Alfred Hitchcock, pictured in 1955, directed a screen version of “Juno and the Paycock” in 1930.

By Peter McDermott

“Juno and the Paycock” was performed for the first time on March 3, 1924, at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. Set during the Irish Civil War, which had ended the previous spring, it would become in the words of a 21st century commentator the “world’s favorite Irish play.”

On Saturday night, its latest New York run begins as part of the Seán O’Casey Season at the Irish Repertory Theatre.

"This is our third production at the Irish Rep over our 30 years and each time we find new layers to peel and the rewards are rich and exciting and profound,” said co-founder and producing director Ciarán O’Reilly. “I think ‘Juno and the Paycock’ ranks among the greatest plays of the 20th Century.”

As part of the O’Casey season through May 25, the Irish Rep is also producing the two other plays that with “Juno” comprise the Dublin trilogy: the War of Independence-set “The Shadow of a Gunman” and “The Plough and the Stars,” which has as its backdrop the Easter Rising in 1916.

Said O’Reilly, who is currently directing “The Shadow of a Gunman,” which will run through the end of the season: “There is nothing quite like performing in an O’Casey play. The words throb as they come tumbling from the heart. You feel you are immersed in a very real and sometimes violent world that belongs in its time —yet it is timeless.”

O’Reilly added about the first of the Dublin trilogy, “The powerful women that dominate ‘Juno’ were written years ahead of their time and have a particular relevance these days as gender equality is finally being addressed in a meaningful way.”

It’s been a sometimes difficult road for O’Casey and “Juno” over the 95 years, with some interesting chapters and plenty of controversy along the way.

In his recently published “Irish Writers in the Irish American Press, 1882-1964,” Stephen G. Butler explains some of the personal and political background: “Inspired by the labor leader Jim Larkin, [O’Casey] joined James Connolly’s Citizen Army, but quit when he saw that nationalist goals were usurping socialist ones. He did not take part in the Easter Rising, and his three Dublin tenement plays dramatized the terrible human cost of revolutionary violence and civil war on Dublin’s laboring poor.”

By the time of the debut of “The Plough and the Stars” in 1926, O’Casey had become a favorite target for nationalists. On Feb. 11, members of the audience – widows such as Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington among them – rioted in protest at what they saw as the desecration of the memory of the Easter martyrs. (Interestingly, the socialist Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, who was not a participant in the Rising and was shot dead with two unionist journalists in Portobello Barracks, had many of the same concerns as O’Casey about the drift towards violence in 1915 and early 1916).

Stephen G. Butler is the author of “Irish Writers in the Irish American Press, 1882-1964.”

Referencing a similar reception for “The Playboy of the Western World” in 1907, the Abbey’s W.B. Yeats addressed the audience: “Is this going to be a recurring celebration of Irish genius? Synge first and then O'Casey."

With rather less controversy and fanfare, “Juno and the Paycock” was brought to the screen in 1930 in Alfred Hitchcock’s second talkie.

The Master of Suspense knew some of the backdrop to the play, not least because he was acquainted with one of the two men who fired the shots in a killing that ignited the Civil War. And he had Irish roots himself – his mother being a Whelan and his father’s mother a Fitzpatrick.

Patrick McGilligan, a prominent film historian and biographer, wrote: "The Hitchcocks were staunchly Catholic, but they showed irreverence for everything, including Catholicism. [They] had a number of priests in the family; relatives or not, clergymen were in and out of the home, drinking, singing, laughing and making mischief."

The future film director was educated by the Jesuits at St. Ignatius College where a boy a year or two older than him named Reginald Dunne was a popular leading student. Dunne went off to the Great War and upon his return joined the IRA in London. On June 22, 1922, Dunne and a fellow war veteran, Joseph O’Sullivan, who’d lost a leg at Ypres, assassinated Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson on his doorstop in Eaton Square. Presuming that the assassins were connected to the anti-Treaty force holed up in the Four Courts in Dublin, London put pressure on General Michael Collins, the head of the Provisional Government, to take action against it, which he did within days.

Milwaukee native McGilligan, who focused on the director’s Catholicism in his 2004 biography, said the Hitchcock family also very likely knew the parents of Edith Thompson, who was convicted of killing her husband. Many Britons believed her to be innocent. The biographer argued that the executions by hanging of Dunne and Thompson in 1922 and 1923 had a lasting influence on his work.

Hitchcock’s film version starred Maire O’Neill, the stage name of Molly Allgood, who was J.M. Synge’s girlfriend in his last years (the ill-fated romance is a subject of Joseph O’Connor’s 2010 novel “Ghost Light”), and her sister Sara Allgood as Juno. Barry Fitzgerald, who became closely identified with O’Casey’s work in the U.S., made his screen debut in the picture.

