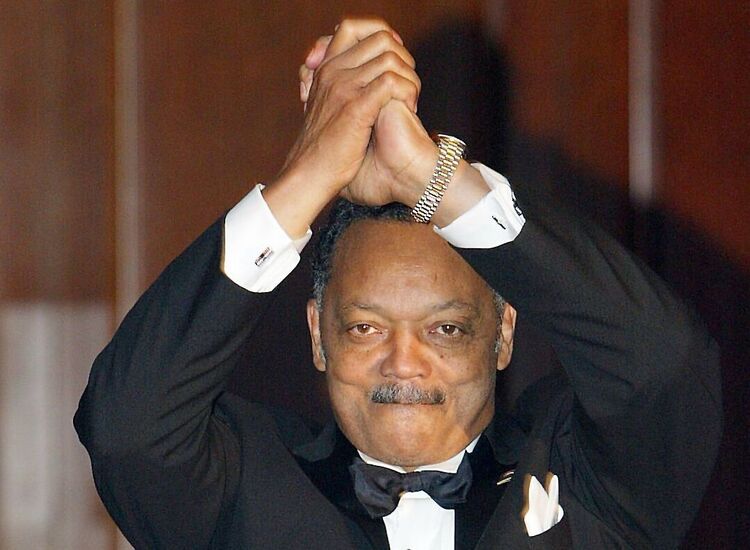

James Frecheville as Feeney. PHOTOS COURTESY OF IFC

Film Review / By Michael Gray

The people of Ireland can be justly proud of the achievements of their compatriots in the diverse fields of literature, drama, sports, and music over the course of the century that followed independence from Britain. But in the millennium between the victory of Ireland’s High King Brian Boru over the Vikings at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014 AD, and Ireland’s self-determination as a free nation in 1921, there is little to celebrate. The historic record of that time is a woeful litany of defeats and escalating oppression of language, faith and culture, punctuated by doomed uprisings that led, always, to bloody retribution for the rebel protagonists. The lowest of the low points in this sorry tale is, inarguably, the Great Famine of 1845-1849, a catastrophe that reduced Ireland’s population by a quarter from pre-Famine estimates of 8.2 million.

The failure of the potato crop over successive years caused the deaths of more than a million from starvation and fever, and triggered the departure overseas of a million more, starting a pattern of mass emigration that depleted the population to a low of 3.5 million a century later. This grim chapter of Ireland’s history has been well documented in print by the historians of the time and later, and remains a significant preoccupation for academics and fiction writers up to the present day. But the Famine has been a subject to avoid for filmmakers - until now.

Irish writer-director Lance Daly takes on this onerous task in his new fiction feature film, “Black 47”, training his lens on the Famine’s bleakest season: the harsh winter of 1847 that left the starving tenant farmers of the West of Ireland without their staple crop for the third year in a row, and facing a ruthless policy of mass eviction by their landlords.

Daly takes a daring approach to his unpalatable material – “Black 47” is framed as a revenge thriller that has more in common with the westerns of Sergio Leone than a typical historical drama. His main protagonist, Martin Feeney (James Frecheville) is a battle-weary soldier returning home to Connemara from service with the British army in India. Feeney is stunned to discover that while he was abroad, fighting for Crown and Empire, his mother had starved to death on the side of the road, and his brother was hanged for resisting the bailiffs when they evicted the family from their cottage and knocked it down. Smouldering with righteous fury, and with nothing left to lose, Feeney makes a hit list of those responsible for their deaths, and sets off on a murderous mission to dispense brutal justice to the rent collector, the land agent, the hanging judge and the landlord of the blighted estate on which the Feeneys rented their rocky acres.

Australian actor Frecheville, sporting a wild red beard and a fearsome, ice-cold stare that make him every inch the avenging Celtic warrior, give a riveting performance as the sullen, ruthless Feeney. His nemesis is an English ex-soldier named Hannah (played with matching grit by fellow Aussie Hugo Weaving), a veteran of the same regiment as Feeney, and an expert tracker of fugitives, who finds his loyalties to Queen and government conflicted by the hunt to apprehend his old comrade. The film is scripted in English and subtitled Irish, and Frecheville acquits himself admirably in the Connemara Gaelic dialect – even singing a song in the language, for Feeney’s surviving niece, in one of the few joyful scenes in an otherwise very dark film. The impressive cast includes Jim Broadbent as Lord Kilmichael, the pitiless landlord of the estate, Stephen Rea as a mischievous sleeveen who joins the hunt as a translator of the language Kilmichael dismisses as “aboriginal nonsense,” and Dubliner Barry Keoghan, playing a solider who snaps under the stress of guarding Kilmichael’s grain crop, destined for export before the very eyes of the starving farmers.

This harrowing journey across the bleak winter landscape of Connemara, beautifully shot by cinematographer Declan Quinn, makes for a gripping drama that defies genre conventions to convey raw historic truths. Expertly forged from inhospitable material, “Black 47” fully deserves to be seen by a wide audience. And it may be the only chance we ever get to see the recurring villains of the Famine narrative – the bailiff, the rent collector, and the landlord - getting their just desserts.

“Black 47” opens on this Friday, Sept. 28, for a limited run at IFC.