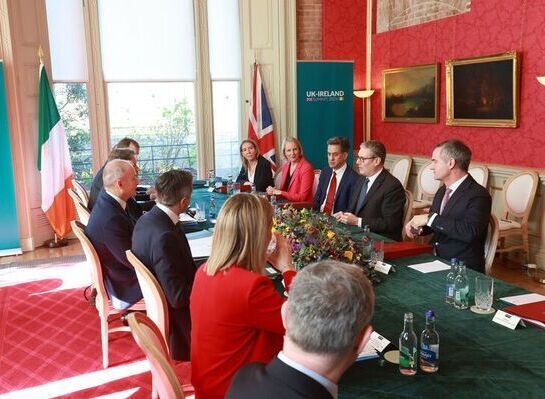

Anne Griffin’s debut novel is “When All Is Said.” PHOTO BY JOHN BOYNE

By Peter McDermott

Louise Aronson, geriatrician and professor of medicine at University of California, San Francisco, recalls being at a new trendy restaurant crowded with people waiting for a big-name author event to begin. Her guest was her mother, who killed some time talking about the couples on either side of them.

“‘Mom,’ I said pointedly, giving her a look that was meant to signal that not everyone has hearing loss and the people whose dress and behavior she was commenting on were right beside us.

“Don’t worry,” the daughter was told, “I’m invisible.”

Aronson relays this in her book “Elderhood,” which was published in the summer of 2019 and is subtitled “Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life."

She offers a few quotes from prominent older writers on this issue of invisibility, with an emphasis on white males, a group that generally notices its onset later than others.

Roger Angell, World War II veteran and New Yorker magazine writer for the past 75 years, said in an essay, “When I mention the phenomenon to people around my age, I get back nods and smiles. Yes, we’re invisible. Honored, respected, even loved, but not quite worth listening to anymore.”

Aronson says: “In old age, even the brilliant, famous, and fairly unimpaired are ignored.”

Caoilinn Hughes’s debut novel is “Orchid & the Wasp.” PHOTOGRAPH BY DANIJEL MIHAJLOVIĆ

So, against that backdrop, it’s interesting to see quite a few middle-aged or younger Irish writers of literary fiction putting the voices of sympathetic older characters front and center in new work.

One can point, for example, to “The Heart's Invisible Furies” (2017) by John Boyne, and Niall Williams’s “This is Happiness,” which will be published here on Dec. 3. But then, Boyne and Williams are both well-established novelists.

How can we account for those who have the desire and confidence to do the same at or near the beginning of their careers? At least two who had a novel published in the U.S. in 2019 fall into that category. Anne Griffin’s debut “When All Is Said” is seen through the eyes of Maurice Hannigan, an 84-year-old County Meath farmer. And, Dan Mooney, having won acclaim for his first novel, “Me, Myself and Them,” in which he tackles the issue of mental illness, for his second, “The Great Unexpected,” tells the story of Joel Monroe, a former mechanic and successful garage-owner in his late 70s and living in the Hilltop Nursing Home; there, he makes an unlikely alliance and friendship with new resident Frank Adams, a former TV soap actor. Both Griffin’s Maurice and Mooney’s Joel are grieving for a deceased spouse.

I asked the two novelists if they took this road with some trepidation.

Dan Mooney’s second novel is “The Great Unexpected.” PHOTO BY GLIC MEDIA

“None at all,” said Griffin, a native Dubliner who lives in County Westmeath, “I had a very clear image of Maurice in my head. I knew his voice from the off. I knew his life and his motivators and I knew almost instantly how he'd react in any given situation. Having a father of 84 years of age at the time helped immeasurably. It gave me insights into concerns that might not have occurred to me given I was 44 and a woman.”

Mooney, 35, said, “I didn't feel any trepidation really, but I think that's because the book was written almost as a response to the infantalization and trivialization of older people — so I knew I wouldn't be writing a story that denigrated them, or trespassed too boldly on someone else's patch.”

The 34-year-old Caoilinn Hughes, whose debut “Orchid & the Wasp” was published here in 2018, has had a different experience.

“In my case, I haven't written the life of an older person. I've featured older characters in my fiction, but they've never been the central character,” said the Galway-born writer, who won an O. Henry Award on this side of the Atlantic in 2019. “Perhaps it's telling that the one time I tried to write a short story from the perspective of an older -- 70-year-old – man, I simply couldn't do it. I don't expect I'll attempt it again for another decade.”

Hughes recommended three questions asked by American novelist and essayist Alexander Chee: “1. Why do you want to write from this character’s point of view? 2. Do you read writers from this community currently? 3. Why do you want to tell this story?”

The New Yorker magazine said in an admiring review that Hughes’s novel is “hyper-focussed on a single character. Its protagonist, Gael Foess, is a ruthless, fast-thinking beauty…”

When Hughes referred to older characters, she meant those somewhat older than the writer herself, including Gael’s mother whom “readers end up loving or hating,” and her father who “takes great pleasure in the existence of and dancing around ethical blind spots.”

There is a pivotal person in “Orchid & the Wasp” who is in the same age bracket as Maurice and Joel — Wally, an extremely wealthy American in his 80s Gael meets in first-class on a transatlantic flight.

Answering one of Chee’s questions, the novelist said about Wally: “Historical events have impressed a certain narrative upon his life, which fundamentally differentiates his worldview from Gael's. I wanted to shine some torches into that chasm.”

That attention to detail is perhaps one reason the novelist John Banville, 40 years Hughes’s senior, praised “Orchid & the Wasp” as an “ambitious, richly inventive and highly entertaining account of the way we live now.”

Asked about possible pitfalls in depicting older characters, Hughes said they would be exactly the same as a “writer can fall into when writing any character: undermining their humanity through lazy writing by privileging assumption over observation.”

Addressing that same issue, Mooney said: “I believe that writers have to place themselves into shoes they may not otherwise fit in to write, but should be wary of where they walk in those shoes. Remaining sensitive to the ‘other' whose perspective you're writing from doesn't, no matter what edgy comedians tell you, mean that you have to stifle creativity. In fact it encourages it, forcing writers past lazy stereotypes and making them, challenging them, to observe their characters and plots from angles they may not have considered before.”

He continued, “I thought a lot about both of my grandfathers, who the book was dedicated to, and tried to imagine their reactions to indignities. Considering them, keeping in mind the friends I have in Young Munster [a rugby club in Limerick] and in theatre in Limerick, some of whom are elderly people, I managed to steer me around the pitfalls. I would hate to have written a book that makes light of the real issues older people have with autonomy and independence.”

People Magazine said, ”Griffin's stunning debut, brimming with irresistible Irish-isms, is an elegy to love, loss and the complexity of life."

The author herself said, “In ‘When All Is Said,” I wanted to show the value of older people. I wanted to present their wealth of life and wisdom that somehow I feel is not so much ignored but undervalued in our society. Youth is given due credit and rightly so, but equally, I believe, should life experience."

She added, "I made Maurice a strong, single minded, canny man for a reason. I truly believe our Western societies need to look to other cultures who value their older citizens more, who sit at their coat tails listening to what it is they have to say in order to enrich their world. Let's face it, right now we can use all the help we can get, for example, my mother at 85 is the best environmentalist I know. She wastes nothing, lives on just enough and doesn't have a greedy bone in her body.”