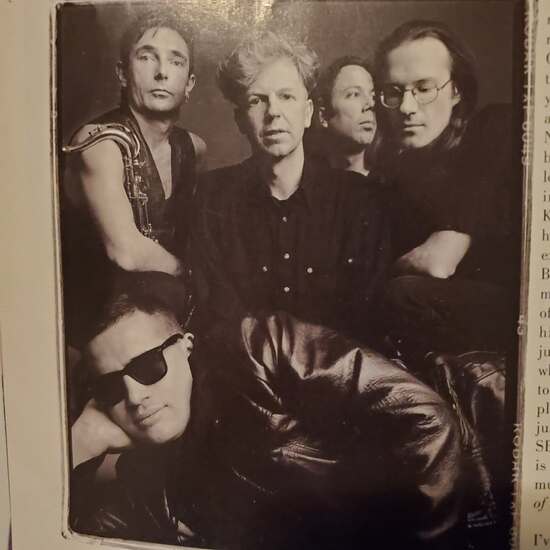

The author about to leave base for an air patrol in a helicopter

By Edward Hagan

On a sunny morning in late October 1969, my Sligo-born-and-raised mother walked me to the corner of Cooper and 204th Streets, where I got into a Datsun 510 for a ride to Kennedy Airport.

I had attended grade school, just two blocks north, at Good Shepherd School in Inwood, the northern tip of Manhattan. I was 22 and on my way to Vietnam.

My mother was fighting back tears that morning. It was deja-vu for her: in 1943 she had pushed my sister in a baby carriage down Cooper Street and put my Tyrone-born-and-raised father on the A train as he left Inwood for Europe.

He had been drafted at age 35, and, following the D-Day landing, his anti-aircraft battalion was sent to guard Cherbourg, a deep-water port in France.

In those decades, Inwood’s apartment houses were rented by the Irish although there were substantial numbers of Jews in the neighborhood. There were kosher butchers and, in 1969, 73 Irish bars north of Dyckman Street.

Gaelic Park was a short ride away on the #1 IRT/Seventh Avenue elevated train, across the Broadway Bridge into Marble Hill, and then into the Bronx. Everyone believed in God and loved the 196 acres of Inwood Hill Park, almost as much as Good Shepherd parish.

I recall Inwood frequently, and my year in Vietnam more frequently.

Virtually every draft-age Irish-American male I knew in Inwood made some sort of life decision about service in the war.

Many accepted the nation’s call to duty. My classmates at Good Shepherd School, Andy Garrity and Tommy Minogue, did not come home alive.

One day in February 1970 I got on a Huey helicopter in the Mekong Delta and soon discovered that the pilot was from Inwood. We were discussing Inwood’s bars on the intercom when the Viet Cong shot us down.

The war in Vietnam was a stalemate. That’s hardly news any more, but in 1969 Inwood staunchly supported its boys and, despite the 1968 Tet Offensive, believed in the light at the end of the tunnel - as long as traitors would stop flinching.

I remember receiving a tin of cookies from the patriotic boys and girls in the fourth grade at Good Shepherd. Chickie Donahue has recently published his epic story of a 1968 beer run from Doc Fiddler’s Bar in Inwood to neighborhood guys in Vietnam (“The Greatest Beer Run Ever,” Sugarwhistle, 2017). He ran into the Tet Offensive.

A year-and-a-half later, I became an intelligence advisor in the Mekong Delta and learned that our leaders, political and military, were supporting a corrupt government in Vietnam.

On the night before I left Inwood, I spent a few hours with my dear friend Rich Lundy in Uee’s Bar, on 207th Street between Vermilyea and Sherman Avenues.

We discussed all the important stuff like the Mets winning the World Series about a week earlier, and then we talked about all the friends who were gone.

Rich was a teacher and thus draft deferred, but Brendan Brophy was already in Vietnam. In 1967-68 Brendan, Rich, and Denis Hynes had played and sung together in an Irish ballad group the “Ragged Edges” in Uee’s along with Mary Powers.

Mary had reversed her parents’ emigration and had returned to Ireland. Denis had joined the Peace Corps and was in Dahomey (now Benin).

Actually the neighborhood was breaking up, but we didn’t know it then.

The 1965 Immigration Reform Act had turned off the faucet of Irish immigration, so there were no “Greenhorns” to replace us as we departed.

The Sixties for the Irish in Inwood had been glorious, full of hope. Bronx Irish Catholics crossed the 207th Street Bridge to go to the Old Shieling, Garry Owen’s, Chambers, the Inwood Lounge, and Sam’s. Marriages were made and hearts broken.