Within a couple of years, the Abbey was touring America with “Juno and the Paycock” and “The Plough and the Stars.”

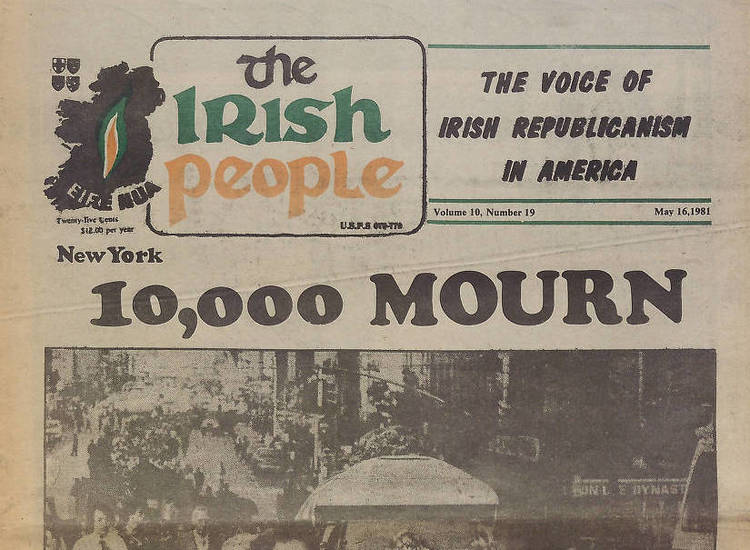

Butler writes, “Not surprisingly, these tragic plays that so powerfully and provocatively challenge the ideologies of physical force nationalism—even if they were performed as character comedies and starred the irrepressible Barry Fitzgerald — were greeted with circumspection by republican elements within Irish America.”

However, there was to be no rioting or any real public protest of the sort there had been for “Playboy” when it arrived in New York in 1911. Instead, certain groups passed a resolution complaining of the plays’ “filthy language, drunkenness and prostitution,” which was sent to the Irish consulate.

Former Abbey actor Barry Fitzgerald in Hollywood in 1945.

O’Casey’s work found defenders in a group of actors called the Irish Theatre, which, the New York Times reported, sent a strong resolution of support to the consulate.

The government’s subsidy to the National Theatre was the issue here. Eamon de Valera -- defeated in the Civil War but a decade later the head of government -- noted that some Abbey plays were the cause of “shame and resentment among Irish exiles.” A compromise was found, says Butler, with “all programs distributed in America stating that while the Free State government subsidized the Abbey Theatre, it could not accept responsibility for the repertoire.”

In defending the banning of O’Casey’s experimental “Within the Gates” in Boston in 1934, some Catholic commentators attacked the Dublin trilogy. For example, the Rev. Terence L. Connolly said in the Jesuit magazine America that in “Juno” et al the playwright had “violently attacked patriotism and every other manifestation of idealism in his native country…with all the devastating cynicism of an embittered propagandist.”

A generation later, O’Casey was still dividing Irish-American opinion. In 1960, letter-writer Edmund O’Rourke denounced in the Advocate “presentations which unjustly degrade, humiliate and ridicule the Irish people, their faith and their national aspirations. The latest and perhaps most offensive in this series is O’Casey’s ‘Juno and the Paycock’ lately seen on Channel 13 T.V.”

A review of David Krause’s “Sean O’Casey: The Man and His Work” in the Aug. 6, 1960, issue of the Irish Echo took a similar line. Says Butler: “The gist of the notice is that Krause overlooks O’Casey’s communist leanings because he is ‘a sympathetic American liberal’ who agrees with ‘O’Casey’s opposition to Irish nationalism and formal religious worship.’”

Frank O’Connor (a Kerry-born lawyer and community activist not to be confused with the short-story writer from Cork City known by that pen-name) wrote in the same issue of the Echo a generalized critique of O’Casey and Brendan Behan, which even suggested that “Seano’s psyche” was formed by his growing up a poor Protestant among poor Catholics.

John J. Regan, of Brooklyn, addressing O’Connor later in the letters columns of the Echo, defended the two Dublin writers: “Your remarks regarding the state of Irish literature, particularly the works of Behan and O’Casey, strike me as strange given the praise heaped upon them lately.”

Butler says, “A fair bit of that heaping, it must be noted, was being done in the Irish American press.”

The tide was turning slowly. The Thomas Davis Irish Players, a community theatre society founded in New York in 1933, eventually staged its first O’Casey play, “Juno and the Paycock,” in 1972.

In contrast, the Irish Repertory Theatre began in 1988 with O’Casey – a production of “The Plough and the Stars.”

“We have a long history with O’Casey at the Irish Rep,” O’Reilly said. “And now we are very honored to devote half of our 30th season to this great master where our plans are to present all of his work in some form.”

For more information, go to irishrep.org.