Stephen G. Butler.

Page Turner / Edited by Peter McDermott

Stephen G. Butler had on his bedroom wall during his youth in Woodside, Queens, a “posterized pantheon” purchased one summer in East Durham that contained images of Wilde, Shaw, Yeats, Synge, O’Casey, Joyce, Behan and others. He noticed often over the years the same “Irish Writers” poster at various Irish bars around the five boroughs and beyond.

Butler was puzzled, then, when as a graduate student he read Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s seminal 1963 essay “The Irish” suggesting that those “Protestants, agnostics, atheists, socialists, communists, homosexuals, drunkards, and mockers” didn’t traditionally have much appeal for people from the Irish-American Catholic lower-middle classes (the young scholar’s own background).

And respected commentators in more recent times backed up, anecdotally at least, the view that Irish literature’s biggest names didn’t get much of a look-in when it came to the construction of Irish-American identity.

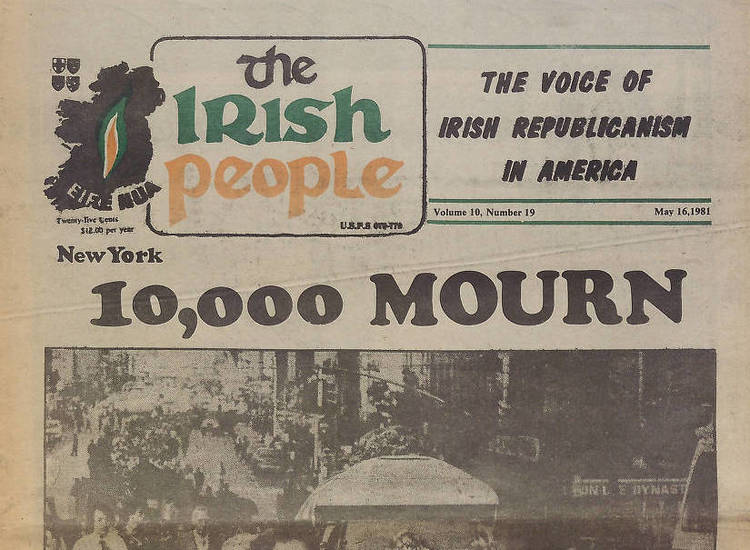

So Butler, who now teaches in the Expository Writing Program at NYU, decided to examine just how some of the pantheon were written about “within the pages of Irish American newspapers, including the Echo, and Irish Catholic magazines.”

“Irish Writers in the Irish American Press, 1882-1964” shows a picture that is “more complicated” than Moynihan and the others would have it and does so, according to one admiring fellow author, “with writing that is relaxed, clear and detailed.”

The academic, who has degrees from Iona College, City College and Drew University, believes for his part that to publish a book, just as with raising a child, “it takes a village,” which in this instance included his parents and all those teachers who encouraged his interest in literature.

And in addition to family members, other academics and researchers, editors and his publisher, he acknowledged assistance from another source.

“Before my teaching career, while I was in graduate school, I spent seven years as doorman/concierge at an apartment building in the Financial District,” Butler told the Echo, “I won a union scholarship from the Local 32 B-J Training Fund that helped me pay for my PhD.”

Stephen G. Butler

Date of birth: Nov. 14, 1978

Place of birth: Woodside, Queens, New York City

Parents: Matty Hugh Butler, Anne Butler, nee O’Connell.

Spouse: Erin Butler, nee Donovan

Children: Daughters Brigid, Lily and Adare

Residence: Northern New Jersey

Published works: This is my first book, though I’ve written articles for New York Irish History (the annual journal of the New York Irish History Roundtable), and along with Gerry O’Shea and the late John Garvey, I helped edit “The 1916 Easter Rising: New York and Beyond,” which was published by the United Irish Counties Association.

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

Teaching full-time and helping to raise three young children is not a great recipe for a regular writing routine. I’m not sure if an ideal universal writing condition exists; each writer has to figure out what works individually and just keep plugging away.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

The journey to publication can be a long, frustrating one, so one has to maintain faith in the quality of the work and hope that the right editor and publisher is out there. I was very lucky to eventually find my way to the great team at UMass Press.

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

Returning home from a family vacation in Ireland during the summer of 1993, I purchased, at the Shannon Duty Free, a bargain book housing James Joyce’s “Dubliners,” “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” and “Ulysses,” all in the one volume. For the next few years, with the help of Cliffs Notes borrowed from the Maspeth Library, I struggled through all three texts. The world that Joyce conjured, the urban world of the Irish-Catholic lower-middle-class, and in particular, the mental universe of a sensitive, brooding boy, were so familiar, and yet so strangely and so beautifully rendered.

What book changed your life?

Though my adolescent rebellions were much less dramatic than those of Stephen Dedalus, it’s no hyperbole to say Joyce’s work inspired me to pursue an individual intellectual path that I might have never taken without encountering his fiction.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

In my experience, many writers, but especially Irish and/or Catholic ones, feel a kind of awe and envy in the face of Joyce’s art.

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

After all these years, Joyce is still the writer with whom I’d most like to have chat, preferably over a bottle of white wine.

What book are you currently reading?

Currently, I’m reading a fascinating book, “I Know That I have Broken Every Heart,” by Diarmuid Curraoin. The author, who teaches Irish at a secondary school in Dublin, argues, against the consensus of the professional Joyce industry, that Joyce was semi-fluent in Ring Irish, and that this dialect is a secret language of “Finnegans Wake.”

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

As my father comes from Sligo and my mother comes from Kerry, I’ll have to name two favorite spots in Ireland: the long, lovely strand at Enniscrone and the stunning cliff-side vistas of Kinard, on the Dingle peninsula.