The young men became construction workers, cops and firemen; the young women became nurses at St. Vincent’s and St. Clare’s and secretaries at the Wood Secretarial School.

Every August and September, the whole world seemed to attend the St. Jude’s Bazaar on Tenth Avenue.

Kids went to summer day camps at Good Shepherd and St. Jude’s. Good Shepherd packed twelve Sunday Masses in the church, the chapel, and the school auditorium. The old men drank in the Lakes of Sligo, Good’s and Costello’s. Their wives shopped in the Grand Union on 207th Street, where, one day, “Candid Camera” filmed a segment of its show.

But hope was in trouble. JFK was shot in 1963 and LBJ was sending the boys off to Vietnam. Mike Morrow and Richie Reynolds died gallantly and came home for funerals out of Connor’s Funeral Home at 207th Street and Broadway.

I and many of my pals went to college. I went to Fordham, mostly for free, and my pals went there too. Other pals went to Manhattan and Iona. All of us knew that graduation meant a McNamara Fellowship in olive drab.

So I joined ROTC at Fordham and was sent to Vietnam as an advisor to the Vietnamese Popular and Regional Forces (called derisively and unfairly, the “Ruff-Puffs).

It hardly dawned on me that, at age 22, I had any advice for anyone, much less for my counterpart, a 35-year-old Vietnamese captain.

He was pretty smart. He didn’t ask me for advice. I had learned in Inwood to keep my mouth shut to stay out of trouble.

Advisors gained a perspective on the war that other American soldiers were shielded from.

I was part of a military and civilian advisory team that matched up with the South Vietnamese military and governmental organization of Phong Dinh Province in the Mekong Delta.

We were located in Can Tho, the largest city in the fertile delta. We engaged in a kind of “pretend war.” I worked in the province intelligence office where we kept estimates of enemy strength and filled out monthly reports of “progress.” I went out flying on missions on many afternoons and evenings and could read the ground without a map.

In my year there, we claimed to have killed 2,000 Viet Cong, but we estimated that there were 2,000 Viet Cong when I arrived - and there were still 2,000 Viet Cong when I left a year later. This was “fuzzy math.”

I wasn’t surprised when Saigon fell in 1975 and the house of cards called the Government of Vietnam crashed.

I’ve thought about Vietnam every day since.

I became an English professor, and now I teach great books about the war like Tim O’Brien’s “The Things They Carried” and Neil Sheehan’s “A Bright Shining Lie.”

O’Brien was an infantryman in Vietnam, and Sheehan covered the war for years, first for UPI and then, later, for The New York Times.

Yes, they’re both Irish Americans. When America gives a war, Irish Americans show up.

Of the 3,464 Medals of Honor awarded in all of America’s wars, an estimated 2,018 have been awarded to Irish-American recipients, more than twice the number awarded any other ethnic group. There are 81 soldiers named “Murphy,” the most common Irish name, on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

I’m especially fond of O’Brien’s “How to Tell a True War Story” with its wink at two meanings of “tell,” “say” and “recognize.” His narrator warns us: “If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or if you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie.” I’m fond of debunking Hollywood heroism, and my students seem to “get it.”

We’ve also been reading Seamus Heaney’s version of Sophocles’ ancient play, Philoctetes. Heaney named his version “The Cure at Troy.” The play focuses on the suffering of Philoctetes, who is abandoned on an island with a festering wound.

Odysseus put him there and rescued him only because Schemer Odysseus couldn’t win the Trojan War without Philoctetes’ famed bow.

The play has been produced for veterans in many venues recently. It illustrates the consequences of ostracizing the warrior from his community, an altogether too frequent situation that typified the treatment of returning Vietnam veterans, and continues up to the present.

Oh, yes, we’re very glib these days about “Thank you for your service,” but I wonder what would happen if the veteran said he’d like to tell his well-wisher just what he did in Iraq.

Try this one! See if the opening of this story makes you uncomfortable.

Phil Klay, a Regis High School alumnus and Iraq war veteran, begins the first story in his National Book Award-winning Redeployment: “We shot dogs. Not by accident. We did it on purpose, and we called it Operation Scooby.”

You might think that shooting dogs for fun is obscene, and it is: but don’t look away.

As O’Brien says: “If you don't care for obscenity, you don't care for the truth; if you don't care for the truth, watch how you vote. Send guys to war, they come home talking dirty.”

You might skip the formulaic bromide of “Thank you for your service” and actually talk to a vet. It’s too easy to say he doesn’t want to talk when you don’t want to hear. Neither of you is entitled to silence.

I decided a few years ago to get off the island and tell my war story. I tried not to lie.

Edward Hagan’s book “To Vietnam in Vain,” published by McFarland & Company, is available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble.com