.” PHOTO BY WESTCLARE.NET

By Niall Williams

Sometime after Chris and I first arrived in West Clare, in the mid-1980s, I became aware that one of the county’s foremost attractions was invisible.

It was no less real for that. Our warmest welcomer in Kiltumper was Mary Breen, a true gentle countrywoman who had been married to a cousin of Chris’s, a Spencer Tracy lookalike, Johnny Breen, who died of a heart, as they say. Like many of the older people, in Mary were preserved the antique courtesies of welcome. We had come from New York to make a life in Clare, a life of writing and painting was what we dreamed, in the house where Chris’s grandfather had been born. We were young. Listening to our dream, Mary didn’t pass comment but her eyes sparkled, and then she asked us: “Do ye like music?”

Now, at that time, music to us was Van Morrison and Joni Mitchell. It was something that was at a remove, out there, at a radio distance, as it were. It came from the speakers. By which I mean I never associated any of the music I listened to with a place. So, when we answered that yes, we liked music, and Mary said “Clare is good for music,” it was a foreign idea to me.

Back then, I was largely ignorant of traditional Irish music. I can’t offer reasons why, other than the fact that, growing up in Dublin, I maybe couldn’t find where the music belonged to me, or I to it. I couldn’t quite find any footing in it. Nor, not coincidently, could I in Ireland, and soon enough I was gone to New York.

But now Chris and I were in Clare.

Naively, I asked Mary where we’d go to find the music.

“You could find it anywhere,” she said. Mary didn’t drive a car. The ambit of her “anywhere” was not vast.

“Would you come with us, Mary, if we went looking for it?”

“I would, Niall. I’d love that.”

One summer’s evening, a week later, the three of us went in search of music. We had a big old blue Peugeot and set off up the west coast of Clare. The given destination was Doolin, which, 35 years ago, was already a legendary locus for traditional music. But really, we might stop anywhere along the way, and ‘There could be music, Niall. There could.’

In the back seat, looking out the window, Mary had a traveller’s delight in seeing places that were beyond the limits of her bicycling. “Miltown is good for music,” she said, as we came down the main street of Miltown Malbay. I kept an eye out for the lesser-spotted musicians, and tried to accommodate inside myself that idea of a place good for music.

What did it mean exactly?

Well, what I came to understand was that it meant there had been music here. A wonderful seisiun had sprung up, maybe in Friel’s last Friday, or up in Clancy’s on the Sunday—'”You should have been here then”—and the music, although physically over, outlived itself, and grew an aura, the way marvels do.

Added to this, was the uncertainty of whether any music would happen at all. In those days there were few organised, advertised sessions. The musicians were like birds and could land anywhere. They were, in the pure sense of the word, amateurs, playing for love, (and free drinks and saucers of cigarettes) and mostly for themselves.

With Mary, we went into a dim pub on the main street of the town. There was no music. But there had been, “Gorgeous music, two nights ago,” said the barman.

“Now, Niall,” said Mary, delighted.

Well, that day, the musicians were on clocks of their own construction and didn’t appear, so we drank our minerals, got back in the car, and headed out the coast road once more.

North of the long beach at Lahinch, we came upon a big man in his 70s thumbing a lift. He had a flat cap sitting on the top of his large head. He was also wearing an ass’s collar. It was a large dark leather oval hoop, and, to save him holding it, he had hung it around his neck.

“Will we stop for him, Mary?”

“We will.”

We pulled over and he got in beside her, placing the ass’s collar between them. He was a genial man, shining from the effort of walking a bit out of the town until he’d decided he’d chance the thumb. Not everyone would pick up a man with an ass’s collar, he said, smiling across at Mary. “The collar burst and lost hair and was rubbing the ass wrong.” He’d taken it to a man for repair. “Good job he did too,” he said, touching the stitching.

He carried on talking as we drove up past the Cliffs of Moher, then round my favorite bend in Ireland, where suddenly you see the Aran Islands laying out in the bay, and on to Doolin where he told us he lived.

“Ye’re going to Doolin yourselves?”

“We are.”

“For the music, so.”

“Yes.”

He said no more until we came along the road above the village and he said, “There’s my house now.” It was a small low farmhouse tucked in a bit from the road, a donkey standing on the grass in front of it. He opened the door of the Peugeot, but then he turned and said: “You don’t know me, I suppose?”

“I do,” said Mary.

“Who am I so?”

“You’re Micho Russell.”

He grinned with delight. “I am.” He was one of the most celebrated tin whistle players in the country. “I’m sorry now I haven’t the whistle with me, to give you a tune as thanks for the seat.”

I was about to say that was all right, when he said, “But I’ll give ye a lilt.” And immediately, he started lilting a reel for us. Now, it wasn’t something I had ever experienced before. The car door open on a salt breeze, eyes shut and forehead gleaming, Micho Russell lilted a jig. It was neither instrumental nor song, not humming, not whistling, but a kind of mouth-music that flowed out of him, both in perfect time and out of all time. Both other-worldly and, not only of this world, but of this very place.

When he finished, we were too stunned to say anything. He took the ass’s collar, gave a short wave behind him and headed in to the donkey.

“Now, Niall. Now, Chrissie,” said Mary. “You see,” her eyes said, “in Clare you could find music anywhere.”

And in the years since then, we have. Whether, on a large scale, during the extraordinary week-long Willie Clancy Summer School in Miltown Malbay, say, where in the afternoons the musicians flock into the town, finding purchase wherever they can, playing on walls, on windowsills, on the hoods of cars; or, if the day comes wet, in any corner that will stave off the thirst and keep an instrument dry. Or, on the small scale, a single fiddler bent ear to the bow on a stool beside the fire in Egan’s in Liscannor.

The music is at home here, is what I realized. It is at home, and when at home it can do what it wants.

Nor has any of this really changed in our nearly thirty-five years here. “Clare is good for music” is as true a statement now as it was when Mary first said it. And “it could be found anywhere” probably also as true.

Given this, it was not surprising that when I came to write my new novel, “This is Happiness,” which is set in a west Clare village in the late 1950s, I would want to honor some element of this by making traditional music a part of a novel. And so, one strand of the story becomes the quest of the two central characters to hear the legendary Clare fiddler, Junior Crehan. Perhaps not surprising either that as I wrote I listened, almost by way of soundtrack, to where Irish music has recently gone, the literally spell-binding music of The Gloaming. Here in Kiltumper, I wrote, often with the front door open, so Chris could hear while working in the garden, making actual that idea of place and music, and giving a nod to the ghost of Mary who told me that, in Clare, “the music, is in the air.”

Niall Williams’s latest novel, “This is Happiness,” will be published in the U.S. on Dec. 3.